This story was originally published by Mother Jones and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

Rafaela Tijerina first met la señora at a school in the town of Lost Hills, deep in the farm country of California’s Central Valley. They were both there for a school board meeting, and the superintendent had failed to show up. Tijerina, a 74-year-old former cotton picker and veteran school board member, apologized for the superintendent — he must have had another important meeting — and for the fact that her own voice was faint; she had cancer. “Oh no, you talk great,” the woman replied with a warm smile, before she began handing out copies of her book, Rubies in the Orchard: How to Uncover the Hidden Gems in Your Business. “To my friend with the sweet voice,” she wrote inside Tijerina’s copy.

It was only later that Tijerina realized the woman owned the almond groves where Tijerina’s husband worked as a pruner. Lynda Resnick and her husband, Stewart, also own a few other things: Teleflora, the nation’s largest flower delivery service; Fiji Water, the best-selling brand of premium bottled water; Pom Wonderful, the iconic pomegranate juice brand; Halos, the insanely popular brand of mandarin oranges formerly known as Cuties; and Wonderful Pistachios, with its “Get Crackin'” ad campaign. The Resnicks are the world’s biggest producers of pistachios and almonds, and they also hold vast groves of lemons, grapefruit, and navel oranges. All told, they claim to own America’s second-largest produce company, worth an estimated $4.2 billion.

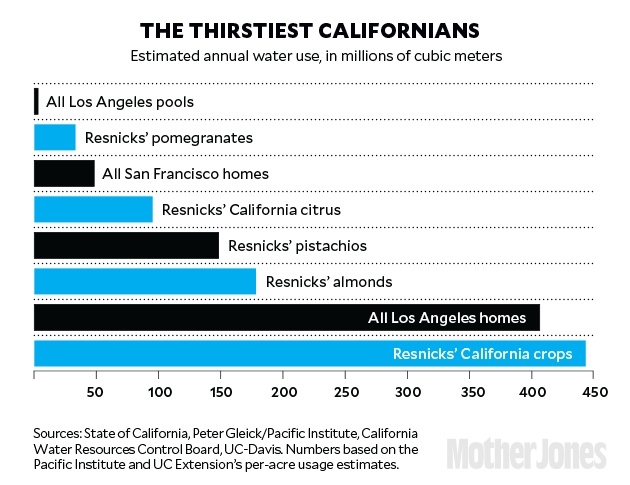

The Resnicks have amassed this empire by following a simple agricultural precept: Crops need water. Having shrewdly maneuvered the backroom politics of California’s byzantine water rules, they are now thought to consume more of the state’s water than any other family, farm, or company. They control more of it in some years than what’s used by the residents of Los Angeles and the entire San Francisco Bay Area combined.

Such an incredible stockpiling of the state’s most precious natural resource might have attracted more criticism were it not for the Resnicks’ progressive bona fides. Last year, the couple’s political and charitable donations topped $48 million. They’ve spent $15 million on the 2,500 residents of Lost Hills — roughly 600 of whom work for the couple — funding everything from sidewalks, parks, and playing fields to affordable housing, a preschool, and a health clinic.

Last year, the Resnicks rebranded all their holdings as the Wonderful Company to highlight their focus on healthy products and philanthropy. “Our company has always believed that success means doing well by doing good,” Stewart Resnick said in a press release announcing the name change. “That is why we place such importance on our extensive community outreach programs, education and health initiatives and sustainability efforts. We are deeply committed to doing our part to build a better world and inspiring others to do the same.”

