Alston wants your women.

And not just any old hags, either — residents of this northern English town would prefer strapping young things who aren’t afraid to get dirty. “Quite frankly, old people are not going to give us the vitality that we need,” says Vince Peart, the cheerful if lovelorn spokesperson for the town’s matchmaking campaign. “We’re looking for young people who will work.”

The area around Alston, a hamlet perched in the Pennine mountains, was once home to 20,000 people. Nowadays it’s closer to 2,000. While Peart’s booty call has proved to be a headline-grabbing move, he admits it’s not just women the town is lacking. Warm bodies of all sorts are in short supply.

Peart is trying to keep positive as he crisscrosses Britain on a double-headed mission to lobby politicians on rural issues and get dates for his buddies. He and other lonely Alstonites should take heart, though: they’re really not alone. Around the world, a demographic shift is under way, with people having fewer children. The resulting population decrease could — more than hybrid cars or wind farms or policy shifts — be our best hope for the salvation of the planet. Eventually.

Less Is More, More or Less

The little attention given to shrinking populations tends to focus on Europe. Among the nations with the lowest fertility levels in the world are relatively rich countries like Italy and Spain, but they are matched by still-developing Eastern European nations like Romania and Ukraine. Even the continent’s comparatively lusty countries, such as France and Ireland, are only cranking out an average of 1.8 children per woman — well below the “replacement level” of 2.1 that’s needed to sustain current population levels.

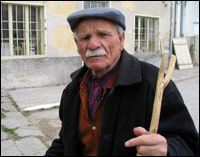

Last of a dying breed?

Photo: iStockphoto.

Populations are declining in seven of the 25 European Union member countries, and the trend will continue. According to Eurostat [PDF], the E.U.’s pocket-protector brigade, population numbers will rise gradually over the next two decades to about 470 million, thanks mainly to immigration, before falling by 20 million people by mid-century, when immigration will no longer be able to offset rising death rates and falling birthrates. Germany alone is projected to lose 8 million by 2050, a drop of nearly 10 percent from its present population of 82.5 million — that’s a loss roughly equal to the populations of its five biggest cities combined.

This trend isn’t brand-new; in fact, Oxford demographer David Coleman dates declining birthrates in Europe to the social-welfare state that began in the 1930s. In a society veering away from agriculture, he points out, children were no longer worth it, in hard economic terms. Other explanations for falling birthrates include women’s rights, increasing female participation in the workforce, and birth-control programs.

Outside Europe, a notable trend toward depopulation is also occurring in Japan, where the fertility rate has fallen in recent years. The government estimates that by 2050 there will be 25 million fewer Japanese — that’s like saying goodbye to one-fifth of the current population, or all of greater Tokyo.

But the real surprise may be that birthrates are falling even in developing nations. Throughout the developing world, the U.N. says, people are having fewer babies — an average of fewer than three per woman — and 20 developing countries have fertility levels below the 2.1 replacement level. China’s policies, including the notorious one-child rule, have driven its birthrate from 5.9 in the 1970s to sub-replacement level. An even larger decrease — the fastest ever recorded — occurred in Iran, which dropped from seven births per woman in the early ’80s to around the replacement level today.

So is this good news for those concerned about crowding and consumption? Well, here’s where it gets a bit tricky. Even though birthrates are falling, we’re decades away from feeling the effects. According to the U.N.’s best guess, anyone still kicking in 50 years will be sharing the world with about 9 billion others. Even where birthrates are below replacement level, populations continue to grow — there’s a time lag before the effects of declining birthrates are felt. For instance, one estimate projects that China will still add 260 million people by 2025.

Business as usual in Tokyo.

Photo: iStockphoto.

Immigration and urbanization also create a sort of demographic microwave, leaving some areas ice cold and others blisteringly hot. In much of Europe and Japan, while rural areas are emptying out and birthrates are plunging, cities are coping with an influx of newcomers. For every amusing feature about a town like Alston, there’s a corresponding news flash about thousands of Eastern Europeans moving to the U.K. In Rome, squatters are angry about spiraling housing costs caused by overcrowding. Meanwhile, in the former East Germany, where a sagging economy and the ease of migration to the West are compounding downward population trends, they’re chopping up old communist apartment blocks to make nice low-density family homes — that is, if concrete can ever be considered either nice or low-density.

But still, the big picture is getting smaller. After 2050, the U.N.’s medium-scenario estimates say the world will grow more slowly, hitting a peak of about 10 billion people in 2200 before stabilizing or entering a period of slow decline. This involves a huge amount of guesswork — we’re talking about estimating the number of children born to parents who aren’t yet born themselves — but the ultra-long-term trends are down.

