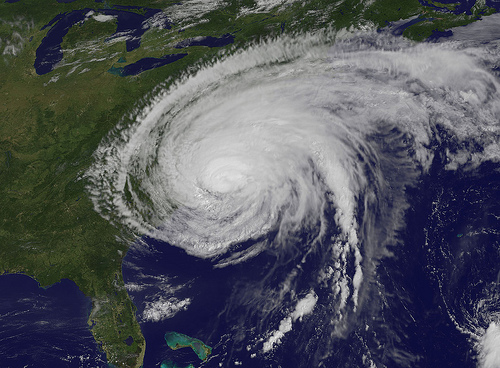

This is gonna hurt: Hurricane Irene makes landfall, Aug. 27, 2011. (Photo by NASA Goddard Space Flight Center.)

Cross-posted from the Bay Journal News Service.

In Northumberland County, Va., the Board of Supervisors has tentatively approved a massive home/resort/marina complex on Bluff Point, a marshy, wooded peninsula jutting into the Chesapeake Bay from Virginia’s lovely Northern Neck. The rural county — four stoplights, 13,000 residents — acknowledges in its master development plan that sea levels are rising, and places Bluff Point in a “conservation” zone; but after consulting experts paid for partly by the developer, the supervisors granted an “exception.”

It’s the latest example, on the shores of North America’s largest estuary, of science getting drowned out when developers wave big money at county officials craving revenue. And it’s an important story, as the Chesapeake is something of a ground zero for climate change: At the same time sea levels are rising, the land around the bay is sinking as a result of local geology. Larger-than-ever storm surges are a certainty.

Projects like the resort at Bluff Point result in a classic “lose-lose” — for the environment and for taxpayers. Instead of approving more waterfront development, the time has come to plan an orderly human retreat from more development along the watershed’s low-lying edges.

At Bluff Point, the developer may put some houses on poles as high as 8 feet in the air if needed; and that might seem reasonable, given sea level could rise about 3 feet in the next century, according to Virginia’s Climate Change Commission. But this ignores that a foot of rise, with the Chesapeake’s flattish edges, can move the Bay inland as much as 180 feet, and you can’t put roads and sewer lines on 8-foot poles.

Then there are storm surges. In 2006, Tropical Storm Ernesto caused surges along Virginia’s Bay shore of 4-5 feet, with 6-8 foot waves rolling atop that. And while there’s no proof the global warming that’s driving sea levels up will cause more storms, it’s a matter of physics that warmer water will fuel bigger ones.

Even without bigger storms, surges high enough to cause flooding at Bluff Point will occur three times a year by century’s end — and that with just a 2-foot rise in sea level. Those predictions come from Northrop Grumman, contractor for the U.S. Navy in Newport News. The company is concerned about flooding while ships are being built, a process that can take six years for an aircraft carrier. With a 3-foot sea-level rise, major floods would become 20 times as frequent.

The Bluff Point development is only one example of how our thinking about the Bay’s edges must adapt to the new reality of rising seas, says William A. “Skip” Stiles, Jr., director of the Virginia nonprofit Wetlands Watch. “If sea level is constant, your coastal region is your most valuable real estate; but with seas rising it becomes a money pit,” he says.

Wetlands Watch regularly challenges projects like Bluff Point on both ecological and fiscal grounds. Projections are that tens of thousands of acres of tidal wetlands around the Chesapeake will drown in the next century. Across the bay from Northumberland, Maryland’s Dorchester County stands to lose around 85,000 acres of marsh and forest by 2100, according to Maryland climate change experts.

The only way many wetlands could adapt would be if adjacent uplands are left undeveloped to give the marshes a chance to migrate inland as the Bay rises, Stiles says. That’s a good reason to leave places like Bluff Point in conservation zones.

Ultimately the taxpayers will pick up the bills, bailing out places like Bluff Point as flooding escalates. Taxpayer-supported federal flood insurance programs, beach replenishment programs, and the Federal Emergency Management Agency are all seeing costs soar as coastal flooding escalates. Private insurers have already pulled back from many coastal areas.

“It’s time for all these government programs to recognize times have changed,” Stiles says.

Indeed, while many Bay scientists think a 3-foot rise by 2100 is reasonable, they don’t rule out a rise up to six feet, based on the more rapid than expected melting of polar ice.

Hopes for reining in carbon dioxide and other climate change gases have dimmed with the recent refusal by the United States and China to take serious action before 2020 at the earliest. And we’ve already heated the oceans to where they will keep releasing that heat for centuries, driving sea level higher no matter how sharply greenhouse gases are reduced.

The writing is on the wall. It’s time to sound the retreat.