But skeptics note that the Resnicks’ donations to Lost Hills began a few months after Earth Island Journal documented the yawning wealth gap between the couple and their company town, a dusty assemblage of trailer homes, dirt roads, and crumbling infrastructure. They claim the Resnicks’ influence among politicians and liberal celebrities is quietly warping California’s water policies away from the interests of the state’s residents, wildlife, and even most farmers. “I think the Wonderful Company and the Resnicks are truly the top 1 percent wrapped in a green veneer, in a veneer of social justice,” says Barbara Barrigan-Parrilla of Restore the Delta, an advocacy group that represents farmers, fishermen, and environmentalists in the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta, east of San Francisco. “If they truly cared about a sustainable California and farmworkers within their own community, then how things are structured and how they are done by the Wonderful Company would be much different.”

Lynda Resnick’s friends, on the other hand, say she has found her calling. “The work is extraordinary, and rooted in a genuine desire to make a difference in people’s lives,” says media mogul Arianna Huffington. She brushes off any notion that Resnick is in the business of charity for the sake of publicity. “She even turned me down when I asked her to write about it for HuffPost!” she told me. “She does this work because at this point in her life, it’s what she wants to do more than anything.”

In a state of land grabs and Hollywood mythmaking, the Resnicks are well cast as the perfect protagonists. But is their philanthropy just a marketing ploy, or a sincere effort to reform California’s lowest-wage industry? “If you call yourself the Wonderful Company,” Lynda Resnick told me, “you’d better damn well be wonderful, right?”

Sunset House, the Resnicks’ 25,000-square-foot Beaux Arts mansion, is imposing even by Beverly Hills standards. Its cavernous reception hall is bedecked with blown-glass chandeliers, its windows draped with Fortuny curtains, and its drawing room adorned with a life-size statue of Napoleon so heavy that the basement ceiling had to be reinforced to bear its weight. The Resnicks purchased and tore down three adjacent houses to make room for a 22-space parking lot and half an acre of lawn. The estate employs at least seven full-time attendants. “Being invited to a dinner party by Lynda Resnick is like being nominated for an Oscar, only more impressive,” local publicist Michael Levine told the Los Angeles Business Journal. Visitors have included Hollywood A-listers like David Geffen, Steve Martin, and Warren Beatty — or writers like Thomas Friedman, Jared Diamond, and Joan Didion. “I am an intellectual groupie,” Lynda told me. “They are my rock stars.”

A petite 72-year-old, Lynda has a coiffure of upswept ringlets and a coy smile. In conversation, she reminded me of my own charming and crafty Jewish grandmother, a woman adept at calling bluffs at the poker table while bluffing you back. Growing up in Philadelphia in the 1940s, Lynda performed on a TV variety show sponsored by an automat. Her father, Jack Harris, produced the cult hit The Blob and later moved the family to California. Though wealthy enough to afford two Rolls-Royces and a 90210 zip code, he refused to pay for Lynda to attend art school, so she found work in a dress shop, where she tried her hand at creating ads for the store. By the time she was 24, she’d launched her own advertising agency, Lynda Limited, given birth to three children, and gotten divorced. She was struggling to keep things afloat.

Around that time, Lynda started dating Anthony Russo, who worked at a think tank with military analyst Daniel Ellsberg. The Edward Snowden of his day, Ellsberg was later prosecuted for leaking Pentagon documents about the Vietnam War to the press. The trial revealed that he and Russo had spent two weeks in all-night sessions photocopying the Pentagon Papers in Lynda’s office on Melrose Avenue in Los Angeles. She even helped, scissoring the “Top Secret” stamps off documents to “declassify” them. “I did one naughty thing,” she told me. “But if I had to do it again, I would.”

A few years later, Lynda met Stewart Resnick. Born in Highland Park, New Jersey, the son of a Yiddish-speaking Ukrainian bartender, Stewart paid his way through UCLA by working as a janitor and went on to found White Glove Building Maintenance, which quickly grew to 1,000 employees and made him his first million before he graduated from law school in 1962. When he needed some advertising work, a friend recommended Lynda’s agency. “I never got the account,” she writes in her memoir, “but I sure got the business.” They were married in 1973.

