Fire and a vast oil spill, on top of one of the globe’s most productive fisheries. Photo: U.S. Coast Guard

Fire and a vast oil spill, on top of one of the globe’s most productive fisheries. Photo: U.S. Coast Guard

The Gulf of Mexico is a magnificent resource: a kind of natural engine for the production of wild, highly nutritious foodstuff. Here’s how the EPA describes it:

Gulf fisheries are some of the most productive in the world. In 2008 according to the National Marine Fisheries Service, the commercial fish and shellfish harvest from the five U.S. Gulf states was estimated to be 1.3 billion pounds valued at $661 million. The Gulf also contains four of the top seven fishing ports in the nation by weight. The Gulf of Mexico has eight of the top twenty fishing ports in the nation by dollar value.

According to the EPA, the Gulf is the home of 59 percent of U.S. oyster production. Nearly three-quarters of wild shrimp harvested in the United States call it home. It is a major breeding ground for some of the globe’s most prized and endangered fish, including bluefin tuna, snapper, and grouper.

It would be a wise policy to protect the Gulf, to nurture the health of its ecosytems, to leave it at least as productive as we found it for the next generations. As climate change proceeds apace and population grows, sources of cheap, low-input, top-quality food will be increasingly precious.

So, how are we doing? As I write this, oil is gushing into the Gulf at the rate of 5,000 barrels per day, 5,000 feet below the water’s surface, The New York Times reports. Above the surface, an oil slick with a circumference of 600 miles is lurching along, lashed by wind toward the coasts.

By Friday, it will have reached Louisiana’s wildlife-rich coast. And according to MarketWatch, “Beaches in Alabama and Mississippi are also threatened, and, if the spill spreads into the Gulf’s ‘Loop Current,’ it could devastate coastlines as far away as southeastern Florida.”

For fisheries, the situation is atrocious. Direct contact with high oil concentrations kill fish quickly. But low-concentration contact can have horrible impacts, too. According to Greenpeace:

Even when the oil does not kill, it can have more subtle and long-lasting negative effects. For example, it can damage fish eggs, larva and young — wiping out generations. It also can bio-accumulate up through the food chain as predators (including humans) eat numbers of fish (or other wildlife) that have sub-lethal amounts of oil stored in their bodies.

Tragically, now seems to be a particularly awful time for a massive spill. On the Oceana blog, Matt Niemerski writes:

[S]cientists say this is a critical time for bird life in the region because it is peak nesting and migration time for hundreds of species. Endangered sea turtles are beginning to lay their eggs along beaches in the area and bluefin tuna are spawning right now. Whales, dolphins and sea turtles are also at risk because they could inhale oil when they come to the surface to breathe.

What started with a human tragedy and suspected tragic loss of 11 lives on April 21, now appears to be unfolding into one of the worst environmental disasters in U.S. history.

And that’s not all

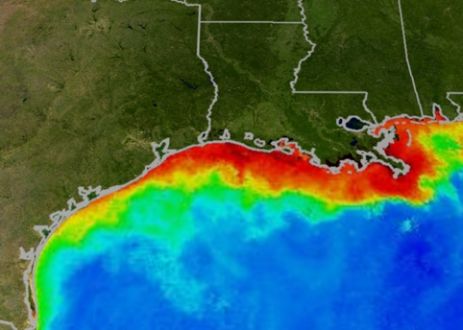

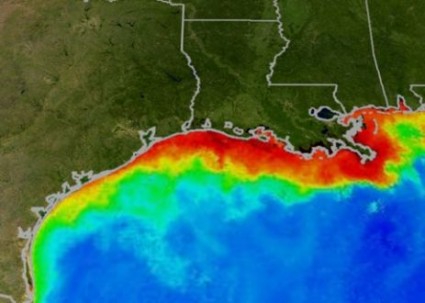

A satellite view of the Gulf. In the red areas, a vast, nitrogen-fed algae bloom has risen, blotting out most sea life underneath.Photo: NASA

A satellite view of the Gulf. In the red areas, a vast, nitrogen-fed algae bloom has risen, blotting out most sea life underneath.Photo: NASA

It should be remembered that oil drilling is not the only human activity that imperils this vital ecosystem. Every year, millions of tons of synthetic nitrogen and mined phosphorous leach from Midwestern farm fields and into streams that drain into the Mississippi. The great river deposits those agrichemicals right into the Gulf, where they feed a 7,000-square-mile algae bloom that sucks up oxygen and snuffs out sea life underneath.

The bulk of this vast Dead Zone’s rogue nutrients comes from the growing of corn, our nation’s largest farm crop. Half of the corn crop ends up in feedlots, feeding cows, chicken, and pigs stuffed together in pollution-spewing, factory-style feedlots.

The federal government has mounted an effort to stem the flow of fertilizer from farms to the Gulf. But policies that encourage maximum production of corn — including mandates and tax breaks for corn ethanol — overwhelm those gestures. Thus the Dead Zone has become a routine fact of life in the Gulf, the cost of doing business for a food system that prizes cheapness and industry profit above all else. As the writer Richard Manning puts it in the winter 2004 American Scholar (unavailable online):

Already, the Dead Zone has seriously damaged what was once a productive fishery, meaning that a high-quality source of low-cost protein is being sacrificed so that a source of low-quality, high-input subsidized protein can blanket the Upper Midwest.

The government-generated boom in corn-based ethanol plays its role, too. Five years ago, just 13 percent of the corn crop went into ethanol factories. Today, a third does; by 2015, if government mandates hold, fully one-half will. Already, increased demand from ethanol is taking its toll on the Gulf.

Back in 2008, after ethanol production had soared, the Louisiana Universities Marine Consortium reported, “The nitrogen loading to the Gulf of Mexico in May of this year was 37 percent higher than 2007 and the highest since measurements began in 1970.” The group added: “The intensive farming of more land, including crops used for biofuels, has definitely contributed to this high nitrogen loading rate.”

Thus like the oil spill, the Dead Zone owes some of its existence to our reliance on auto transportation.

At this time of year, fertilizer runoff is streaming into the Gulf, and the algae bloom is just beginning to do its dirty work. Now, adding to the routine depredations of the agricultural runoff, we have what’s looking likely to emerge as the nation’s largest oil spill ever.

Rather than protect the Gulf, we seem determined to destroy it in pursuit of cheap car fuel and cheap meat. Is it too late to reverse course?