For the Pentagon, there’s no denying that climate change is a real, urgent threat. Never mind who’s sitting in the White House. But this arm of the government tasked with protecting the country from threats is actually making this one worse.

The Department of Defense spews so much greenhouse gas every year that it would rank as the 55th worst polluter in the world if it were a country, beating out Sweden, Denmark, and Portugal, according to a new paper from Brown University’s Costs of War project.

The irony is that the military is concerned about what will happen as the world keeps heating up. Last year, the Department of Defense reported that half of its bases were threatened by the effects of global warming. Rising seas are regularly flooding Norfolk Naval Base in Virginia, even on sunny days, and melting permafrost threatens the stability of military buildings in the Arctic.

On top of that, national security experts project that climate change will fuel more conflicts as resources become scarce. They suggest that the drought in Syria, for example, helped create the conditions for the civil war that started there in 2011.

“However, the Pentagon does not acknowledge that its own fuel use is a part of the problem or that reductions in Pentagon fuel use are a potentially significant way to reduce the risks of climate caused national security risks,” writes Neta C. Crawford, a professor of political science at Boston University, in the report.

The U.S. military emitted a whopping 1.2 billion metric tons of CO2 between 2001 (when it invaded Afghanistan) and 2017, according to the report’s estimates. That’s about as much as all of Japan emits in one year.

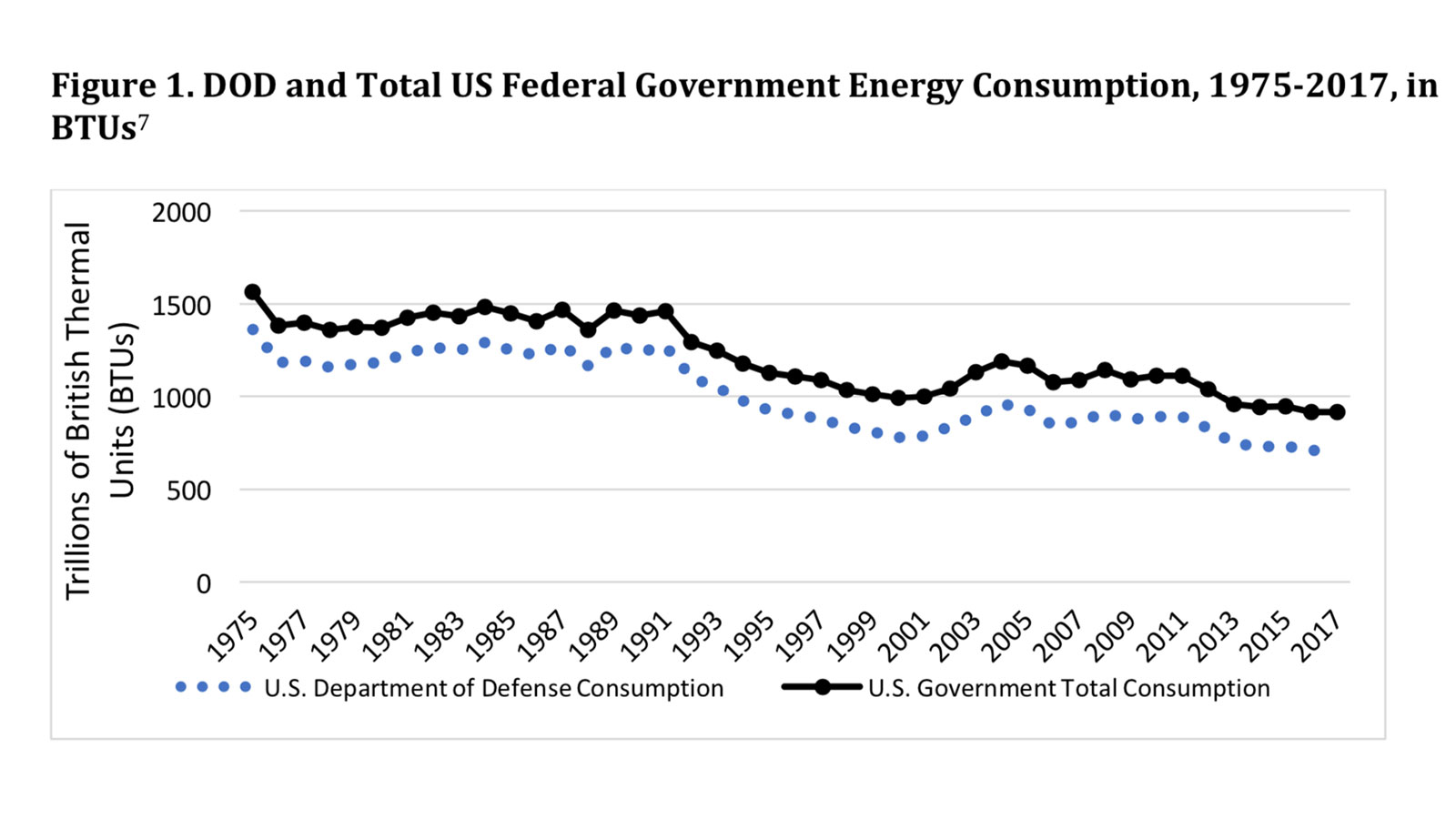

Since the Pentagon doesn’t report how much fuel it’s using to Congress, Crawford used Department of Energy data for her calculations. She found that it consistently makes up 77 to 80 percent of the entire U.S. government’s greenhouse gas emissions.

