Of all the subjects that haunt the climate conversation, none is so vexed as growth.

The details are complex, but the dilemma is simple: Growth seems to improve humanity’s quality of life and drive ecological overshoot at the same time.

On one hand, economic growth leads to poverty reduction, better health, technological innovation, and (local) environmental improvement. On the other hand, it has pushed us into the red zone on climate and a number of other global ecological indicators. Humanity’s lot steadily improves while biophysical systems are pushed closer to the edge. It’s a sticky wicket. Pro-growth and anti-growth types often seem involved in entirely separate conversations, passing like ships in the night. How can we reconcile their perspectives?

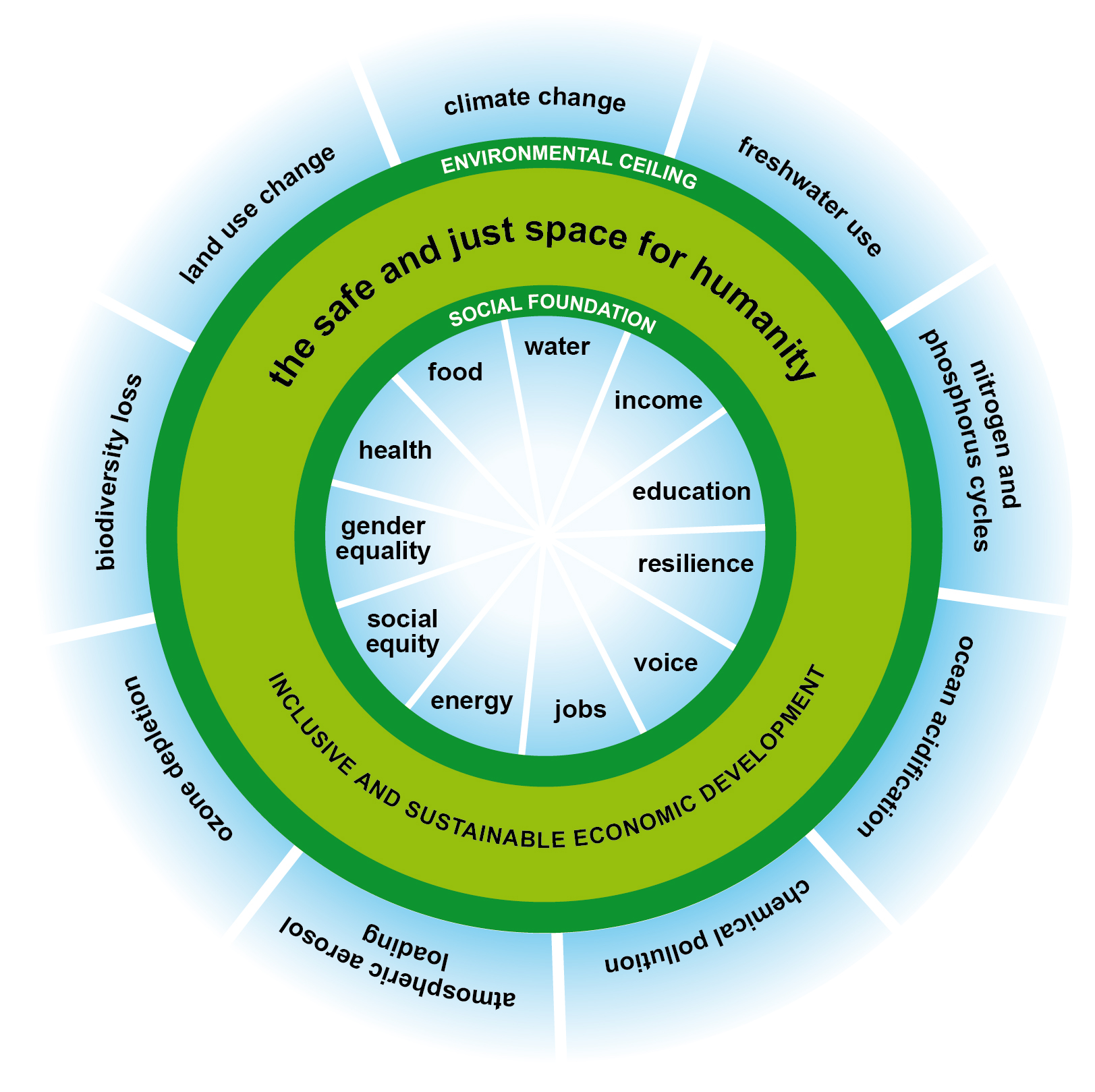

Last week, researcher Kate Raworth of Oxfam International proposed a new framework for understanding how human development and ecological boundaries fit together. Happily, it’s a doughnut. Here’s what it looks like:

So what are we looking at?

Around the outside ring are nine biophysical systems, identified by a team of scientists in a seminal study in Nature in 2009. (I wrote it up here.) Each system is involved in keeping planetary conditions in roughly the stable equilibrium they’ve been in throughout the Holocene, during which humanity developed agriculture and iPods. For each system, there is an “environmental ceiling” past which large and possibly irreversible changes may be triggered.

