Photo: Allison SamuelsOne night in June, a young artist in cutoff jeans and paint-spattered Nike high-tops was walking down Kent Avenue in Williamsburg, a neighborhood in Brooklyn. In his hand, he carried one of the main tools of his trade: a bucket brimming with wallpaper adhesive. He planned to use the stuff to affix a giant copy of one of his linoleum-cut prints to a nearby building.

Photo: Allison SamuelsOne night in June, a young artist in cutoff jeans and paint-spattered Nike high-tops was walking down Kent Avenue in Williamsburg, a neighborhood in Brooklyn. In his hand, he carried one of the main tools of his trade: a bucket brimming with wallpaper adhesive. He planned to use the stuff to affix a giant copy of one of his linoleum-cut prints to a nearby building.

Suddenly, up drives one of New York City’s finest, lights flashing and sirens blaring. “I told him I was going to my studio,” says the artist, who works under the pseudonym Gaia. “But he knew what I was up to — I mean, why the fuck else would I be walking around with five gallons of glue? He looks at me and says, ‘You know what you’re doing is graffiti.'”

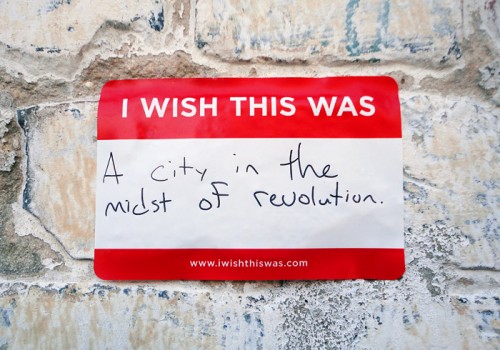

In New York, graffiti has been a code word for vandalism since the 1970s, when city hall kicked off a campaign to scrub the place clean of “style writing.” But Gaia is among a young generation of artists who are once again decorating the walls of this city and others, using street smarts and considerable artistic talent to “reactivate” urban spaces.

Street artists don’t think of themselves as graffiti writers — and they don’t fit neatly under one umbrella. They use a variety of media, including paint, yarn, block and linoleum prints, and photographs. Artists such as Shepard Fairey (best known for his ubiquitous Andre the Giant stickers and his poster of President Obama) and Banksy (the director of the documentary Exit Through the Gift Shop who once built a Stonehenge replica from portable toilets) have earned international notoriety. And now there are younger artists like Gaia, who bring environmental consciousness and an ethic of community engagement to the craft.

“They consider their work a dialog with the city,” says Martin Irvine, an associate professor at Georgetown University and owner of the Irvine Contemporary Gallery, which has shown Gaia’s work and that of numerous other street artists. “They’re saying that you can’t separate out where the art is made and where it is received … All art is site-specific … It’s as revolutionary as Pop Art’s redefining of what an art object can be.”

Photo: Gaia

Photo: Gaia

Gaia, a 23-year-old who spent his formative years on the Upper East Side and is now based in a factory-turned-semi-legal-artist-hive in Baltimore, says much of his early work was inspired by a sense of looming environmental calamity. “I wanted to express this strange un-locatable feeling of fear about the end of the world — my generation’s zeitgeist of global warming,” he says.

Four years ago, his haunting, intricately carved linocut prints of animals and animal-human hybrids began to appear on the sides of derelict buildings, in alleys, and abandoned billboards around Baltimore. They were signed only “Gaia,” a name he took from the Greek earth goddess, though it was also appropriated in the ’70s by a couple of mad hippie scientists to describe their theory that the earth is a single living organism.

Eventually, Gaia’s encounters with the people who lived in these places, and his curiosity about urban history and planning, set him on another course. His recent work, he says, engages specific questions about the places he works: “Why is this neighborhood rotting? Who built these projects? Why are they being demolished? What was the history of this site?”

Earlier this year, he did a series of portraits of well-known urban planners, architects, and developers, including Robert Moses, Minoru Yamasaki, and James Rouse, pasting them up in areas where these men worked — though they may be largely forgotten by the people who pass their days there. To help raise money for Baltimore’s ragtag Edgar Allan Poe museum, he created a print of a raven, donating copies to the museum for sale and affixing a giant double print to the side of the nearby Poe Homes low-income housing projects.

Photo: Gaia

Photo: Gaia

“He got to know the people in the neighborhood, and the ravens became a place where people went to get their pictures taken,” says Doreen Bolger, director of the Baltimore Museum of Art, who has followed Gaia’s work. “Unlike graffiti artists and paint bombers, who use their work to mark territory, in meaning and in method, he becomes part of the community.”

Of course, Gaia has had his share of run-ins with law enforcement over the years. He has, on occasion, had to take down an installation — or abandon one he’d planned to put up, as was the case that summer night in Williamsburg. But he has talked his way out of many a tight spot, and he has never been arrested for putting up his work.

And oddly enough, Gaia’s nocturnal mischief has propelled him into the inner sanctum of the art world. Galleries from Washington, D.C., to Chicago, San Francisco, and L.A. have exhibited his work. In September, he spent several weeks in Miami, contributing a mural to Wynwood Walls, a project underwritten by developer Tony Goldman.

“Miami was cushy. The cushiest thing that has ever happened,” Gaia says, describing his hotel room on Ocean Drive and “$400 per diem just to spend on Cuban food and cigarettes.”

Photo: Gaia

Photo: Gaia

His Wynwood Walls mural is a portrait of oil tycoon-turned railroad magnate Henry Flagler. To house Miami’s largely African American workforce, Flagler created a neighborhood called Overtown in the shadow of his burgeoning shipping enterprise. The neighborhood saw something of a renaissance following World War II (Muhammad Ali once trained there) but was drawn and quartered during the age of “urban renewal” by an expressway and an interstate.

By accepting the sweet assignment at Wynwood Walls, isn’t Gaia contributing to the very kind of urban redevelopment and gentrification he has criticized in the past?

“Gentrification is seen as a dirty word,” he says. “But we’re getting better at gentrifying neighborhoods. The least sensitive was urban renewal, where they cleared entire swaths, displacing entire populations of people. We tried corporate downtowns, stadiums, high rises, all different incentives … We’re coming to a more nuanced vision of revitalizing a neighborhood, and that is something that Tony Goldman embodies.”

Once again, he manages to talk himself out of a tight spot. Can it last? Time will tell. For now, he’s off to Europe, where he’ll take part in the lively legal mural scene that is spreading across that continent in the bright light of day.

In the meantime, his work stateside, protected from the elements only by a crust of dried wallpaper paste, fades. “His materials deteriorate and crumble. His work is as fragile as the city,” says Bolger. “It just disappears.”

This is the first of a series of stories about street art. Next, meet a doctor-turned muralist who has taken the art form to the Navajo Nation.