Dear Umbra,

Why do you think people litter, and what is the best way to discourage littering in one’s community when there is wide economic disparity?

— Taking Responsibility Around Scraps, Honorably

Dear TRASH,

I get the sense that you’re writing from or about a gentrifying neighborhood, a rich source of tensions in Umbra’s mailbox. And litter itself is such a deeply complex salad of environmental issues!

We can begin with the obvious: the fact that we wouldn’t have so much litter without the production of so many single-use items that need to be disposed of. According to the nonprofit Keep America Beautiful, roadside litter decreased by 61 percent between 1969 and 2009, while the use of plastic packaging increased more than threefold — and accordingly, plastic litter increased by 165 percent. But there’s a plot twist! Keep America Beautiful, which is kind of the national authority on litter, was originally founded by packaging companies in the 1950s to frame waste as an issue of personal rather than corporate responsibility. So that’s the systemic background against which all personal trash-disposal choices take place.

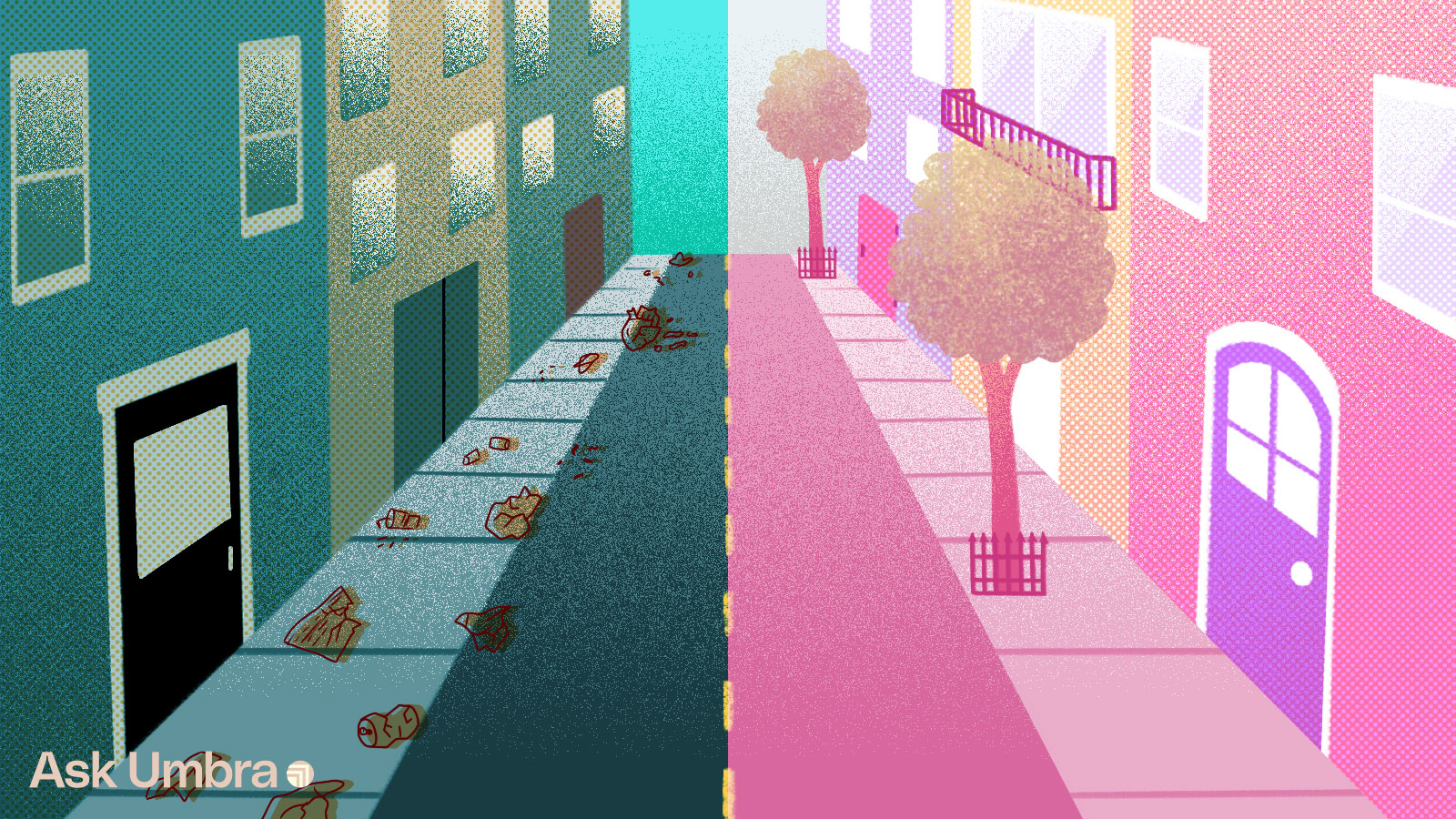

But the ways in which humans deal with trash are enormously complex! Here are two truths: Litter is generally perceived as ugly and unpleasant, and lower-income neighborhoods tend to have more litter. This isn’t, however, because people with less money care less about the cleanliness and beauty of their environment. Wesley Schultz, a social psychologist with California State University, has spent a lot of time collecting data on why people litter, and the answer doesn’t have to do much with any internal motivation or value system. A more productive question, he says, would be: When do people litter?