Stewart capitalized on his wife’s marketing prowess. Their first big purchase as a couple, in 1979, was Teleflora, a flower delivery company that Lynda revitalized by pioneering the “flowers in a gift” concept — blooms wilt, but the cut-glass vase and teddy bear live on. In 1985, they acquired the Franklin Mint, which at the time mainly sold commemorative coins and medallions. Lynda expanded into jewelry, dolls, and precision model cars. She was ridiculed for spending $211,000 to buy Jacqueline Kennedy’s fake pearl necklace at auction, but she then sold more than 130,000 replicas for a gross of $26 million.

The Resnicks expanded into agriculture in 1978, mostly as a hedge against inflation. They purchased 2,500 acres of orange trees in California’s Kern County citrus belt. Ten years later, during the state’s last great drought, they snatched up tens of thousands of acres of almond, pistachio, and citrus groves for bargain prices. By 1996, their agricultural company, Paramount Farms, had become the world’s largest producer and packager of pistachios and almonds, with sales of about $1.5 billion; it now owns 130,000 acres of farmland and grosses $4.8 billion.

Along the way, Paramount acquired 100 acres of pomegranate orchards. After the Resnicks’ family physician mentioned the fruit’s key role in Mediterranean folk medicine, Lynda commissioned scientific studies and found that pomegranate juice had more antioxidant properties than red wine. By 2001 she had created Pom and soon was selling juice in little hourglass bottles under the label P♥M, a hint at its supposed cardiac benefits. Less subtle was the national marketing campaign, which showed a Pom bottle with a broken noose around its neck, under the slogan “Cheat death.”

Pom was an overnight sensation, doing millions of dollars in sales by the end of the following year — and cementing Resnick’s status as a marketing genius. “Lynda Resnick is to branding what Warren Buffett is to investing,” Gloria Steinem wrote in 2009, in one of dozens of celebrity blurbs for Rubies in the Orchard.

Sometimes, though, Resnick’s Pom claims went too far. Last year, an appeals judge sided with a Federal Trade Commission ruling saying the company’s ads had overhyped Pom’s ability to prevent heart disease, prostate cancer, and erectile dysfunction. “I think it was unfair,” Resnick told me. “And I think it’s a tragedy if the fresh fruits and vegetables that are really the medicine chest of the 21st century have to adhere to the same rules as a drug that could possibly harm you.”

It wasn’t the first time Resnick had pitched her products as health panaceas. As previously reported in Mother Jones, she marketed Fiji’s “living water” as a healthier alternative to tap water, which the company claimed could contain “4,000 contaminants.” She has pushed the cardiovascular benefits of almonds, touted mandarin oranges as a healthy snack option for kids, and called nutrient-dense pistachios “the skinny nut.” Her $15 million “Get Crackin'” campaign, the largest media buy in the history of snack nuts, included a Super Bowl ad starring Stephen Colbert. Pistachio sales more than doubled in just three months and steadily increased over the following year to reach $114 million — proving that, sometimes, money really does grow on trees.

With all this newfound wealth, the Resnicks have ratcheted up their philanthropic profile. At first, it was classic civic gifts: $15 million to found UCLA’s Stewart and Lynda Resnick Neuropsychiatric Hospital; $35 million to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art for an exhibition space designed by Renzo Piano and dubbed the Resnick Pavilion; $20 million for the Resnick Sustainability Institute at Caltech, which focuses on making “the breakthroughs that will change the balance of the world’s sustainability.” (Wonderful claims to have developed an almond tree that has 30 percent higher yields than a conventional tree, using the same amount of water.)

But in 2010 the Resnicks had an encounter at a dinner party that Lynda says fundamentally changed her approach to philanthropy. Harvard professor Michael Sandel, the ethicist known for his provocative questions, asked the assembled guests if they would be happy living in a town that was perfect in every possible way except for one terrible secret: “Everyone in the town knew that somewhere in that village, in a dank basement, there was a small 6-year-old child who was being tortured,” he said, as Resnick later recalled. “And you couldn’t say anything about the torture because if you did you had to leave the town.”

