What would you do if you had a million bucks to make your neighborhood better? Turn the vacant building up the street into a healthy corner store with cross-cultural appeal? Fund 24-hour bus service? Paint giant flowers on the asphalt in every intersection?

What if there was a tool that made it easy for you share your idea with neighbors, community groups, city planners — people who could pitch in to make it a reality?

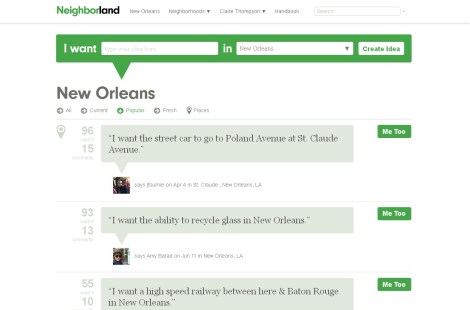

That’s the idea behind Neighborland, a sort of collective online urban planning platform that grew from a project started by artist Candy Chang in 2010. Chang slapped nametag-style stickers reading “I WISH THIS WAS ___” on abandoned buildings around New Orleans. People answered by filling in the blanks with all sorts of things they’d like to see in their neighborhoods: a grocery store, a row of trees, a bakery — to which someone else responded, “If you can get the financing, I will do the baking!”

“People were trying to talk to each other,” says Alan Williams, Neighborland’s director of community, who met with me on a rainy day in New Orleans two weeks ago to show me some of the group’s work. “What if [the conversation] wasn’t lost to time? What if people could share knowledge and expertise?”

Neighborland allows the kind of organic conversations started by the stickers to happen online, where they can build momentum and facilitate connections. Neighborland users (there are a core group of them who engage regularly, Williams said) post what they want for the city overall or for a specific neighborhood, and others can click “me too” or comment. Ideas can be sorted by most recent or most popular. Suggestions range from the general (“I want more food trucks in New Orleans”) to the specific (“I want an African-American bookstore at the Historic LaSalle Corridor”), from the heavy (“I want zero tolerance gun laws in New Orleans”) to the whimsical (“I want a recycled glass monument to our lack of glass recycling”).

Other online idea-sharing tools like this already exist, of course, and Neighborland has aspects in common with each of them. There’s Mindmixer, a “virtual town hall”; Change by Us, where citizens can propose projects and connect with others who want to work on them; and Ioby, sort of a sustainability-focused Kickstarter.

“What’s different about Neighborland is we’re trying to build support for existing ecosystems,” Williams says. “We didn’t want to create a separate community, we wanted to provide a tool for the existing community. For almost every idea someone has about their neighborhood, somebody’s already working to make that change happen.” Neighborland serves as a forum to collect those ideas and, with Williams’ help, direct them to the people with the power to make them reality.

For example, one popular idea among Neighborland users was making the GPS data maintained by the New Orleans Regional Transit Authority (RTA) open to the public, to make it possible to create apps showing when the next bus or train will arrive, like the Bay Area’s NextBus or Seattle’s OneBusAway. So Neighborland contacted a community group called Transport for NOLA, which already had the tools and organization to help successfully advocate with RTA. Transport for NOLA is also supporting RTA’s efforts to apply for federal funding to extend a new streetcar line — the most popular idea on the Neighborland site, Williams says. And the enthusiasm for this improvement, shown on Neighborland, got the attention and support of the city councilmember who represents the affected neighborhoods, so she can now add her leverage to the campaign.

“Public officials have a lot of competing demands for their attention,” Williams said. “Not only does Neighborland show what people want, it shows their priorities. It’s providing value to all community leaders.”

It’s the job of elected officials to listen to their constituents. But Neighborland makes it easier for citizens to add their voices to an ongoing conversation. It’s as simple as seeing someone else’s idea and clicking a button that says “me too” — similar to a Facebook “like.” The platform provides a concrete, but continuously evolving, record of the needs and desires residents have for their neighborhoods.

“You shouldn’t have to be able to go to public meetings and do time-intensive things to have a voice,” Williams says.

Nor should you have to be online. Neighborland stays true to its street-art roots by recognizing that public spaces are important venues for communication, especially for citizens who aren’t as web-savvy. Its staff, sponsors, and community partners helped spread the word about the site through physical installations at New Orleans’ many festivals and street fairs, distributing stickers with the web address on the bottom. “We’re still working to get people who don’t use the internet regularly for community activism to see it as an everyday tool,” Williams said.

Neighborland still maintains a physical presence around town. A sign in the window of a building called the Saratoga in New Orleans’ Central Business District asks people waiting at the bus stop outside to text their ideas for the spot to a certain number. Williams asks if I have any ideas and I come up with cooling fans for the bus stop — the southern alternative, I figure, to heat lamps, always a godsend at Chicago’s L stops in the winter. I text the number and, a minute later, there’s my idea on the site, among dozens of others people outside the Saratoga have texted over the months: a falafel joint, a hair salon, “a small venue for teens & young adults,” and “a 24-hour bodega that sells cat food, scotch tape, flowers, coffee, and egg & cheese sandwiches.”

It makes sense that an idea like Neighborland would have been born in New Orleans, a city whose palpable creative energy and funky charm can distract visitors from structural breakdowns like a lack of municipal recycling, still frequently flooded streets, and a murder rate at least 10 times the national average. In New Orleans, “Hurricane Katrina discredited the status quo,” as Williams put it, meaning “people understood we couldn’t go back to the way things were. People in New Orleans are more willing to try new things.”

Now Neighborland is expanding to other cities: The site is live in Boulder, Colo., and testing in Houston, with plans for a national rollout. Even without dedicated staff yet beyond New Orleans, the model seems to be working in other locations. In Houston, Williams said, someone said they wanted a particular intersection to be safer for bikes. A traffic engineer who saw the idea was able to change the timing of the stoplight there.

Williams acknowledges that the changes Neighborland has spawned so far don’t constitute a dramatic overhaul of the city’s infrastructure. But in some ways, that’s the point — collaborative, community-level urban planning may be incremental, but this “tactical urbanism” responds directly to what people are asking for. “We think there’s a lot of value to being tactical,” Williams said. “We’re doing something that may be temporary, maybe it’s just a small gesture, but you’re showing things can be different. We’re focused on making these small but important changes add up.”