Lori Rotenberk

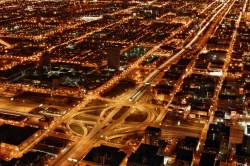

Cermak Road on Chicago’s West Side is a historic, industrial artery that time almost forgot. The area is cluttered with smokestacks and corrugated steel warehouses, crisscrossed with train tracks and barbed wire fencing, viaducts and underpasses. At its center stands the brick edifice of the soon-to-be-shuttered Fisk coal-fired power plant.

It comes as something of a surprise, then, to learn that this week, city officials will unveil a dramatic overhaul that they say makes a 1.5-mile stretch of Cermak Road the greenest street in the country, and possibly the world.

The unlikely marriage of sustainability and this gritty corridor isn’t accidental. The Chicago Department of Transportation has spent two years and $16 million on this stretch of Cermak, which serves as the southern gateway to the city’s Pilsen neighborhood. David Leopold, project manager for the CDOT, says he took everything that would make a building LEED platinum and built it into the streetscape. Improvements range from solar-paneled bus stops to native plants and pavement that sucks up rainwater. Other cities are studying the project as a blueprint for change.

Lord knows a little change was in order for Cermak Road. Pedestrians stepping off buses on the street’s south side had to navigate mud puddles and a nearby rail spur. On the north side, workers, tired of losing mirrors and doors to passing trucks, parked on the sidewalks.

Lori Rotenberk

CDOT engineers at first planned to give Cermak the usual not-so-eco-groovy upgrade. Leopold, however, saw the raw beauty — and how good it would look in green. Armed with TIF (Tax Increment Financing) funds and grant money, CDOT set to work, incorporating what Leopold believes is the greatest number of sustainable elements ever to go into a single stretch of road.

The Cermak/Blue Island Sustainable Street Scape, as it is now known, has already elicited wonder. On a recent tour of the area, Danny Solis, alderman of the 25th ward comprising Pilsen, said he’s taken calls from residents wondering if the spinning wind turbines powering educational kiosks “are communication devices for outer space.”

Leopold, yelling over the din of traffic, said he was hoping for a sudden thunderstorm so he could show off all the new stormwater features. Spotting the twiggy mesh of a bird’s nest in a newly planted tree, he exclaimed, “Look! We’ve created habitat!”

As he walked, Leopold explained the rules that CDOT set for the project. Materials had to be found within a 500-mile radius of Cermak, he said. All told, 23 percent of the materials used in the project were recycled, and more than 60 percent of the project’s construction waste was recycled in turn.

Lori Rotenberk

And recycling is just the start of it. Sidewalks and asphalt have been designed to reflect summer’s light and heat. Inside traffic lanes are coated with self-cleaning photocatalytic cement, absorbing nitrogen oxide from car traffic, thus cleaning the surrounding air. Overhead, new energy-efficient streetlights bow toward the street, drawing power from solar panels and cutting back on nighttime light pollution.

The street is now lined with 95 different species of native plants, grasses, shrubs, and trees. Some will grow to mask train tracks and fences. Everything growing is irrigated by storm runoff via bioswales, permeable pavement, and infiltration planters, all diverting 80 percent of the annual rainfall from overloaded city sewers. For the students of Benito Juarez Community Academy, CDOT coupled with an already planned school expansion, adding a gathering area around a creek that fills with rainwater from spouts and bioswales.

The addition of new sidewalks and parking spaces creates a place for cars to park at a curb, rather than where people want to walk. Installation of a “pedestrian refuge island” in the middle of Cermak Road puts an end to the hazardous standing amid east/west traffic, attempting to cross. Coming soon: long-awaited permeable-paved bike lanes that will finally tie Cermak to a web of routes leading into the city.

ShutterstockOne and a half miles down. Just 5 million to go …

The changes have not altered Cermak’s overall industrial feel — in fact, aside from all the plants, the place doesn’t look dramatically different from any other well-designed streetscape. It’s mainly what’s inside and underneath that has changed.

Tim Samuelson, the City of Chicago’s cultural historian, says there’s a similar transformation underway in the old warehouses and factories along Cermak Road. The area boomed during the turn of the century due to its proximity to the Chicago River, railroads, and the city’s Loop, he says — and while the old industries are largely gone, they’re being replaced by businesses that specialize in recycling and reuse.

Samuelson, who brings visitors to Cermak to get a taste of old, industrial Chicago and a meal at the local greasy spoon, Steak n’ Egger, finds the contrast between past and present interesting. “It’s an area where industry is redeveloping itself for a new age,” Samuelson says. “And it’s interesting how both the industry and the street is meeting the change head on.”