When dinner was over and they got back in the car, Lynda said, “Well, I could never allow even one child to be tortured.” Stewart turned to her and said, “But the child is being tortured, Lynda. What are you doing about it?”

“And it changed my life that very day,” she said.

When she retold the story onstage at the 2013 Aspen Ideas Festival, Resnick stopped short of spelling out exactly what she thought her husband was alluding to. Her interviewer, former CNN chair and author Walter Isaacson, didn’t press her on the matter. Nor would she elaborate when I asked her about it. By then she had certainly seen the negative stories, such as the one in the Los Angeles Times that described Lost Hills’ jarring “Third World conditions.”

Isaacson gently picked up his questioning where Resnick had left off: “And that got you involved in the Central Valley of California,” he said. “Why did you choose that?”

“Look, there’s poverty and sadness all over the planet,” Resnick replied, “but I felt that if I was really going to do work, I should start to do work in the place where our employees worked and live. That would be the most meaningful.”

“I think they ought to start looking at the farmers,” a woman in yoga pants snapped. She had just been confronted while watering her lawn in Santa Monica by one of the amateur videographers behind last summer’s hottest new California film genre: the drought-shaming video. The YouTube clip shows her being taunted repeatedly before turning to douse the camera-wielding scold with her hose.

The woman’s anger at being called out and her eagerness to redirect blame reflect common sentiments in an increasingly dry state. The Resnicks, who’ve been anticipating the drought for decades, seem shocked that it has taken everyone else so long to wake up.

“Nobody cared. No one cared about water,” Lynda Resnick told me. “These last four years with this drought, nobody was looking until it affected them. And now that people have to cut back on their water, all of a sudden it has become important.”

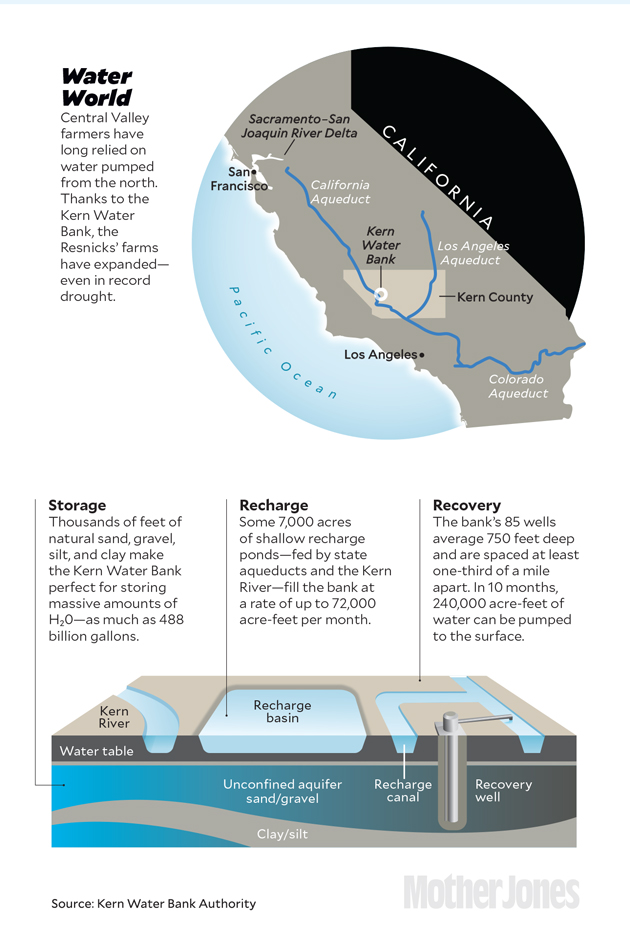

It’s true that the Golden State’s vast network of dams, reservoirs, and canals has served the state so well over the past 80 years that Californians have come to take it for granted. Assumed or forgotten is that some 8.7 trillion gallons of water will flow each day into the massive Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta, and that 20 percent of it will get sucked by huge pumps into two giant, concrete-lined canal systems and sent hundreds of miles to Southern California’s cities and farms. Delta water has transformed the arid Southland into the state’s population center and the nation’s produce aisle. But it has done so at the cost of pushing the West Coast’s largest estuary to the brink of collapse; last year the drought finally prompted regulators to eliminate most Central Valley water deliveries.

