A big reason for opposition to bike lanes is that, according to the rules of traffic engineering, they lead to car congestion. The metric determining this outcome (known as “level of service”) is quite complicated, but its underlying logic is simple: less road space for automobiles means more delay at intersections. Progressive cities have pushed back against this conventional belief — California, in particular, has led the charge against level of service — but it remains an obstacle to bike lanes (and multi-modal streets more broadly) across the country.

But the general wisdom doesn’t tell the whole story here. On the contrary, smart street design can eliminate many of the traffic problems anticipated by alternative mode elements like bike lanes. A new report on protected bike lanes released by the New York City Department of Transportation offers a great example of how rider safety can be increased even while car speed is maintained.

To see what we mean, let’s take a look at the bike lanes installed on Columbus Avenue from 96th to 77th streets in 2010-2011. As the diagram below shows, the avenue originally had five lanes — three for traffic, one for parking, and one parking-morning rush hybrid. By narrowing the lane widths, the city was able to maintain all five lanes while still squeezing in a protected bike lane and a buffer area.

NYC DOT

Rather than increase delay for cars, the protected bike lanes on Columbus actually improved travel times in the corridor. According to city figures, the average car took about four-and-a-half minutes to go from 96th to 77th before the bike lanes were installed, and three minutes afterward — a 35 percent decrease in travel time. This was true even as total vehicle volume on the road remained pretty consistent. In simpler terms, everybody wins.

Over on Eighth Avenue, where bike lanes were installed in 2008 and 2009, the street configuration was slightly different but the traffic outcome was the same. Originally, the avenue carried four travel lanes, one parking lane, one parking-rush hybrid, and an unprotected bike lane. Again, by narrowing the lanes, all five were preserved (though the hybrid became a parking lane) even as riders gained additional protection.

NYC DOT

After the changes, traffic continued to flow. DOT figures show a 14 percent overall decline in daytime travel times in the corridor from 23rd to 34th streets once the protected bike lanes were installed. That quicker ride was consistent throughout the day: Travel time decreased during morning peak (13 percent), midday (21 percent), and evening peak (13 percent) alike. To repeat: A street that became safer for bikes remained just as swift for cars.

So what happened here to overcome the traditional idea that bike lanes lead to car delay? No doubt many factors were involved, but a DOT spokesperson tells CityLab that the steady traffic flow was largely the result of adding left-turn pockets. In the old street configurations, cars turned left from a general traffic lane; in the new one, they merged into a left-turn slot beside the protected bike lane (below, an example from 8th and 23rd). This design has two key advantages: First, traffic doesn’t have to slow down until the left turn is complete, and second, drivers have an easier time seeing bike riders coming up beside them.

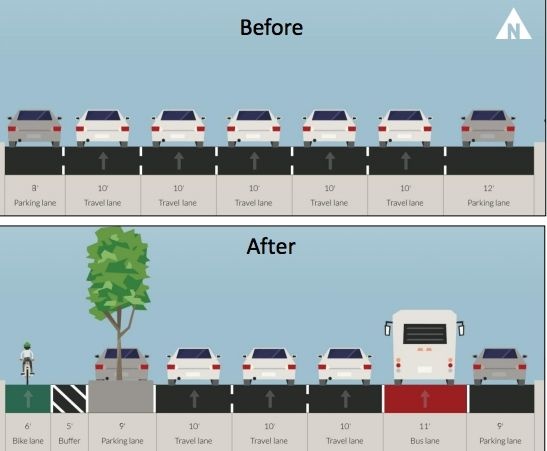

For good measure, let’s also look at mobility on First Avenue, where protected bike lanes were added up to 34th Street in 2010. The design of First Avenue was dramatically altered. What was previously five travel lanes and two parking lanes for cars became three travel lanes, two parking lanes, a bus lane, and a protected bike lane — a significantly more balanced travel network.

NYC DOT

Despite all the changes, travel speeds remained just about the same as they had been before. Average daytime taxi speeds dropped maybe one mile per hour after the reconfiguration, according to DOT figures. But that minuscule delay was likely countered by an overall rise in mobility: Bicycle volume increased 160 percent, for instance, in addition to whatever transit gains the bus enhancement provided.

So we see an example, in the busiest city in America, of smart street design improving travel for everyone. That’s not to suggest you can jam unlimited new modes onto a given street and still have everything move well. But it does show that just because a city values travel alternatives over car-centric engineering doesn’t mean that city’s traffic has to come to a halt.

This story was produced by The Atlantic’s CityLab as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

This story was produced by The Atlantic’s CityLab as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.