Every day, hundreds of people walk, run, and bike along the Lafitte Greenway in New Orleans, one of the city’s newest parks. Bordering the central path are lush green bioswales — sunken gardens that capture stormwater. The 2.6-mile-long stretch of greenspace transects some of the city’s historic neighborhoods, connecting Bayou St. John to the French Quarter and passing through Treme and Mid-City along the way.

New Orleans-based architect Bryan C. Lee, Jr. calls the Lafitte Greenway “a civic green boulevard” and describes it as “a space that has continuous motion.”

This motion has certainly been present since the bike path was built in 2015, but the land beneath it has seen movement for more than 200 years. Before it was a park, it was a railroad, and before that, a shipping canal. Residents have always lived alongside this stretch of land. Lee sees a deeper story that needs to be told here. He envisions creating a new space — a bridge that will span the bioswales — that he hopes will encourage the park’s users to slow down, pause, and reflect on the city’s destructive, unjust, and buried history.

Lee is the founder and design principal for a nonprofit design and architecture firm called Colloqate (pronounced co-locate.) He approaches all of his work with a set of core beliefs he calls “design justice.”

“For every injustice in this world, there’s an architecture, a plan, a design that has been built to sustain that injustice,” Lee says. “We’ve got to acknowledge how, whether we play a minor role or a major role in some of these things, how best to not be complicit.”

Designing Justice

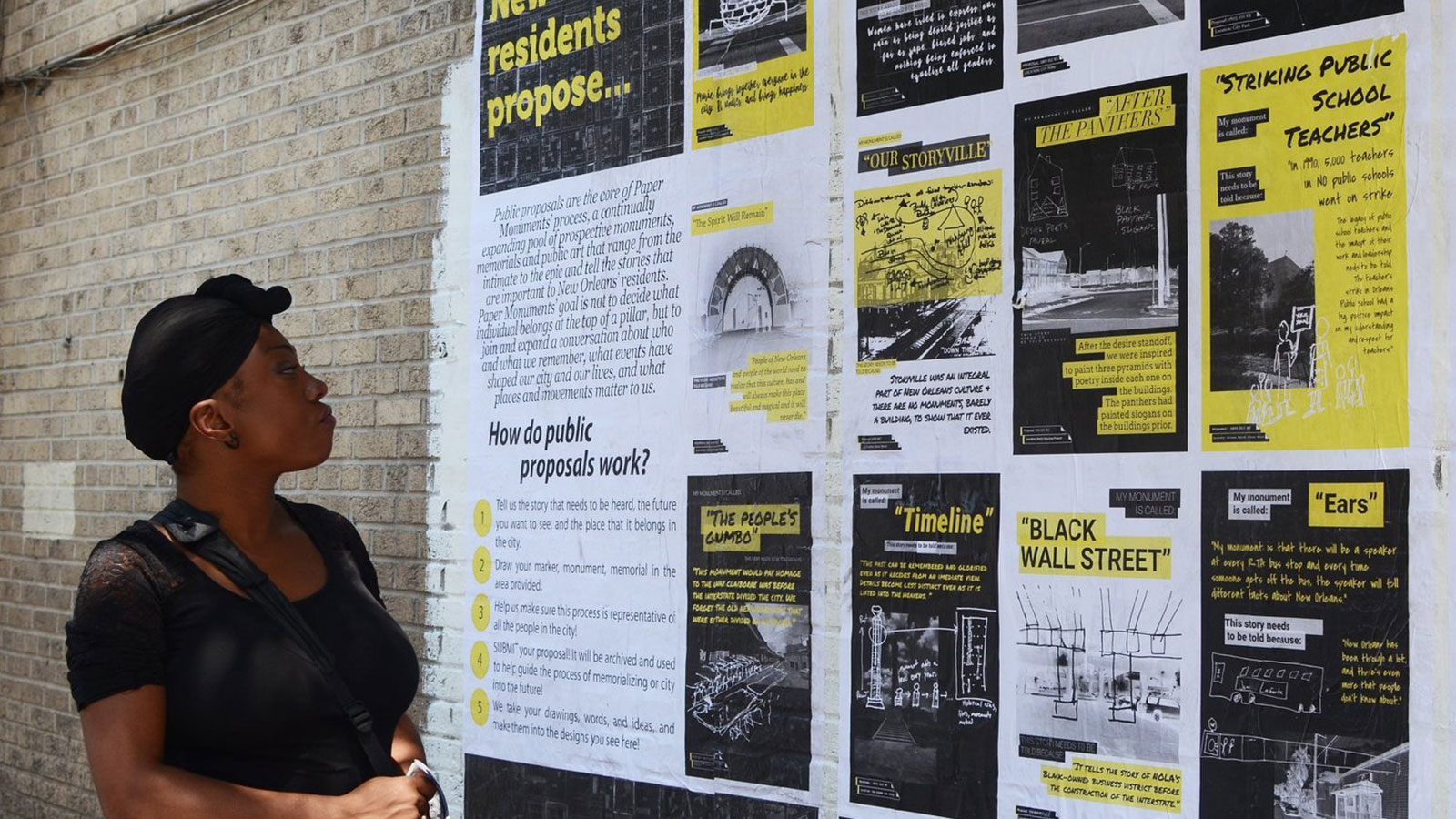

Lee and Colloqate first gained national recognition for a project they called Paper Monuments. In 2017, when Confederate monuments were being torn down across New Orleans, Lee and his colleagues collected a series of lesser-known stories about the city’s historical injustices. They created posters to tell those stories and pasted them on brick walls and public spaces across the city. The posters were also distributed at book stores and libraries.

