HBO is done with Game of Thrones — finally!!! Don’t @ me! — which means we can all get back to focusing on the network’s best show: Big Little Lies. The sunlit, seaside drama is now in its second season, and in its latest episode, it brings an unexpected topic center stage in a surprisingly nuanced way: climate change.

If you haven’t seen it, here’s what you need to know about the series. It’s set in Monterey, California, a picturesque, dumb-rich town perched over the Pacific Ocean. It’s home to a privileged, mostly white, and unabashedly duplicitous community of parents — kind of like The O.C. but with grown-ups, better writing, and pinot noir instead of vodka shots.

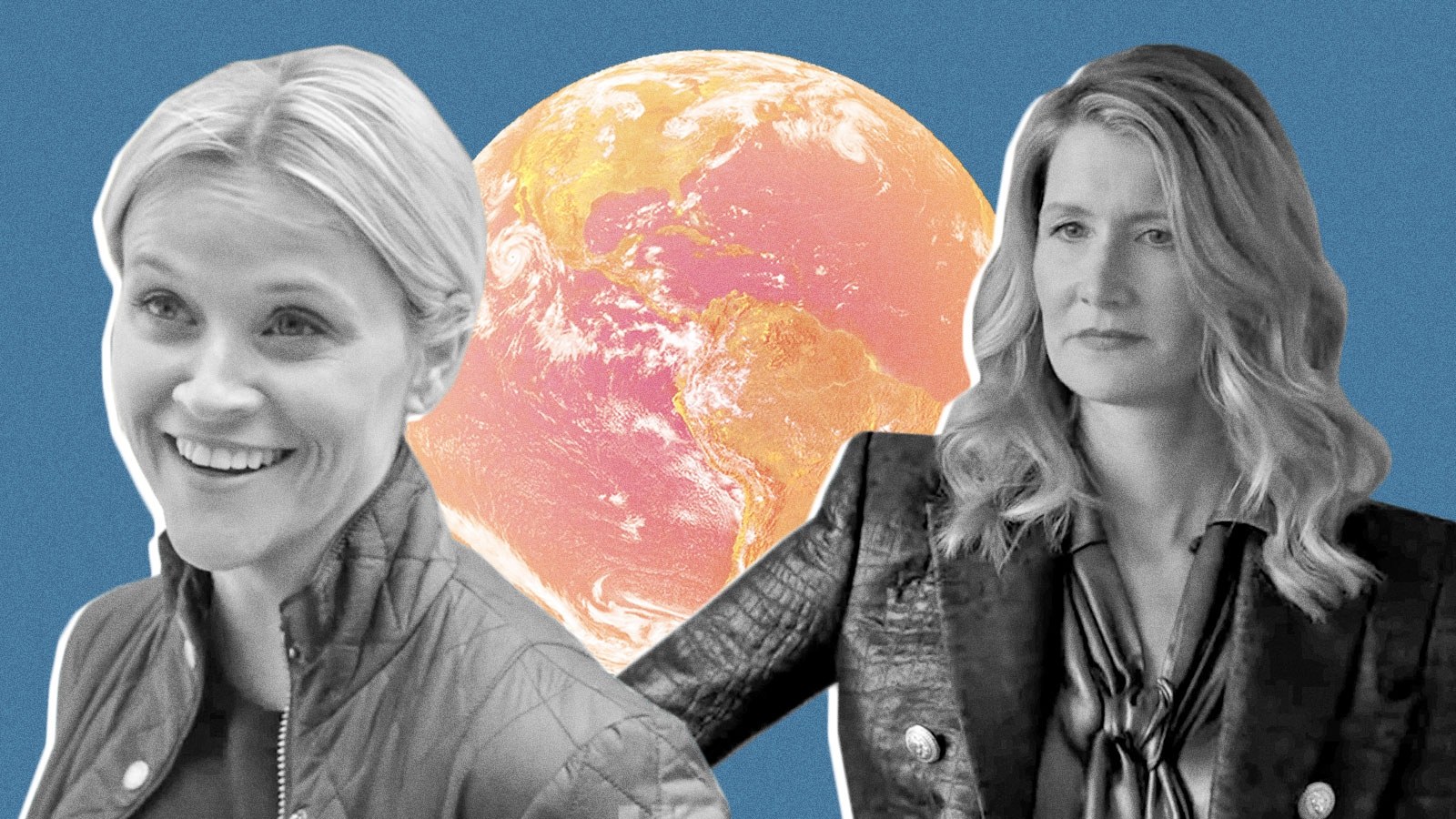

An ongoing thread of the show is the age-old phenomenon of mothers both projecting their worst fears onto their children and trying to protect them from those very fears. That plays out in the most recent episode where the high-powered, hyper-neurotic Renata (played by Laura Dern) and the impetuous Madeline (played by Reese Witherspoon) unpack a particularly controversial lesson about climate change.