Something would have to change, and fast. The Central Valley is in some respects the ideal place to grow fruit and nut trees, with its Mediterranean combination of cool winters and hot summers perfectly promoting flowering, fruit setting, and ripening. But there’s a reason why few trees of any sort grow naturally in the Valley: It averages only 5 to 16 inches of annual rainfall, or what farmers call “God water” — just 20 percent of what’s required for a productive almond or pistachio harvest. One season without water piped in from the Delta can kill an orchard that took five years to mature. Few farmers are more at risk from the cutbacks than the Resnicks, whose 140 square miles of orchards use about 117 billion gallons of water a year, despite employing cutting-edge conservation technologies.

So like other farmers, the Resnicks have turned to the state’s dwindling reserve of groundwater, sinking wells hundreds of feet deep on their land. Farmers are the main reason that California now pumps nearly seven cubic kilometers of groundwater a year, or about as much total water as what’s used by all the homes in Texas. Sucking water from deep underground has caused the surrounding land to settle as the pockets of air between layers of soil collapse, wreaking havoc with bridges and even gravity-fed canals. Though California passed its first-ever groundwater regulations in 2014, water districts won’t be required to limit pumping for at least another four years.

Historically, farmers pumped just enough groundwater to survive, but in the middle of California’s now five-year drought, nut growers have also used it to expand. Over the last decade, California’s almond acreage has increased by 47 percent and its pistachio acreage has doubled, fueled in the latter case by the Resnicks’ advertising genius. Pistachios are now among the top 10 best-selling salty snack items in the United States, and the Resnicks’ Lost Hills pistachio factory is the world’s largest. To meet robust demand from Europe and Asia, Stewart Resnick last year announced that he wanted to expand nut acreage another 40 percent by 2020. With pistachios netting an astounding $3,519 per acre — 4 times more than tomatoes and 18 times more than cotton — he seemed confident the water would flow uphill to the money.

If you’ve watched Chinatown or read Cadillac Desert, you know something about California’s complicated and often corrupt 100-year-old fight over water rights. The state’s laws were designed to settle the frontier, and under the “first in time, first in right” rule, the most “senior” water claims are the last to be restricted in times of drought. This means some farmers are still able to flood their fields to grow cattle feed, even as residents of towns such as Okieville and East Porterville have to truck in water and shower using buckets.

But the Resnicks’ water rights, by and large, are not senior. To expand their agricultural empire, they had to find another way to tap into the flow from north to south. And to understand how they were able to do that, you have to start with a two-inch-long minnow that smells like cucumbers.

Once an abundant food source for Northern California’s dwindling salmon population, the Delta smelt has been nearly eradicated by those enormous pumps capturing the flow of water from the Sierras. In 1993, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service listed the smelt as “threatened” under the Endangered Species Act, setting the stage for pumping limits. Worried about getting short shrift on water deliveries, the Resnicks and other farmers in five local water districts threatened legal action. So in 1995, state officials agreed to a deal or, as it has been suggested, a staggering giveaway. The farmers had to relinquish 14 billion gallons of “paper water” — junior water rights that exist only de jure, since there simply isn’t enough rainfall most years to fulfill them. In exchange, they got ownership of the Kern Water Bank, a naturally occurring underground reservoir that lies beneath 32 square miles of Kern County, which sits toward the southern end of the Central Valley. The bank held up to 488 billion gallons of water, and because it sat beneath a floodplain it could be easily recharged in wet years with rainfall and surplus water piped in from the Delta. The Resnicks, who’d given up the most paper water rights, came to hold a majority vote on the bank’s board and the majority of its water.