In an open letter about the Paper Monuments, Lee and his colleagues said, “The question of a singular monument or of a singular location is less important than our conviction that all residents have a right to this city and an inherent role in shaping the place in which we all live, work, learn, and grow together.”

Now Lee wants to use architecture and design justice to tell a story about the displacement of people, cultures, communities, and environments across New Orleans. This time, his approach will be a series of outdoor pavilions he’s calling the Storia Program.

One will be a modified A-frame structure that opens up entirely and is planned for a site adjacent to the New Orleans African American Museum. As a venue for “collective memory” and storytelling, this “Defrag House” will be a hub for public art and also an event space for musicians and poetry readings. Lee’s aim is for it to represent the people and communities across New Orleans who have been forced out, whether by Hurricane Katrina, other impacts of climate change, gentrification, or violence.

“We are reflecting and building, essentially, a living memorial to those who have left and a living documentation of how that happened,” Lee says.

A History of Water and People

Another structure planned in the Storia Program is “the Delta”: A bridge spanning the bioswales of the Lafitte Greenway.

“It’s about ecological displacement,” Lee says. “The intention is to draw connections between our human movement around water and the city, and it’s movement around us. How has water influenced the city of New Orleans?” he asks. “How have we influenced the water systems within the city?”

The Chitimacha were the original inhabitants who lived on the land that is now New Orleans. Their homeland encompasses all of the wetlands in the Atchafalaya Basin in central Louisiana. According to their recorded history, the Chitimacha were one of the most powerful tribes in the southeast before European contact. Yet, a 12-year war with the French annihilated their members. When a Chitimacha chief signed a peace treaty in New Orleans in 1718 to end the war, the majority of their tribal members had been enslaved, killed, or displaced.

In the mid-1700s, the French transferred their authority to Spanish colonizers, who irrevocably transformed land and water to serve the powers of commerce and trade. During the final years of the 18th century, the governor of the then-Spanish colony, Francisco Luis Héctor de Carondelet, ordered forced laborers — convicts and slaves — to dredge a canal that would open up a new pathway for ships to access the heart of New Orleans. That canal is now the Lafitte Greenway.

In the mid-1800s, the canal was transformed into a railway corridor, and then in the late 1920s and early 1930s, part of it was filled. Eventually, the land fell into disuse and was abandoned. It sat like this for decades, until 2005, when a group of local residents — now called the Friends of Lafitte Greenway — saw its potential as a community park and started to advocate for its transformation. That same year, Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans and displaced hundreds of thousands more of its residents.

From the Chitimacha to Katrina, water has shaped the way people live in New Orleans. Lee wants the Delta bridge to span the centuries and tell these stories.

“It is fundamentally about how we tell a history of ecological and communal displacement, ecological and communal binding through this structure,” Lee says. “Both the structure itself and the habitat around it are nodes to a history and nodes to a story and place that is often negated and unfamiliar to residents.”

To address this ongoing historical inequity, Lee is working with New Orleans residents, including those who live in the homes adjacent to the park, to design the Delta bridge. He envisions it as a lightweight steel structure that stretches 60 feet in length and features pieces of art to speak to the ways in which water shapes land. But beyond that, he says the ideas and design will need to come from local residents.

To organize community around the Delta project, Lee wants to have conversations. He wants to ask nearby residents and the city at large about their experiences with water: How has water shaped their lives? How has the environment and climate change influenced them specifically? But Colloqate is not just distributing questionnaires or handing out surveys in order to collect data. Their aim is deeper: to listen to stories and build relationships.

“Humans are directly related to the outcomes that we put into the world,” Lee says. Engaging with people is just as important to a project as the structure itself.

Architecture for Community Power

At Colloqate, architecture is not simply a profession of designing buildings and structures. Lee and his colleagues firmly believe that the very premise of architecture is complicit in systems of racism by creating physical environments that have historically disenfranchised Black and Brown communities, blocked people from accessing power, and reinforced segregation.

“Design justice is actively about challenging existing systems that use architecture as a tool of oppression,” Lee says. It seeks to tear down those structures and rebuild them with intention to give communities power.

When applied to outdoor spaces, he says design justice, along with art, can expose buried histories in the landscape. Public spaces present an opportunity to build community and host civic engagement. Beyond that, design justice also begs the question of what a park means, as a concept and a cultural value, to different communities.

“When we talk about parks, are we still talking about it through a lens of whiteness or are we doing it through a lens of Indigeneity or Blackness or Hispanic, Latino? How are we seeing it?” Lee says. “If we are capable of reconciling cultural differences and building spaces and places that support a larger swath of engagement, we’re going to do a lot better.” He goes on to say, “It’s harder to detangle and dismantle communities when communities are whole, when they have connections to one another.”

In a part of the city that’s seen so much movement for centuries, Lee hopes the Delta bridge will offer people a place to pause and think, perhaps about their relationship to the history and context of the place.

With the pandemic, community organizing around the Delta project and others has largely been put on hold. Lee now hopes the bridge and the Defrag House will be built in early 2021.

“Our ability to really pull people together in this moment is tough,” Lee says. But public outdoor spaces are taking on new meaning and importance in light of public health guidelines for COVID-19. One could argue that design justice is more important now than ever. “The sole purpose,” Lee says, “is to build power and build community.”