Mr. Perkins (Mo McRae), who teaches Renata and Madeline’s second-graders, leads the class in a discussion of Charlotte’s Web that introduces the idea of environmental responsibility and environmental collapse. While he never actually says the words “climate change,” the scene ends with Amabella, Renata’s daughter, having a panic attack. We later find out (via a child psychologist dressed as Little Bo Peep) that her strong reaction is the result of anxiety brought on by learning about climate change in the classroom, no matter how obliquely.

In true Renata fashion, she meets the teacher and principal with guns a-blazing. “What possesses two idiots like yourselves to teach 8-year-olds that the planet is doomed?” she demands. Mr. Perkins attempts to explain that it’s his job to help “deconstruct” climate change so the kids can process it, but Renata leaves with one last note. “I will buy a fucking polar bear for every kid in this school.” (Side note: polar bears are no longer the symbol of climate change. Sorry, Renata!)

But an intriguing — and current — question sticks at the heart of the episode’s conflict: How do we explain the impacts of climate change to children?

A recent NPR poll found that 80 percent of parents wished their kids would get information about climate change in the classroom. The vast majority (86 percent of teachers) agreed that they’d like to address the topic, but only around 45 percent said they actually did so. The most common response for why they weren’t teaching it? They felt it was “outside of their subject area.”

But Big Little Lies is all about conflict and ~drama~, so of course it centers around opposing approaches to addressing climate in the classroom.

The Renata camp would argue that second-graders are too young to manage the kind of anxiety that naturally results from a conversation about the end of the world. She argues that kids don’t have the skills they need to process what 2 degrees C of warming actually means for the planet and ultimately for their future. Anxiety in children is already at an all-time high, so why should teachers add to that stress by weaving the disasters of the future into the day-to-day of their present? How can we expect them to take action on climate change if they can barely tie their shoes? And who would blame a parent that wants to protect their children from the scariest of realities?

The Madeline camp argues that yeah, climate change is scary, but it’s the scary truth.

The conflict peaks in the auditorium of Otter Bay Elementary School, where the administration has gathered parents to discuss their reactions to including climate change in the curriculum. Madeline takes the stage in what seems to be the start of another rant against climate change in the classroom, but evolves into a candid confrontation of the lies parents tell their kids, and ultimately themselves.

“I think part of the problem is we lie to our kids,” Madeline says. “We fill their heads full of Santa Claus and stories with happy endings when most of us know that most endings to most stories fucking suck.”

The other parents, including Renata, seem shocked by Madeline’s candor and cringe at the sting of an accurate assessment of the Monterey parent-child dynamic.

The overarching theme of Big Little Lies is the falsehoods we tell to protect ourselves and others. Often, we lie to soothe ourselves and to avoid upsetting or difficult realities. And gradually, little self-reassuring lies — no one actually recycles, so why should I? — compound into bigger lies — climate change isn’t a big deal! What better way to describe how modern society has reached the point of climate disaster?

Most of the time, confronting the reality of climate change can feel daunting. The whole world is suddenly facing collapse on a scale that humans have never experienced. So when we think about communicating something that’s hard for adults to process to our kids, where do we even begin?

Madeline doesn’t answer that question, but essentially proposes that adults try to talk to their kids about climate change anyway. She goes on to say: “We tell them things like, ‘You’re fine, you’re going to be fine.’ And we tell ourselves we’re gonna be fine, but we’re not…You can’t tell them part of the truth. You have to tell them the whole truth.”

Renata’s and Madeline’s impassioned reactions to Otter Bay’s second-grade curriculum reflect the state of their chaotic personal lives. Renata is protective to the point of deranged, a reflection of her stress over losing the family fortune and the stability she worked hard to attain due to her husband’s financial mishaps. Madeline, having already lost everything as a result of an affair, has essentially run out of fucks. They’re each projecting their personal situation onto the climate crisis, which is a pretty common tactic.

I don’t think Madeline’s argument is to drop the whole arsenal of truth bombs on second-graders. But her point of not concealing the truth in the name of protection is valid. Kids are intuitive and curious; they have questions that require thoughtful, honest answers that are often complex. But conveying that complexity to kids without sending them into a panic attack is the challenging part. For advice on that, I turned to my 8-year-old sister and doppelgänger, Lily.

“Adults shouldn’t be like, ahhguhhhahh!!” she said. Rather, our explanation of the planet’s woes should be delivered calmly. She advised parents: “Say ‘We can change the future if we do this and this.’ If they say it calmly instead of acting like it’s something that we can’t change, then we learn to do what we can.”

I asked the same thing of my dad, who has worked in elementary education for almost 30 years — and, you know, is raising a second-grader at a time of climate crisis. “Kids are smart,” he said. “As teachers, it’s our job to answer their questions in an appropriate, truthful, and honest way.”

But I think I should let Lily have the last word:

“You should feel scared because it’s a scary thing,” she added. “But if we helped, it could be less scary.”