Cross-posted from Climate Progress.

Back in November, GE’s TXCHNOLOGIST blog pointed out that climate change “could ruin Texas football,” indeed all southern U.S. football:

The effects of climate change, so far, have been most noticeable in Texas, where a terrible drought has dried up football fields in small towns that used to look forward to Friday nights above all. But climate change will have a terrible effect on communities throughout the cradle of football in the Southern and plains states.

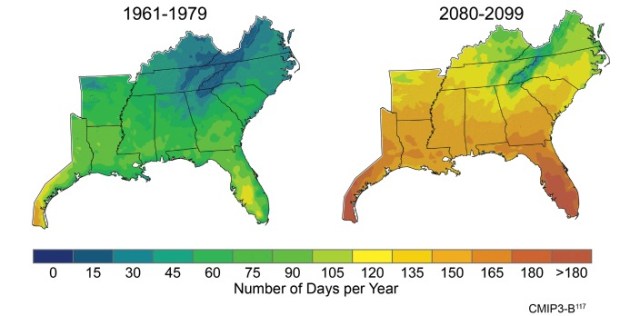

Florida, Alabama, Louisiana, Texas. The home states of the last five college football champions? Yes. But these are also states that are projected to experience 150-180 days a year with peak temperatures over 90 degrees Fahrenheit by the final decades of the 21st century. That’s almost six months of the year. In parts of Florida and Texas the number is likely to exceed 180 days a year. Not only will the high temperatures be hotter, the lows will also be higher, so there will be less relief from the sultry conditions. This warming effect will have devastating effects on the ecology and economies of these area and make watching and playing football outdoors almost unbearable. [Emphasis mine.]

This is going to come as a big shock to the football fans throughout the region, many of whom have been heavily disinformed by their politicians and favorite media outlets.

Indeed, it is the conservative southern U.S., especially the south central and southeast, who have led the way in blocking serious climate action, as it were, making yesterday’s worst-case scenario into today’s likely outcome.

Photo by Gator.

I’m a football fan, born and raised in New York State. Ironically, it looks like warming is going to make football more of a northern U.S. game — though that will be among the least consequential of the myriad global warming impacts.

GE’s blog points out a key danger of the ever-worsening heat and heat waves: “Players will run increasing risk of hyperthermia.” Andrew Grundstein, of the Climatology Research Laboratory at the University of Georgia, has analyzed heat-related deaths of football players since 1980. In August, he explained his findings in a press call and pointed out some of his remarkable findings, including the fact that “the conventional wisdom that coaches can reduce the risk by practicing in the morning is inaccurate”:

- The death rate has increased since the mid-1990s

- Most of the deaths occurred early in the August practice period, with nearly 25 percent happening during the first three days of practice

- The overwhelming majority — 86 percent — of those who died were linemen

- Most of the deaths occurred in the eastern half of the United States

“Many coaches assume that morning practices are safer because they are cooler,” [said Grundstein]. “But almost 60 percent of the deaths came after exposure during morning practices. The mornings may be cooler, but they also may be more humid which can increase the heat stress.”

Deke Arndt, chief of the Climate Monitoring Branch of NOAA’s National Climatic Data Center, said that based on climate change projections, record temperatures and intense heat waves are likely to occur more frequently in the future. He also pointed out that many U.S. cities have set records for overnight temperatures this summer, which often is associated with higher humidity.

“Overnight temperatures don’t get as much attention as record highs,” Arndt said, “but in recent summers, we’ve been seeing that extremes in warmer low temperatures have been outpacing those for afternoon temperatures in terms of setting records.”

Last week, the Centers for Disease Control reported that an average of 6,000 people go to emergency rooms every year for heat-related illnesses during sports or recreational activities. The highest percentage of them are males between the ages of 15 and 19.

The good news is many of the deaths are preventable:

“This is not just about making sure players drink a lot of liquids,” said Michael Bergeron, director of the National Institute for Athletic Health and Performance at Sanford Health, and one of the country’s leading authorities on how young athletes are affected by exercising in hot weather. “It’s also about making sure they have the time to get acclimated to practicing under these conditions and adjusting the work-to-rest ratio appropriately.

“Even when athletes are well-hydrated, if it’s hot enough and you go hard enough, people can die,” added Bergeron, who has written guidelines for what coaches can do to reduce the risks to their players. “The bottom line is, heat-related deaths on the athletic field are preventable.”

The bad news is, the climate is just going to get much, much worse if we keep listening to the disinformers. Indeed, the GE blog points out:

Grass fields will turn to dust, synthetic fields will be too hot to touch

The near-Biblical drought that has gripped Texas in recent years has parched dozens, maybe even hundreds, of grass football fields. This is a preview of things to come. Drought and water scarcity will likely become more commonplace throughout football’s heartland, meaning more natural turf fields will turn to dust. And while artificial turf presents a plausible alternative to natural turf, synthetic fields are expensive and can cook to 50-100 degrees Fahrenheit hotter than the air temperature on hot days (natural turf fields rarely exceed 100 degrees). Artificial turf can be irrigated to bring temperatures down but surface temperatures rebound quickly, according to studies. And irrigating does not address water scarcity problems.

Ouch, literally.

The link goes to a SportsTurf article, “Is there any way to cool synthetic turf?,” which concludes:

What do these results tell us? As of right now, it is obvious that there is no “magic bullet” available to dramatically lower the surface temperature of synthetic turf. Reductions of five or even ten degrees offer little comfort when temperatures can still exceed 150 degrees F. Until temperatures can be reduced by at least 20-30 degrees for an extended period of time, surface temperature will remain a major issue on synthetic turf fields.

It’s worth noting that the chart at the top of days per year above 90 degrees F is the IPCC A2 scenario (about 850 parts per million [ppm] atmospheric concentrations of CO2 in 2100). On our current emissions path, we are headed toward A1FI, 1,000 ppm (see here). In a March 2010 presentation, climate scientist Katharine Hayhoe has a figure of what the A1FI would mean:

Are you ready for some 100 degrees F football, southern states?

It is, of course, unclear whether people will still want to play football when the land has turned to dust and the nation and the world are suffering through multiple horrific impacts.

“Bread and circuses” — panem et circenses — goes the old saying. Hmm. Maybe the future of sports is The Hunger Games.