Over the next 15 years, a series of wet winters left the bank flush with water: Court documents obtained by the Associated Press showed that in 2007 the Resnicks’ share of the bank amounted to 246 billion gallons, enough to supply all the residents of San Francisco for 16 years. The Resnicks invested in their asset, building canals to connect the bank to the state and federal water systems, thousands of acres of recharge ponds capable of sucking imported water underground, and scores of wells. According to the Wonderful vice president who chairs the Kern Water Bank Authority, the water bank “enabled us to plant permanent crops” such as fruit and nut trees.

But a legal cloud has long shadowed the Resnicks’ water deal. The Kern County Water Bank was originally acquired in 1988 by the state to serve as an emergency water supply for the Los Angeles area — at a cost to taxpayers of $148 million in today’s dollars. In 2014, a judge ruled that the Department of Water Resources had turned the water bank over to the farmers without properly analyzing environmental impacts. A new environmental review is due next month, and a coalition of environmental groups and water agencies is suing to return the water bank to public ownership. Adam Keats, senior attorney at the Center for Food Safety, describes the transfer of the water bank to the Resnicks and other farmers as “an unconstitutional rip-off.”

And here’s a key fact to consider against this backdrop: The Resnicks aren’t just pumping to irrigate their fruit and nut trees — they’re also in the business of farming water itself. Their land came with decades-old contracts with the state and federal government that allow them to purchase water piped south by state canals. The Kern Water Bank gave them the ability to store this water and sell it back to the state at a premium in times of drought. According to an investigation by the Contra Costa Times, between 2000 and 2007 the Resnicks bought water for potentially as little as $28 per acre-foot (the amount needed to cover one acre in one foot of water) and then sold it for as much as $196 per acre-foot to the state, which used it to supply other farmers whose Delta supply had been previously curtailed. The couple pocketed more than $30 million in the process. If winter storms replenish the Kern Water Bank this year, they could again find themselves with a bumper crop of H2O.

Meanwhile, the fight between farmers and smelt has plodded on, with the Resnicks becoming prominent advocates for pumping even more water south to farms. In 2007, a group called the Coalition for a Sustainable Delta began using lawsuits of its own to assign blame for the estuary’s decline to just about everything except farming: housing development in Delta floodplains, pesticide use by Delta farms, dredging, power plants, sport fishing, and pollution from mothballed ships. The coalition’s website doesn’t mention the Resnicks, but it originally listed a Paramount Farms fax number, and three of the four officers on its early tax documents were Resnick employees.

Two years later, with a federal judge now restricting Delta pumping for the sake of the smelt, the Resnicks began raising their concerns with friends in Washington. At the top of that list was California’s senior senator, Dianne Feinstein. (The Resnicks threw a cocktail party for Feinstein when the Democratic Convention came to Los Angeles in 2000; Feinstein and Arianna Huffington once spent New Year’s with the Resnicks at their home in Aspen, Colorado.) Feinstein, who chairs the Senate Appropriations Committee’s powerful energy and water panel, typically serves as the key negotiator on California-related water bills.

Responding to prodding from Stewart Resnick, Feinstein sent a letter to the secretaries of the interior and commerce urging their agencies to reexamine the science behind the Delta environmental protection plan. The agencies spent some $750,000 studying the issue anew — only to have researchers again conclude the 2007 restrictions on Delta pumping were warranted.

Lynda Resnick rejects the idea that the couple wields any political power on matters of water policy. “We have no influence politically — I swear to you,” she told me. “Nobody has political influence in this. Nor would we use it.”

