When I lived in Boston, I was impressed, as so many other residents have been before me, by how the city’s street grid made no sense. For example: It isn’t even, technically, a grid at all.

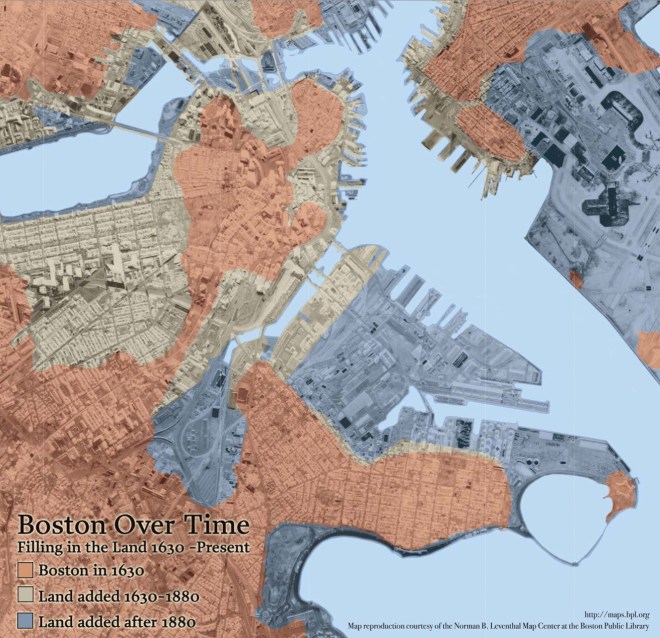

There are a variety of reasons for this: Boston is an old city. It was already fairly built-out before anything approaching urban planning came into the picture. But there’s another reason: Boston used to have a lot more waterfront than it does today.

In the days before combustion engines, water was the easiest way to move stuff around. And so the streets of Boston, while confusing as hell now, originally served the very sensible purpose of helping the city’s residents get to the water as quickly as possible. It’s not the streets’ fault that people kept on making more land and pushing the water out. Over half of Boston is former marshes and tidelands.

Now Boston’s old waterfront is coming back, and how. According to climate models, Boston Harbor’s sea level is predicted to rise as much as five or six feet by 2100. As climate change begins to do its thing, Back Bay, the South End, and Logan Airport will go back to becoming underwater real estate for at least part of the year. Parts of the waterfront have already begun to flood monthly, during the city’s “wicked” tides, which get very, very high.

Boston is dealing with this development in a way that is very of the moment: It’s holding a contest based on the concept of “living with water” — a way of managing periodic flooding popularized by the Dutch. The basic idea of it will be familiar to anyone who has ever visited a floodplain where people haven’t had the money or inclination to try to stop floods and instead just designed their architecture around it. If you’ve ever seen a house on sticks, you get the drift.

For this contest, anyone on the internet can vote for their favorite way of preserving three different on-their-way-to-being-submerged parts of the city: the former Prince Macaroni factory, now a luxury condominium complex; 100 acres of mostly parking lot built on landfill at the edge of the Fort Point neighborhood; and Morrissey Boulevard, a six-lane traffic artery that is already on alert for closure whenever there’s a wicked tide.

Voting for the “People’s Choice Award” ends on Feb. 25. A win carries no promise that the winning proposal will actually be built; for one thing, none of the contest entries had to comply with existing zoning regulations, and for another, contests often function as more of a PR maneuver than anything else.

Right now, the project in the lead is an everything-but-the-kitchen-sink aggregation of utopian climate preparedness.

At the center rises an elevated Morrissey Boulevard draped with decorative plantings. Underneath it is a canal, stocked with what appear to be futuristic rocket-boats. Raver lights and wind turbines bristle from the honeycombed high-rises on either side.

The overall effect does not immediately strike one as Bostonian — but this is, arguably, what happens when you let the internet decide what is best for Boston. (There’s also an actual not-of-the-people jury, which will render its own verdict.)

All of this is not to say that these proposals aren’t, in their own way, completely awesome. If you love Boston (or even just feel mild schadenfreude towards it), the multitudinous schemes for its future — high-quality urban-planning porn for the next millennium — provide endless diversion.