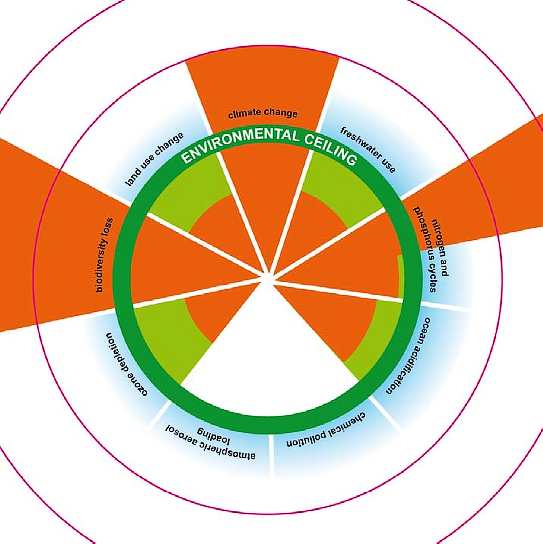

Here’s how Raworth’s discussion paper visualizes what the scientists found:

We are past the threshold of safety on three and heading toward it on several others. Yikes.

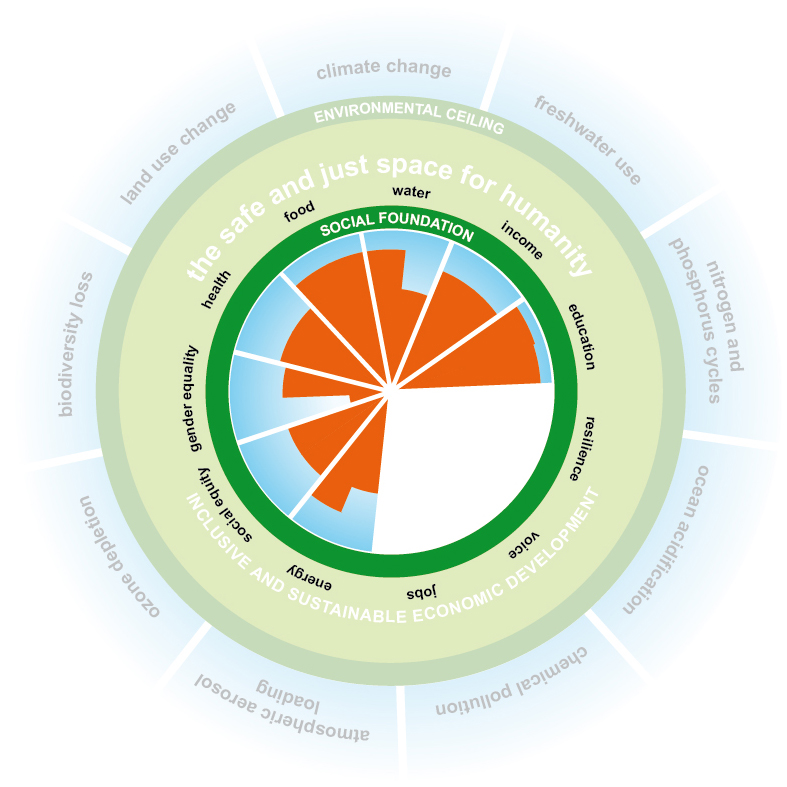

Around the inside of the doughnut are 11 social indicators, which form a “social foundation.” They are drawn from countries’ submissions to the Rio+20 conference on sustainable development. The bad news, says Raworth, is that we’re not doing great on these either. She attempts to identify clear metrics for eight of the 11, and finds that we’re not yet up to the doughnut zone on any of them. We’ve got a long way to go to lift the world’s expected 9 billion people up to a minimum standard of health and dignity:

Raworth’s insight is that the goal of policy should be to get in the doughnut (which also happens to look quite a bit like a life preserver). In the “safe and just space for humanity,” every human has access to at least a minimum level of dignity and health, but ecological overshoot is avoided.

Obviously this way of thinking about it doesn’t make the task any easier, but it does make the nature of the task clearer — far clearer than a simple “growth vs. no growth” debate. Good policy will raise up social indicators into the doughnut without pushing ecological indicators out of it, or vice versa. Bad policy will push one side at the expense of the other.

You might be thinking: It’s fine to frame things that way, but it’s just another way of revealing that our task is impossible! The doughnut is a null set. There’s no way for 9 billion people to be middle class without driving the planet off a cliff.

Raworth addresses this a bit. She notes:

• Food: Meeting the calorie needs of the 13% of the world’s population facing hunger would require just 1% of the current global food supply

• Energy: Bringing electricity to the 19% of people who currently lack it could be achieved with less than a 1% increase in global CO2 emissions

• Income: Ending income poverty for the 21% of people who live on less than $1.25 a day would require just 0.2% of global income.

This is interesting, but I think it rather undersells the difficulty of the matter. If you were God and you could gather up resources in a big pile and parcel them out, you could probably get 9 billion people in a decent state. But political economy matters. Attempts at wholesale redistribution haven’t worked out very well in the real world. Virtually all gains for the developing poor these days come in the context of economic growth that disproportionately benefits the wealthy and drives ecological overshoot. It might be possible in theory to have growth in living standards without ecological degradation, but thus far no country has pulled it off.

Anyway, that’s a big topic, for another time. For now, I’m just taken by Raworth’s framework as a way of thinking about growth within ecological systems — not “growth good” or “growth bad,” but what kind of growth and to whose benefit?

Also, I want a “get in the doughnut” T-shirt.

——

Here’s Raworth introducing the framework: