This is the second in a series; the first is here.

We’ve covered two reasons Environmental Defense is pushing for passage of climate legislation in 2008 — the politics will be very much the same in 2009, and we don’t want to gamble away a good bill on the chance of a perfect one someday.

Today I’ll look at a third reason: The price of waiting, even a year or two, is simply too high. Carbon dioxide concentrations are higher today than they’ve been in 650,000 years, and our emissions rate is increasing. It’s crucial that we start aggressively cutting emissions as soon as possible.

Here’s the math.

Source: the national allowance account for the years 2012-2020 from the S.2191 as reported out of the EPW Committee. The emissions growth from 2005 to 2013 is assumed to be 1.1 percent (an average of the 2004 and 2005 rate reported by the EPA [PDF]).

Scenario one: The Climate Security Act is passed into law this year, and takes effect in 2012. To comply with the emissions cap, covered sources would have to cut annual emissions by roughly 2 percent per year. By 2020, they would be emitting at 15 percent below the starting point in 2012.

Scenario two: We delay enacting legislation by two years, holding everything else constant. We pass a cap-and-trade bill in 2010, and it takes effect in 2014. To meet the same cumulative emissions cuts, emissions would have to fall by 4.3 percent per year — over twice as quickly — and we’d have to do it year after year until 2020, just to get to the same place. By 2020, emissions from covered sources would have to be cut 23 percent below the starting point in 2014.

Why is there a four-year gap between when the bill is enacted and when it’s implemented? It’s to allow time for the Environmental Protection Agency to get its rule-making done — a massive effort — and to give regulated industry formal notice of required changes. Passage of legislation will affect all manner of planning and action, including new accounting systems and more. The country can’t turn on a dime. It takes time to implement this level of change.

If a bill legislating mandatory caps is enacted later, odds are it will be implemented later, and deeper cuts will be required.

Inaction is the most expensive option

Deeper cuts mean a deeper impact on our economy. Study after study shows that inaction is the most expensive option:

- A recent report by the University of Maryland found that "negative climate impacts will outweigh benefits for most sectors that provide essential goods and services to society." For example, "New York State’s agricultural yield may be reduced by as much as 40 percent, resulting in $1.2 billion in annual damages."

- A more detailed study of Florida reached similar conclusions. Economic damage to just three sectors — tourism, electric utilities, and real estate — combined with hurricane damage would shrink the state’s gross domestic product by more than 5 percent by the end of this century.

- A study by McKinsey & Company also warns about the high cost of delay. Greenhouse-gas abatement can be highly affordable, but won’t remain so forever. From the executive summary: “Many of the most economically attractive abatement options we analyzed are ‘time perishable’: every year we delay producing energy-efficient commercial buildings, houses, motor vehicles, and so forth, the more negative-cost options we lose.”

The science is unforgiving

As the Earth warms, we approach a “tipping point” of no return, after which large destructive changes become inevitable. The most immediate potential catastrophe is the melting of the Greenland ice sheet, which would cause a drastic rise in sea levels. Scientists estimate this could occur when temperatures reach 2°C above pre-industrial times.

If we pass the tipping point, economic and social costs will be astronomical. How much will it cost to deal with a 20-foot rise in sea levels that puts Wall Street under water? Oceans won’t rise this high immediately, but the tipping point — the point after which it’s inevitable — is close at hand. Once we pass the tipping point, it’s just a matter of time. We may not see the worst of the damage in our lifetimes, but our descendants will.

Who wants to play chicken with the Greenland ice sheet? We’re pushing for a bill now.

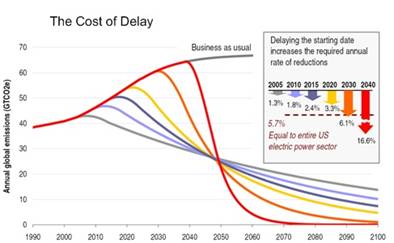

The cost of delay

The long-term target in the Lieberman-Warner Climate Security Act is not at the level that the best science recommends, but its near-term cap is aggressive — more aggressive than any other proposal currently filed with Congress.

As I wrote earlier, long-term targets aren’t etched in stone. We have time to make them stronger. But short-term targets are critical because the science is unforgiving. The longer we wait to get started, the deeper the cuts must be to avoid environmental catastrophe.

Source: Environmental Defense analysis using the MAGICC climate model.

The worst thing we can do for our economy and our environment is to pass no legislation at all. The second worst thing we can do is delay — by even two years. If we start now and decrease emissions slowly, we can minimize the pain of shifting to a low-carbon economy. If we delay, we won’t have the luxury of gradual change. And at some point, if we continue to delay, it will become impossible to cut emissions quickly enough to avoid the tipping point.

Stay tuned for my next post, which will discuss why the importance of America’s role in international negotiations toward a successor to the Kyoto Protocol makes it more important than ever that we pass a bill this year.