Jewelry stand in Bitter Springs.Photo: JetsonoramaThe original inhabitants of the land that is now the Navajo Nation knew something about writing on walls. Spend any amount of time kicking around this canyon country and you’ll find symbols and images painted and etched into the stone. Though street art might seem like a similar art form, born from similar impulses generations later in cities such as New York and LA, finding it here in its modern form seems unlikely: You can drive for hours and see little sign of human life, save for an occasional passing pickup truck or a hogan tucked into the scrub.

Jewelry stand in Bitter Springs.Photo: JetsonoramaThe original inhabitants of the land that is now the Navajo Nation knew something about writing on walls. Spend any amount of time kicking around this canyon country and you’ll find symbols and images painted and etched into the stone. Though street art might seem like a similar art form, born from similar impulses generations later in cities such as New York and LA, finding it here in its modern form seems unlikely: You can drive for hours and see little sign of human life, save for an occasional passing pickup truck or a hogan tucked into the scrub.

But it’s here. There’s old-style graffiti, sure, and, as anywhere, a lot of puerile scrawling. But in the past few years, a new hand has been at work, posting giant photographs of the faces of Navajo people on water tanks, abandoned gas stations, roadside jewelry stands — even the announcer’s booth at the rodeo grounds in Tuba City.

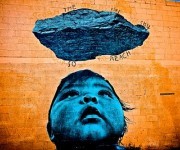

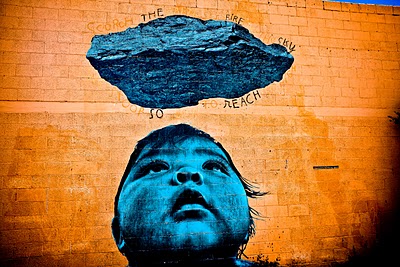

Of late, these images have taken on an activist bent, serving as stark harbingers of climate change or bold statements against a ski area’s development plans in a sacred mountain range. One of the most recent installations — a collaboration with the climate action group 350.org that appeared around the reservation and in the town of Flagstaff — depicts a giant chunk of coal hovering over the wide-eyed face of a Navajo infant.

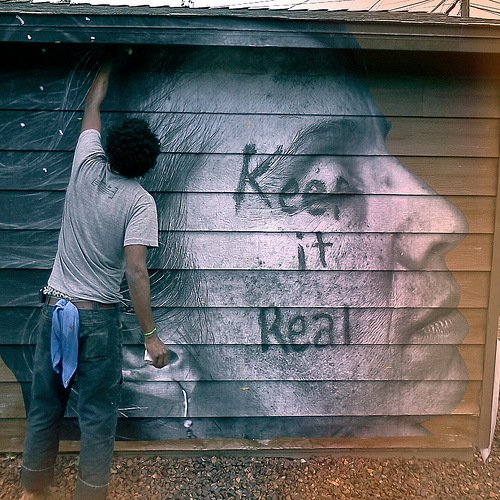

Jetsonorama installs an image of photographer and artist Raechel Running.Photo: Xomiele

Jetsonorama installs an image of photographer and artist Raechel Running.Photo: Xomiele

The man behind these images is no spring chicken. He’s a 54-year-old physician who has worked with the Indian Health Service on the reservation since 1987. His identity is no secret on the rez — many of his images are of friends and acquaintances. Still, his work is not entirely above board. He prefers to be known only by his pen name, Jetsonorama. (Jetson was the name of his first dog, if you must know. The “orama” part is kind of a long story.)

Jetsonorama was in med school during the heyday of hip-hop and made regular forays into New York City to see break dancers and style writing spray-painted on train cars. He moved to the Navajo reservation in 1987 to work off a government-funded education and fell in love with the place. A trip to Brazil in 2009 turned him on to the rush of nighttime street-art bombing runs. He’s been putting up his own images since 2009.

“It’s the last place that people would expect to see street art,” he says of the reservation. “But the art is the result of me having spent 23 years living with Navajo people. I don’t know that many of my images would work as well in an urban setting.”

Besides, he says, “My primary audience on the reservation is a vehicle traveling at 70 miles per hour. In order to get attention of said vehicle, my image has to be pretty big.”

His favorite target of late is roadside outhouses.

Raising awareness of climate change with 350.orgPhoto: JetsonoramaThe infant-and-coal image came about because of a challenge form 350.org, which asked street artists around the world to create work that spoke to the local connections to climate change. The Navajo Nation is home to the Kayenta coal mine on Black Mesa, which churns out fuel for a nearby power plant.

Raising awareness of climate change with 350.orgPhoto: JetsonoramaThe infant-and-coal image came about because of a challenge form 350.org, which asked street artists around the world to create work that spoke to the local connections to climate change. The Navajo Nation is home to the Kayenta coal mine on Black Mesa, which churns out fuel for a nearby power plant.

“If the Navajo people and coal were to declare their relationship status on Facebook, they’d have to choose the ‘it’s complicated’ option,” Jetsonorama wrote in his blog after interviewing more than a dozen coworkers about their views about coal.

The mine and power plant offer some of the few middle class jobs on the reservation, he says, and many tribal members think of coal as a cheap way to heat their homes ($60 for a pickup truck load, vs. $200 for load of firewood).

At the same time, the Navajo recognize the health problems that come from breathing coal smoke. And the irony is not lost on these people that the electricity generated with Black Mesa coal doesn’t stay here — it keeps the lights on in Phoenix, Las Vegas, and LA.

Words about the San Francisco Peaks on Navajo faces.Photo: JetsonoramaAfter the 350.org project, Jetsonorama teamed up with activists fighting a ski area’s plans to use treated wastewater for snowmaking on the San Francisco Peaks above Flagstaff, Ariz. The activists painted their faces with messages about the mountains. Jetsonorama photographed them, then installed giant enlargements of the images on walls.

Words about the San Francisco Peaks on Navajo faces.Photo: JetsonoramaAfter the 350.org project, Jetsonorama teamed up with activists fighting a ski area’s plans to use treated wastewater for snowmaking on the San Francisco Peaks above Flagstaff, Ariz. The activists painted their faces with messages about the mountains. Jetsonorama photographed them, then installed giant enlargements of the images on walls.

“We’ve marched. We’ve tied ourselves to machinery. We’ve voiced our opposition at city hall meetings. A lot of times, it’s fallen on deaf ears,” says Navajo artist and activist Shonto Begay, one of the people pictured in the recent murals. “This is another form of communicating that message. I think it’s working. It just grabs you.”

As non-native working on native soil, Jetsonorama is bound to raise questions of authenticity, but Begay says that the artist has been excepted into the community. “If it were somebody that just came in and appropriated our knowledge and our stories — like Tony Hillerman — that would be different. It would be frowned upon,” Begay says. “But he’s been on the reservation for 20 or 30 years. This is home.”

Jetsonorama’s work is all in black and white, Begay adds, which gives it “a sense of oldness that we only see in photos of our old grandparents. You get that sense of awe, that sense of history.”

Jetsonorama says that working on the reservation and dividing his time between working as a doctor and a street artist do bring unique challenges. “As physician, it forces me to be accountable for that work,” he says. “And the Navajo people have large extended families. My responsibility is to the entire family.”

But he hopes his art complements his day job. “I try to put a positive vibration out there,” he says. “If it brings a moment of happiness or restores health, then for the small amount of time that image is out there, it serves its purpose.”

(h/t Erik Hoffner)

This is part of a series of stories about environment-related street art. Next, meet a woman who spent weeks kicking around New York with a sports-field chalker in an effort to raise awareness of climate change.