Yet that’s hard to square against the Resnicks’ approach to state politics. They’ve given six-figure sums to every California governor since Republican Pete Wilson. They donated $734,000 to Gray Davis, including $91,000 to oppose his recall. Then they gave $221,000 to his replacement, Arnold Schwarzenegger, who has called them “some of my dearest, dearest friends.” The $150,000 they’ve sprinkled on Jerry Brown since 2010 might not seem like a lot by comparison, but no other individual donor has given more. The Resnicks also have chipped in another $250,000 to support Brown’s pet ballot measure to fund education.

Now, in a throwback to the sort of massive public-works projects built during his father’s governorship, Brown envisions a bold, silver-bullet solution to the state’s water crisis. He recently unveiled a $15 billion plan to construct two 40-foot-wide tunnels that could carry 67,000 gallons of water per second from the Sacramento River to the Central Valley. The tunnels would completely bypass the ecologically sensitive Delta, eliminating much of the smelt-endangering pumping — and, by extension, many of the restrictions on Delta water diversions that have crimped the Resnicks’ supply.

A win for fish and a win for farmers? Not so fast. Environmentalists fear that removing so much freshwater from the Delta will make it too salty. “You could effectively divert just about every single drop of water before it gets to the estuary in dry years,” says Doug Obegi, a staff attorney with the Natural Resources Defense Council’s water program. There are laws on the books to prevent that from happening, but Central Valley farmers are working diligently to overturn those laws. In June 2015, Rep. David Valadao, a Republican from the Valley, introduced a bill that would force federal regulators to release more Delta water for agriculture. (The Resnicks have given more than $18,000 to Valadao’s campaigns since 2011.) “They really are trying to sacrifice one region for another,” says Restore the Delta’s Barrigan-Parrilla, who will testify against the plan this fall in hearings before the State Water Resources Control Board. “If these plans come to pass, [the tunnels] are a complete existential threat to our communities, our people, and to the environment.”

But the Resnicks have never been ones to let details get in the way of a good marketing campaign. In the summer of 2014, their employees quietly began conducting polling and focus groups to figure out the best way to sell Brown’s plan. Months later they launched Californians for Water Security, a coalition of business and labor interests that promotes the tunnels as an earthquake safety measure. “An earthquake strikes a vulnerable place — the heart of California’s water distribution system,” cautions the group’s television ad. “Despite expert warnings, crumbling water infrastructure has not been fixed … Aqueducts fail. Millions lose access to drinking water … Our water doesn’t have to be at risk! Support the plan. Fix the system.”

Three weeks after the ad went live, Gov. Brown held a press conference in which he rebranded his plan as the California Water Fix.

In the heart of the nut boom is Lost Hills, an entirely flat town where more than half the households have at least one adult who works for the Wonderful Company. The population has doubled since 1990, and the influx of so many new families has meant rising costs. It’s not unusual for a field hand to spend 40 percent of his $1,800 monthly wage on a one-bedroom apartment. “You pay the rent and don’t eat, or you eat and don’t pay the rent,” says Gilberto Mesia, a Wonderful farmworker with three school-age children. More than half of the town’s residents are under the age of 23, a quarter live below the poverty line, and only 1 in 4 adults has a high school degree. “Lost Hills is extreme in every possible way,” says Juan-Vicente Palerm, an anthropologist at the University of California-Santa Barbara. “These are the state’s poorest workers, and they moved to Lost Hills because that was the cheapest place to live.”

On a swelteringly hot day, three Wonderful executives took me on a six-hour tour of nearly everything that the company is doing to improve the lives of the hundreds of employees who reside there. We met at the 14-acre, Resnick-funded Wonderful Park, where they introduced me to Claudia Nolguen, a Wonderful employee and Lost Hills native who coordinates a daily itinerary of free activities for residents. On today’s schedule: a morning fitness class, an after-school computer lab, and a movie night. We walked through the park’s emerald lawn to see its huge water tower, painted with a mural depicting two hills. “You have found Lost Hills,” the slogan said.

