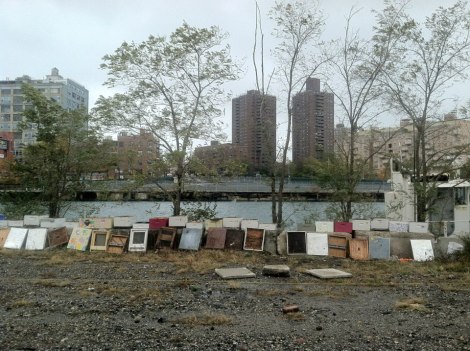

Yesterday, we brought you the sad story of the Brooklyn Grange’s lost beehives. Today, there’s more bad news on the urban farm front in New York City. From Brooklyn to Manhattan, some farms fared OK while others were entirely drowned.

Brooklyn GrangeSome of the Grange’s destroyed beehives.

The New York Observer reports:

The Red Hook Community Farm was under more than two feet of water during the storm, executive director Ian Marvy told us. Even the crops that remain after flooding are a total loss and cannot be sold or donated because of water pollution. The farm also lost two bee hives; it’s unclear how much of the equipment can be salvaged.

It is likely that flood waters also destroyed Battery Urban Farm in Lower Manhattan. Phones were not working and emails to staffers went unanswered, but reports of extensive flooding on the streets surrounding the farm leave little doubt that the agricultural operation is more than likely done for the season, if not longer.

It was a pattern that played out consistently across the city: the bees, birds and the plants withstood the gale’s winds, but not even the most diligent preparations could stop the floods.

While some of New York’s local food-security dreams were drowned this week, farmers at East New York Farm, Gotham Greens, and elsewhere were spared the worst and remain hopeful about rebuilding in the future.

But that’s a future that’s full of potential for more Hurricane Sandys. At Mother Jones, Tom Philpott reflects on extreme weather’s impact on farming beyond urban areas, from this summer’s massive drought to superstorm Sandy. It’s too early to assess Sandy’s damage to farms in the affected region, he says. But what about next time?

[T]here’s nothing you can buy in a bag that can protect a crop from flood or withering drought. During the great floods of June 2008, Midwestern farm fields were losing nitrogen fertilizer at the rate of 4 percent per day. And during this summer’s drought, neither all the fertilizer in the world, nor GMO crops, could save the Midwest’s vast corn fields from severe losses.

As the great Iowa State University agricultural thinker Fred Kirschenmann observed earlier this year, we have for decades been designing agriculture for “maximum, efficient production for short-term economic return,” based on the assumption of relatively stable weather and cheap fossil resources. But now weather has turned chaotic and energy prices have become volatile. Kirschenmann made the obvious point that we need to develop a farming system that’s “more resilient and productive in unstable conditions.”

What’s less obvious: It’ll be a challenge to develop those systems in cities like barely-above-sea-level New York, which, while dense and green and innovative, are most vulnerable to the effects of our new extreme weather. Then again, some of those high-up rooftops still look inviting for a garden or two.