Name one landscape architect. Any one will do. No, I’m not talking about the guy who does your landscaping — I’m looking for genuine, bona fide landscape architects, the ones who analyze, plan, design, manage, and nurture natural and built environments.

What was that? “Frederick Law Olmsted?” You mean the grandfather of landscape architecture, the man who built Central Park? Good. Now name a landscape architect who hasn’t been dead for more than a hundred years.

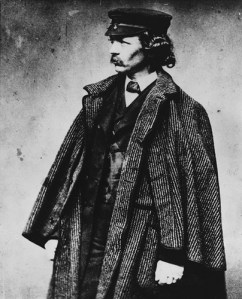

Hello? Can you tell me who designed the High Line, the most famous urban park in the country right now? You can’t. That’s what I thought. Well, for future reference, it’s this guy, James Corner — but that, right there, is my point:

The present generation of landscape architects is doing truly groundbreaking work, building parks like the High Line in places nobody expects them. If Olmsted is a classical composer of yore, James Corner and his contemporaries are like Lady Gaga. They’re like Bob Dylan plugging in. They’re the electric guitar after years and years of classical music. BUT YOU’VE NEVER HEARD OF THESE PEOPLE!

And so, on Olmsted’s 190th birthday (April 26 — prepare your celebratory picnic baskets!), I decided it’s time to show these landscape architects a little love.

But first, allow me to geek out about Olmsted for a quick sec. I can’t help it. I wrote and produced a documentary film about the guy. Plus, to understand the revolutionaries working today, you have to understand where they came from.

Central Park, New York City. (Photo by asterix611.)

People still, after all these years, love Olmsted’s parks. Just check out Central Park on a sunny day. Or Prospect Park in Brooklyn. Or the Emerald Necklace that winds through the neighborhoods of Boston. Or the park systems in Louisville and Buffalo. The man carried out over 500 commissions to design urban parks, parkways, park systems, residential communities, college campuses, government buildings, and country estates. His sons, Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. and John Charles Olmsted (who was technically Olmsted’s nephew — it’s a long story) designed thousands more, including major city plans for Baltimore and Seattle.

Olmsted landscapes are practically trademarked — rolling hills, open meadows, patches of thick woodlands, wide, winding paths. Olmsted didn’t want you to notice the design — and, unless you’re looking for it, you don’t. The man even hated flowers because they call too much attention to themselves. You’re supposed to lose yourself in Olmsted’s parks — the paths were designed so that you’d never come upon a right angle and have to ask yourself, “Which way?”

The High Line, New York City. (Photo by David Berkowitz.)

Turns out that tired, overworked city dwellers really appreciated this — which is why it’s still hard to find a blanket spot in Sheep Meadow on a Sunday in June. But for all the reverence Olmsted still earns from the public, he set the bar so high that many landscape architects resent him. In an interview filmed for the documentary, urban studies expert Witold Rybczynski told us:

It’s a little bit like being a composer right after Mozart or Beethoven. People just want more Mozart or Beethoven. They’re not interested in Joe Smith — you know, they’ve been exposed to something, and they just want more of it … I mean he’s bigger than Mozart, because he doesn’t just do great parks, he also sort of invents the whole profession. It’s as if Mozart invented musical composing, which of course he didn’t.

In a literal sense, landscape architects today can’t live up to Olmsted’s legacy. There just isn’t enough space. When Olmsted and Calvert Vaux built 843-acre Central Park, which starts on 59th Street, they built it on farmland. At the time, Manhattan’s development stopped at 23rd Street. Today, we’re building parks on abandoned, elevated railroad tracks and old brownfield sites, and we have to do more with less — the majority of urban parks built in the last decade are fewer than 15 acres.

But today’s urban parks are changing the way people interact with cities, just as Olmsted’s were.

Citygarden, St. Louis. (Photo by dishfunctional.)

Nobody looks at Citygarden in St. Louis — equal parts sculpture garden, botanic garden, and city park — and comments on how natural it is. Designed by Nelson Byrd Woltz Landscape Architects, based in Charlottesville, Va., Citygarden pays homage to the cultural and natural histories of the city in its own way. The 550-foot long arching wall made of locally quarried rock may have been too conspicuous for Olmsted, but it echoes the bends and bluffs of both the Mississippi River and the city’s famed Gateway Arch.

Civic Space Park in Phoenix, designed by a team at the Fortune-500 design firm AECOM, has a splash pad and a field of LED-lit columns which come alive nightly in a light show meant to mimic the lightening of an Arizona summer. The park also has a crazy wormhole sculpture suspended in air called Her Secret is Patience. It was designed and built by Janet Echelman of painted, galvanized steel and cables, polyester twine netting, and changing, computer-controlled colored lights. It is meant to make the patterns of the desert winds visible to the human eye.

Civic Space Park, Phoenix. (Photo by RightBrainPhotography.)

The new design for Chicago’s Navy Pier — another project of James Corner Field Operations — has an indoor “crystal garden” with hanging “vegetable pods” straight out of Avatar. The pier, originally designed by Daniel Burnham in 1909, was meant to connect the citizens of Chicago with Lake Michigan. Corner’s floating pool at the end of the pier will do this quite literally.

And suddenly, urban parks are cool again, and not in the way they’ve always been (It’s springtime, let’s have lunch in the park!) but in a way that makes the act of actually designing them look really impressive and hip.

But the more this new guard of landscape architects tries to distance themselves from Olmsted, the more, in the end, they resemble him.

The thing is, Olmsted was creating landscapes in the 19th century, but his work is as relevant today as it ever was. That’s what made him so visionary: He was an innovator who looked ahead. Here’s the future he saw for New York in 1859:

The time will come when New York will be built up, when all the grading and filling will be done, and when the picturesquely-varied, rocky formations of the Island will have been converted into foundations for rows of monotonous straight streets, and piles of erect, angular buildings. There will be no suggestion left of its present varied surface, with the single exception of the Park.

Eschleman’s sculpture in Civic Space Park may not be floating in all its Technicolor glory in the year 2170. But the resourcefulness that today’s crop of landscape architects has inspired will be indispensable in the future, as the amount of open space in cities continues to decline. Then, all the landscape architects will be complaining about James Corner.