Next to the impeccable flower beds at one of the park’s two community centers, food bank workers were unloading enough frozen chicken to feed roughly 400 people. They were expecting a smaller-than-normal crowd. “During the harvest, families aren’t able to take advantage of the distribution,” one of the workers explained. “The usual stay-at-home mom is now working.”

We drove to the Wonderful pistachio factory for lunch. The chef in the employee cafeteria made us adobo-chicken lettuce wraps — part of a healthy menu intended to combat diabetes and obesity. Baskets on the tables were filled with free fruits and nuts for the taking. The company’s new, far-reaching health initiative also includes free exercise classes in the employee gym, a weekly on-site farmers market, and a program that pays people up to $2,700 a year to lose weight and keep it off. Since the program began in January 2015, the Wonderful workforce has shed 4,000 pounds.

In the plant’s nut-grading room, a few dozen seasonal employees wearing orange reflective vests and hairnets sat around folding tables evaluating samples from incoming truckloads of pistachios. Suddenly, a boom box started blaring merengue, and everyone stood up and danced. It was the daily Zumba break. “It feels good to move around,” one worker told me afterward.

As part of its focus on its workers, the company has built in-house health clinics at its plants in Lost Hills and Delano. The clinics have a full-time, bilingual doctor, health coaches, and prescription medications — all free of charge. “There are all sorts of costs related to poor health,” Stewart Resnick said at the Aspen Institute in July. “My hope is that this really doesn’t become a charity, but rather works, and that we will get a payback” — both in terms of productivity and reduced health care costs.

A similar return-on-investment logic infuses the company’s educational initiatives. Led by Noemi Donoso, the former chief executive of Chicago’s public school system, Wonderful Education last year spent $9.3 million, including at least $2 million on teacher grants and college scholarships in the Central Valley; it pays up to $6,000 a year toward college tuition for children of its employees. It is building a $25 million campus for a college prep academy in Delano and expanding its agriculture-focused vocational program to six public schools. It guarantees graduates of the programs jobs at Wonderful that pay between $35,000 and $50,000 a year. Among the goals is to provide a pipeline of workers to staff its increasingly mechanized operations. “Half the jobs are highly skilled jobs,” said Andy Anzaldo, the general manager of grower relations. “They’re quality supervisors. They’re engineers. They’re mechanics.”

The Resnicks are quick to point out that it’s not just plant workers who’ve benefited — the nut boom has improved the lives of farmworkers, too. Back when cotton was still king in Kern County, migrant workers who’d picked spring oranges and summer grapes in other parts of the Valley would descend on Lost Hills for a few weeks to work alongside cotton combines during the fall harvest. It wasn’t easy to bring kids along, so they usually stayed behind in Mexico or Guatemala. But tree crops are different. After the fall harvest comes winter pruning, spring pest management, and summer watering and mowing. The nut industry’s nearly year-round employment has allowed farmworkers to put down roots. They can live with their families, send their kids to school, and start to grasp for the American Dream. Like Rafaela Tijerina did.

Tijerina, who has short gray hair and a cautious smile, grew up in a village near Monterrey, Mexico, before her family moved to South Texas in 1954. She dropped out of school in the eighth grade to pick cotton and chased the cotton trail to Lost Hills, where in 1969 she found a job planting pistachio trees instead. The steady work allowed her kids to graduate from high school and move into the middle class. By 2000, Tijerina and her husband had scraped together enough money to qualify for a USDA loan that helped them buy 330 acres of wheat fields a few miles outside town.

But Tijerina and her husband can’t afford to drill wells or even tap into the supply from the local irrigation district; they farm entirely with God water. They haven’t harvested a crop in four years due to the drought, though in December they will plow their fields and plant another. Unless winter storms deliver enough rain, it will be their last shot before they sell out. “It’s really good land,” Tijerina told me, her shaky voice still tinged with optimism. “But the only thing is, we don’t have water.”