On Saturday, voters in Austin, Texas, handed a stinging defeat to the major ride-hailing companies Uber and Lyft. The corporations had drafted a ballot proposition exempting them from some of the public safety rules governing taxis in the city and then thrown an unprecedented amount of money and clout into trying to get their way. Their hubris, it seems, rubbed Austinites the wrong way.

Despite the validity of some of their concerns, Uber and Lyft’s approach casts a negative light on the ride-hailing industry — an industry with the potential to do much good, from decreasing drunk driving to increasing mobility and reducing car dependence, thereby helping the environment.

Proposition 1 would have repealed certain requirements the city council voted to impose in December, most notably that ride-hail drivers would have to pass fingerprinting background checks, and that ride-hail cars would not be allowed to stop in traffic to pick up and drop off passengers. Taxi drivers in the city are already bound by these same rules, though with some important caveats. Prop. 1 lost, 56 to 44 percent.

What the fight is about

The city says the fingerprinting checks are necessary to ensure that drivers won’t prey on riders. Uber has drawn accusations of a high rate of sexual assault by drivers, a claim the company disputes. Austin Mayor Steven Adler (no relation to this reporter) told tech site Recode in March, “We were also hearing that fingerprinting would be helpful, from [rape crisis centers and victim advocacy organizations], who reported a sudden and dramatic increase in the number of women, mostly young women, who were victims or were coming forward as victims of sexual assault.”

Uber maintains that its system for weeding out criminals is already better than the system Austin uses for its city-licensed cab drivers. The city’s fingerprint-based background checks for cabbies only use statewide databases, so applicants with an out-of-state criminal record could slip through the cracks. Uber uses a name-based background check, but it’s national. Last fall, Uber reported that of 163 Austin taxicab drivers who applied to Uber, 53, or nearly a third, failed Uber’s background check process. Nineteen had serious convictions, such as felony assaults and drunk driving. “There is no perfect system, and we’re not saying our system is perfect,” Jaime Moore, a spokeswoman for Uber, tells Grist. “We’re willing to stand up for the credibility of our background checks.”

As to why Uber is so resistant to fingerprinting background checks, the company argues that such checks are racially biased because fingerprinting is done at the time of arrest, rather than conviction, and racist policing leads to far more unfounded arrests of African-Americans and Latinos than of whites. It’s not just ride-hail companies making this point: The Austin chapters of the NAACP and the Urban League oppose fingerprinting background checks of ride-hail drivers for this reason.

On the issue of picking up and dropping off in traffic, the ride-hail companies say that because there are no empty parking spaces in centrally located areas at busy times, there is no other way for riders to get in and out of their cars. The city says taxis are not allowed to stop in traffic and ride-hail cars shouldn’t be allowed to either. But Uber says there’s a loophole for taxis: The relevant city ordinance for taxicabs requires them to “drive to the right-hand sidewalk as nearly as possible,” but the “as nearly as possible” proviso wasn’t offered to ride-hail cars.

The Austin police and firefighters unions, for their part, were concerned enough about cars blocking traffic lanes that they opposed the Uber-backed ballot measure, contending it could threaten public safety. It’s possible that ride-hail drivers, who are often part-timers with little experience, are not as good at getting out of the way of traffic as full-time cabbies.