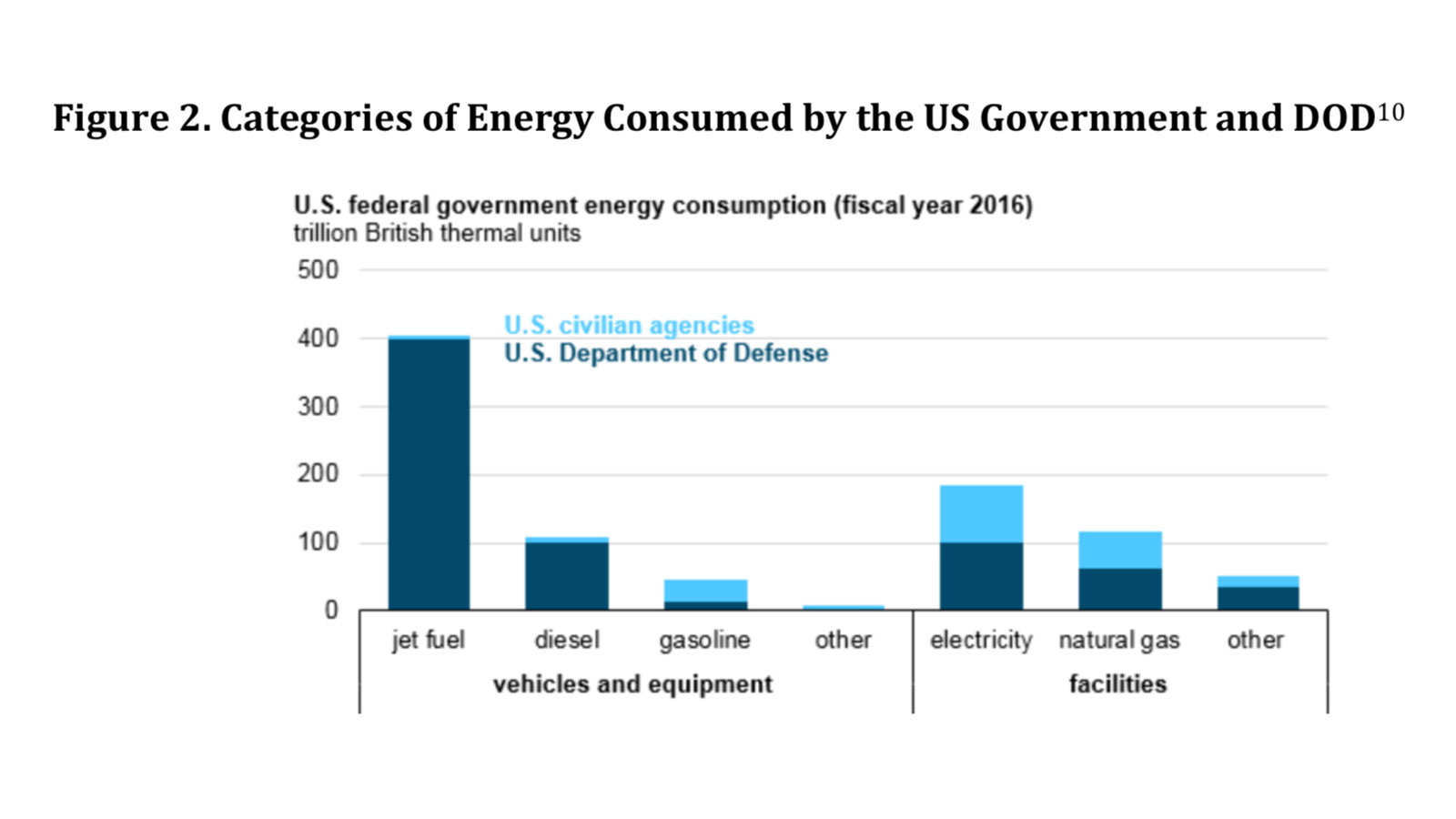

Why so much? Well, first off, there’s all those military buildings (some 560,000 on bases around the world) to power, heat, and cool. That accounts for about 40 percent of the total. The rest goes toward operations like moving troops and carrying out missions. The biggest CO2 culprit is, by far, planes. “Aircraft are extremely thirsty,” Crawford said.

Neta C. Crawford, Costs of War Project, Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs, Brown University

Diesel fuel is another biggie. Fun fact: The military’s fleet of Humvees get around 4 to 8 miles per gallon.

That said, the military has been gradually reducing its oversized carbon footprint, even while it wages war in the Middle East. Over the last decade, the Pentagon has been investing in renewables like solar, weatherizing buildings, and cutting down on the time planes sit idle on runways. Still, it’s got a long way to go.

Neta C. Crawford, Costs of War Project, Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs, Brown University

The weird thing is that the military is essentially burning oil … to protect access to cheap oil. “It became the mission to protect Persian Gulf oil in 1979,” Crawford said, and there’s really been no change in the military’s overall strategy since.

If the Pentagon finds ways to run more on renewables and reduces the amount of oil it uses, she explained, then it could direct fewer resources to protecting oil, thus further cutting down on emissions. See how that virtuous cycle works?

The military’s carbon footprint has already made its appearance in the presidential race. Senator Elizabeth Warren from Massachusetts, one of many hopefuls for the Democratic nomination, recently detailed an ambitious plan requiring the Pentagon to reach net-zero carbon emissions on non-combat bases and infrastructure by 2030. She wants to invest billions in Defense Department research on microgrids and advanced energy storage.

Crawford has other ideas for reducing emissions. The first is cutting military spending, which accounts for more than half of the government’s discretionary budget. At around $600 billion a year and climbing, it’s more than what the next seven largest countries spend added together. And that’s not including billions and billions for related expenses. If the military was to downsize its bases, or close the ones already flooding regularly, that land could be put toward solar and wind production or planting trees that suck up carbon, Crawford said.

Instead of just reacting to climate change and preparing for the worst, the Pentagon has the opportunity to make the worst less likely to happen.