What more is there to say about a man who wrote three autobiographies, has been profiled in virtually every magazine (from the New Yorker on down), and was interviewed on every television and radio show worth its salt?

David Brower, 1912-2000.

Photo: Earthjustice Legal Defense Fund.

I speak of David Brower, my friend and idol for a lifetime, who died Sunday in Berkeley, Calif., at the age of 88.

During the Christmas holidays in 1964, the Browers were at my parents’ for an annual Tom and Jerry party. Dave and I were chatting, about what I don’t remember. He said, “Wait a minute. You have a very good speaking voice. Would you be willing to narrate a slide film for the Sierra Club?” I was 22, about to graduate from college, and flabbergasted. “Sure,” I said, and my life has never been quite the same.

The film had to do with Glen Canyon, the extraordinary sandstone complex in southern Utah carved by the Colorado River — and at that time slowly disappearing beneath the rising waters of Lake Powell. The Sierra Club was making the film to rally the public to ensure that the same fate not befall the Grand Canyon, as was then being proposed in Washington. I recorded a soundtrack for the film, then finished school in January. Over Easter break, my family joined the Browers and about 20 other people on a farewell visit to what was left of Glen, the canyons of the Escalante River, including the stupendous Cathedral in the Desert. To see up close what was about to be drowned forever was an experience that still brings tears to my eyes and fury to my soul.

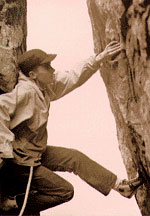

Brower in 1934, climbing in Pinnacles National Monument.

Photo: Earth Island Institute.

I joined the Peace Corps soon thereafter, and when I returned from abroad, I stumbled into a job at the Sierra Club, editing the papers of the legendary mountaineer Norman Clyde into a book-length manuscript. This was in the spring of 1968, when the storm clouds were beginning to swirl around Dave, and his relations with a part of the Sierra Club’s board were heading irretrievably downhill. A year later the verdict was in and Dave was forced to resign — to walk the plank, as he would frequently characterize it. I, for my modest troubles, was sacked.

We repaired to an office on the ground floor of an old firehouse in San Francisco, downstairs from the ad man Howard Gossage, who had conspired with Dave to produce the newspaper ads largely credited with defeating the Grand Canyon dams. In his resignation speech to the club, Dave had announced the formation of an as-yet-unnamed organization to take up where the club had forced him to leave off. (One of the many things that had gotten Dave into hot water at the Sierra Club was trying to involve the group in international activities.) We settled on the name Friends of the Earth. That organization grew and attracted independent affiliates abroad, in more than 60 countries at this writing. I worked for Dave there for 17 years, until the FoE board, over Dave’s militant objections, voted to close the San Francisco office, lay us all off, and regroup in Washington, D.C. I went on to the Sierra Club Legal Defense Fund, while Dave and several others set out to turn Earth Island Institute into a vibrant, vigorous organization.

Dave was many things, as has been chronicled elsewhere, many times over. Mountaineer, writer, photographer, editor, visionary, sound-bite genius, mesmerizing speaker. I learned all I know about thinking clearly, writing, editing, asking good questions, being skeptical, and sticking with a job from Dave. He was forever quoting people to make his points, so maybe I’ll just quote him, the tribute he paid Rachel Carson upon her death: “She did her homework, she minded her English, and she cared.”

This sentiment also fits Dave perfectly. No one cared more.

I miss you, Dave Brower; we all miss you. Thank you for all you did for us, and for the earth.