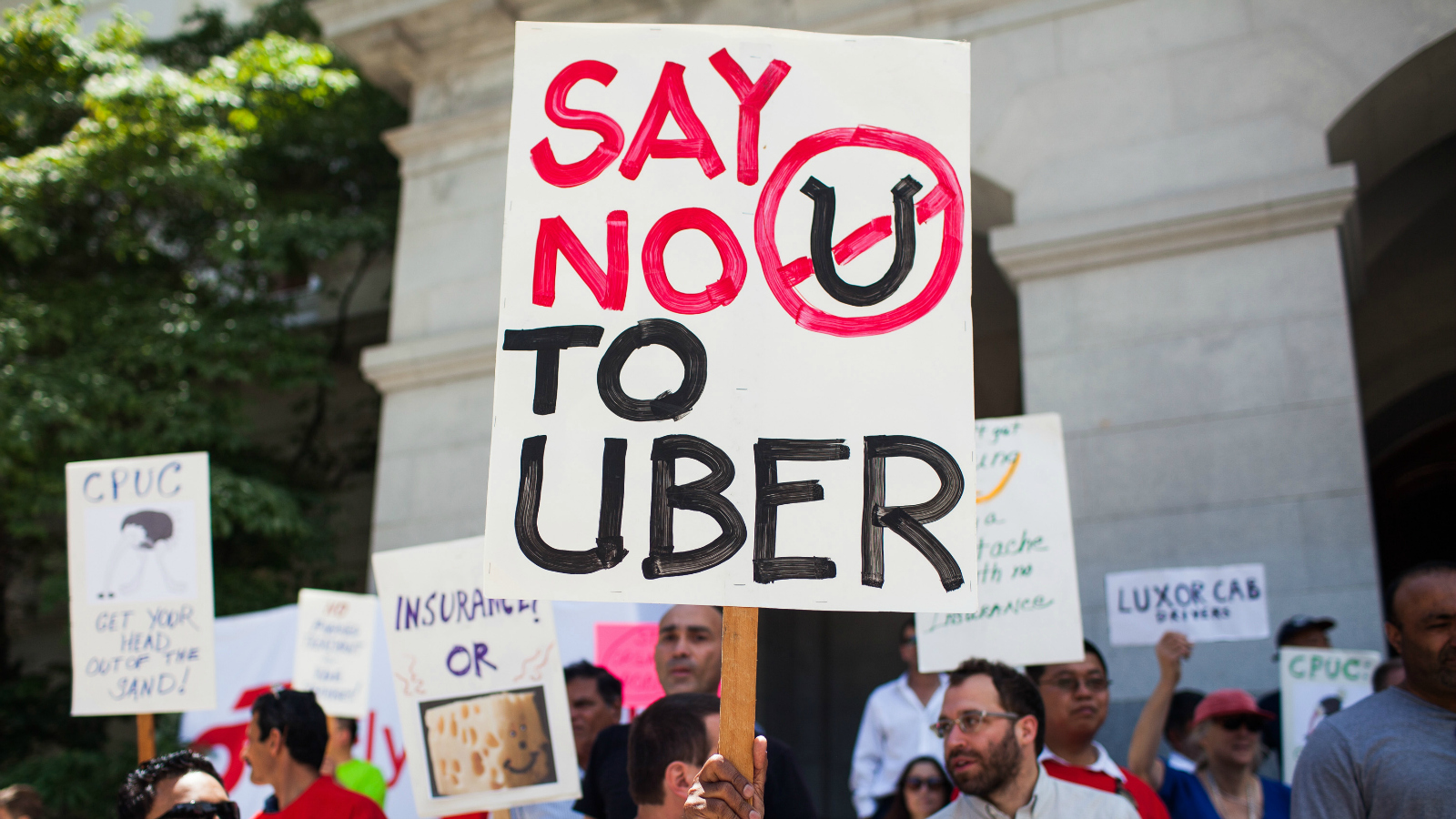

Uber and Lyft spent $9 million promoting their ballot proposition, offered free rides to the polls to their customers, and used aggressive direct outreach techniques like spamming Austinites with text messages. Their opponents called for government investigation into whether some of these activities violated campaign finance laws.

Uber and Lyft pack up and go home

The companies threatened to leave Austin unless the requirement for fingerprint background checks was dropped. On Monday, they made good on their threat and shut down operations in the city.

That is a real loss for Austin, as it lacks reliable, alternative on-demand car services. When I went there in 2013, ride-hailing hadn’t come to town yet. Taxis were hard to find and my host told me they cannot be counted on to come when called by phone. Getting to the airport early in the morning, before the buses started running, was seriously stressful and required lugging my bag to an informal taxi stand on the street in front of a major hotel.

Opponents of the ballot proposition say Uber and Lyft were trying to steamroll the city with their money and bully it by threatening to leave. “The amount of spending was shocking,” Jason Stanford, communications director for Mayor Adler, told Grist. “It was about nine times more than anyone has ever spent in a campaign in the city. There were a lot of points along the way where people perceived this not as a campaign but more of a threat.”

Adler says he wants ride-hailing services in town, just not at the expense of protecting the public. The mayor’s office says it tried negotiating more flexible solutions with Uber and Lyft, but the companies refused to come to the table. “The mayor recognized that these companies see themselves as different from taxis even though they provide a similar function,” says Stanford. “He saw an opportunity for government to innovate, as they have to in order to adjust to economic change. We have to figure out what is the proper way to regulate the sharing economy.” So, for example, instead of mandatory fingerprinting and background checks conducted by the government, the mayor proposed optional checks performed by a third party. Drivers who chose to participate would be given access to more desirable pick-up areas, such as a preferential line at the airport.

“The mayor believes that Austin needs TNCs [transportation network companies],” says Stanford. “Everyone on the city council says they are welcome to come back. [Mayor Adler] invites them to the table.” Stanford says that City Hall got tons of calls on Monday from residents who are angry that Uber and Lyft have left Austin. But, he adds, “We’ve gotten a lot of calls from other TNC providers who are interested in coming into Austin.”

And that is where Uber and Lyft overplayed their hand. There are other ride-hail companies out there, and new ones will be created. Someone will abide by the rules in Austin if the big players won’t.

Uber, especially, is used to getting its way. It entered the Austin market illegally, as it has done in many cities, and forced the city to write rules to catch up to its presence. It has flexed its political and economic muscle to intimidate cities before. Last year, it forced New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio to give up a plan to limit the number of ride-hail cars (though Uber has grudgingly acceded to fingerprint background checks in New York). In San Antonio, Uber and Lyft left because of the fingerprinting issue, only to return after striking a compromise with the city that made fingerprint checks voluntary, similar to what Adler proposes.

Uber and Lyft are widely perceived as disrespectful of the law and manipulative of the democratic process, which reinforces other concerns that progressives have about the companies. Uber is accused of exploiting drivers, and has been fighting class-action suits over the issue. One of Uber’s senior executives proposed investigating and publicizing the private lives of journalists who have been critical of the company.

In Austin, Adler contends, the companies refused to compromise. “I think the ballot initiative fight here was premature,” Adler told Recode. “I think we could have worked through this in a way that would have avoided controversy.” But the companies plowed ahead with the ballot proposition, and that triggered a backlash. “When it’s anyone versus Austin, Austin’s going to vote for Austin,” says Stanford.

If Uber and Lyft are smart, they’ll learn from their failure in Austin and work with local governments instead of trying to bully them into submission. That would be good for their companies and for the ride-hailing sector in general. But so far they have shown no sign of changing their attitude: Uber and Lyft are currently pushing for the conservative Texas state legislature to pass a bill that would undermine local regulations and let them get their way.