Crave New World

This may be bad news if you sell cradles or run a mommy podcast, but environmentalists could have cause for celebration. In Europe, some of the effects are already being felt. “The decline in population is opening room for species that have been pushed back by humans,” says Reiner Klingholz of the Berlin Institute for Population Development. “We’re seeing an increase in animals such as wolves and deer.

“In [eastern] Germany, for example, you have old buildings, houses, factories, railway lines, and so forth where nature has taken over,” he adds. “In places where there was nothing but humans and industry, now you have birds nesting in the rafters and foxes lurking around.”

And fewer people could also benefit — well, people. Oxford environmentalist and population expert Norman Myers says a smaller population is a more sustainable one. A drop in numbers could lead to a drop in energy use — think fewer cars on the road, fewer power plants, smaller towns — which bodes well for the climate. “This is something to be applauded solely because the sooner we move to declining populations, the less strain we place on the environment,” Myers says, “and the better off we’ll be.”

But let’s put the champagne and condoms on ice for a moment. Shifting populations bring their own set of concerns. For instance, Europe’s population is still rising — but four-fifths of that increase is due to immigration. Since new arrivals tend to be shunted into low-wage jobs, some demographers warn that European societies could fissure into two castes: childless Brahmins and the foreign underclasses who serve coffee, sweep streets, and shell out taxes to support them.

Gray matters.

Photo: iStockphoto.

On top of that, a declining population is an aging one. And in an aging society, says Philip Longman, a senior fellow at the New America Foundation and author of The Empty Cradle: How Falling Birthrates Threaten World Prosperity and What to Do About It, “gray competes with green.” Older people tend to have more disposable income, and thus tend to consume more. They use more housing units per person than families, swelling their environmental footprint. And ultimately, says Longman, “aging societies will face budgetary pressures” — think Social Security and other pension plans — “that will leave less resources available for investment in cleaner energy, conservation, remediation, mass transit, and all other environmentally friendly goods.”

Could the environmental dream of zero population growth be a nightmare? Some think so. I ask Vince Peart if he sees any benefit to undercrowding. He thinks for a moment — long enough for a few Alston old-timers to drop off — but can’t come up with an answer. There aren’t more trees around or more native species to admire in his town. Perversely, the cost of living is going up as city people snap up second homes in the area. And the weekenders don’t tend to support local businesses. Finally, he just says, “We’re at risk of turning into something of a ghost town, a tourist attraction.”

The Incredible Shrinking Debate

With the global population zooming upward, it’s hard to drum up much talk about future depopulation. And even those you might expect to be excited at the prospect aren’t talking about it much, because advocating smaller populations isn’t very … sexy. Groups like Greenpeace and Oxfam, which once championed population control, now barely mention it, according to David Nicholson-Lord of the Optimum Population Trust. He says progressives haven’t been able to blend commitments to reproductive choice with sustainability, so raising the banner for population control has been left up to a few lonely voices on the left and, on the other end of the spectrum, the anti-immigration right.

“I think [population control] is deeply unfashionable, and taboo, and has fallen off of a lot of agendas — and that’s due partly to that broad agenda known as political correctness,” Nicholson-Lord says. “It’s seen as the wrong diagnosis and also as disempowering … it has a bad name, and unfairly, I think.”

Nicholson-Lord and his trust embrace positions that would make most liberals queasy, like zero net immigration for the U.K. He argues that more groups should concern themselves with such issues, since the environmental benefits of a lower population are just too high — and the world’s environmental problems too urgent — to push for anything less. “We have to think seriously about the world’s population,” he says, “and about what kind of levels can be sustained in the long term.”

If anybody running Europe is doing this type of pondering, they’re not saying. In the playground of public policy, population decrease is seen as a problem, not an opportunity. Several countries, including France and Estonia, offer generous pro-family benefits, while others, including Britain, Italy, Belgium, and Germany, are tinkering with their retirement systems to keep older residents working longer. But in debates over pensions and child and family benefits, serious discussion about proper population levels doesn’t really happen.

And there’s the challenge. The issue of population, once a key part of the green agenda, is today limited to a few demographers, think-tankers, and wonks. If countries can manage with fewer people, and even turn depopulation into an environmental benefit, we could be onto something big. Political tussles over whether to cut emissions or pursue clean technologies might seem as quaint and empty as a pub in Alston. But before that happens, we’ll have to start talking about it again.