Turns out that litter begets more litter. If you see a sidewalk or parklet scattered with cigarette butts and beer cans and chip bags, you’re more likely to toss your own detritus there. The same is true if there’s no trash receptacle nearby.

“When we watch someone litter or see a lot of litter, we say, ‘that person doesn’t care,’ or ‘that person has values that don’t align with mine,’” says Schultz. “And that turns out overwhelmingly not to be true. Most people think that littering is wrong; most people want to live in clean environments.”

So you can see how there’s kind of a vicious cycle: Pre-existing litter inspires the idea that no one really cares how a certain area looks, so why bother keeping it clean, leading to more litter. There’s a clear corollary here in how we treat low-income neighborhoods on a society-wide scale: They are the sites of garbage incinerators, polluting industrial operations, and straight-up illegal dumping. If some company or entity is coming into your neighborhood and dumping or spewing hazardous waste everywhere, stray cigarette butts will probably seem like the least of your problems.

There’s an interesting tidbit that I found in an analysis of roadside litter in the state of Pennsylvania. More than half of all roadside litter was found to have been thrown from cars by drivers, and arterial roads and highways carry a greater concentration of litter per mile than local roads, which suggests a greater tendency to litter in a place that you’re simply passing through than in one that you call home. In the case of the Brooklyn neighborhood of Bushwick, for example, the rush of outsider revelers to new bars and restaurants created a whole bunch of new street trash — an instance of the gentrification process making a neighborhood dirtier!

Which brings us to yet another problem facing low-income neighborhoods. If you’re constantly being pushed from one neighborhood to another due to rising rents, what motivation do you have to invest in the community where you happen to have a lease? And once a neighborhood gets cleaned up and more desirable to live in, does that mean that it soon won’t be affordable for the people who already live there? When a community does get together to make a neighborhood cleaner and more beautiful and more appealing to live in, it seems wildly unfair for anyone who participated in that effort to then be pushed out.

Dave Breingan, executive director of the community development organization Lawrenceville United in Pittsburgh, suggests that community trash pickups are a really simple way to bring together newcomers and longtime residents of a neighborhood. “For people who are new to the neighborhood, I think it’s important that they understand the work that has already been done in that place by their neighbors and get to know them, and understand what the issues are for the gentrified,” he explains. “And if you’re moving into a community you do have a sense of responsibility to the people who helped make that neighborhood livable for you.”

One such community trash pickup in Pittsburgh is an annual event called the Garbage Olympics, which — full disclosure — my sister helps organize. The premise is that neighborhoods compete against one another to see who can pick up the most litter. It’s been a successful way to introduce neighbors to one another and form community bonds, and guess what? Those bonds are theoretically how you organize against policies that restrict zoning and prevent the creation of affordable housing, if displacement is a concern for you. Or, on a shorter-term scale, it’s how you get together and demand better waste infrastructure (like sidewalk trash cans and recycling receptacles) in your neighborhood!

Renée Robinson, a co-founder of the Garbage Olympics and a longtime Pittsburgh resident, acknowledges that some uncomfortable racial and socioeconomic dynamics can come into play during the pickups. “I find that more young white people are picking up trash than Black people” who already live in the community, she says, which can create friction. “Because you do want people to do things to clean your community, regardless of color or socioeconomic status, but it can be like, ‘I’m coming in to clean your community because you guys can’t take care of it.’ And I don’t have an answer to that.”

But she did advise this: If you are inspired to clean up litter in your community, see if someone is already doing just that! Oftentimes tensions arise in changing neighborhoods because longtime residents think (white) newcomers are recreating and replacing efforts that have already been underway. “Say, ‘Hey I’m new here, are there folks already doing this and how can I participate?’” she says. “‘And if there’s not, then is there a way for people who want to help start something up?’ That process can be daunting at times, but I think that’s how you don’t step on people’s toes, that’s how you build community, and it shows that you’re an ally — not, ‘I’m coming here to take over.’”

So here’s what I would caution if you, TRASH, are inspired to start your own similar enterprise in a neighborhood in which you are a newcomer. You won’t get far without the buy-in of your longtime resident neighbors, and you won’t get that buy-in with the assumption that they’re totally fine with all the trash lying around and just haven’t thought about how to deal with it. Remember: You’re trying to build a safe and clean community around your home, and that’s what all your neighbors want as well.

Collaboratively,

Umbra