This is part of a series of posts on distributed renewable energy that will be posted to Grist. It originally appeared on Energy Self-Reliant States, a resource of the Institute for Local Self-Reliance’s New Rules Project.

When we released our report on community solar power last month, we expected a few comments on the grades we gave to the nine featured community solar projects. We also generated a really robust conversation about the location (on buildings or on the ground) of community solar PV projects and made a disheartening discovery about the cost of roof repairs when a solar PV array is present.

When we released our report on community solar power last month, we expected a few comments on the grades we gave to the nine featured community solar projects. We also generated a really robust conversation about the location (on buildings or on the ground) of community solar PV projects and made a disheartening discovery about the cost of roof repairs when a solar PV array is present.

In the report, our criteria for solar PV location gave high marks for rooftop solar PV systems because of their use of existing infrastructure, lower marks for ground-mounted systems in brownfields, and the lowest grades for greenfield systems. In one particular case, we gave a ‘C’ grade to the Clean Energy Collective’s (CEC) project because while it used otherwise unusable land near a sewage treatment plant, it was still ground-mounted.

The response to their ‘C’ grade made us reevaluate our grading system. On reflection, there are three major considerations for the location of a community solar (or any distributed renewable energy) project.

Location criteria for community solar

- Preservation of open space

- Use of existing grid infrastructure

- Lifetime cost for participants

Open space

The open space issue cannot be ignored, as demonstrated by the opposition to centralized concentrating solar thermal power and solar PV power plants in the Mojave Desert and San Luis Valley in Colorado. Projects that use rooftops will rarely encounter resistance on environmental grounds (although there can be issues with historic districts). From the perspective of open space, there is still a higher value in a rooftop project than a ground-mounted one.

Existing grid infrastructure

The issue of existing grid infrastructure is not as clear cut. In general, distributed solar PV projects minimize the need for new grid infrastructure by plugging into the grid at low voltages and in a variety of places.

Rooftop solar would seem to have an advantage in this. With few exceptions, a rooftop solar PV system can easily interconnect through the building’s grid connection. A rooftop solar PV system doesn’t change the capacity required by the local grid connection because net metering limits typically mean that no one installs a system that produces more than the building consumers.

But our error was to assume that ground-mounted systems would not take advantage of existing infrastructure, as well. In fact, the Clean Energy Collective solar project connects to existing infrastructure at an adjacent sewage treatment plant. Several other community solar projects in the report were constructed by utilities and presumably built next to existing substations where the new generation could easily be absorbed into the local grid. In other words, we should have graded this location criteria separately from the open space issue.

Lifetime costs

The third issue — and one we’d never considered — is that rooftop PV systems may have to be removed and reinstalled if the roof needs replacement or repairs. While PV systems typically lose a small portion of their potential output (< 1 percent) each year, the systems can operate for decades, far longer than the typical residential or commercial roof (20-25 years in Minnesota). In other words, there’s likely to be one roof replacement during the life of a PV system.

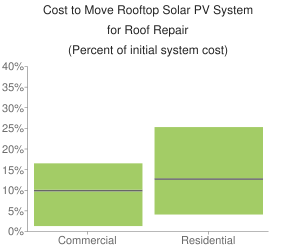

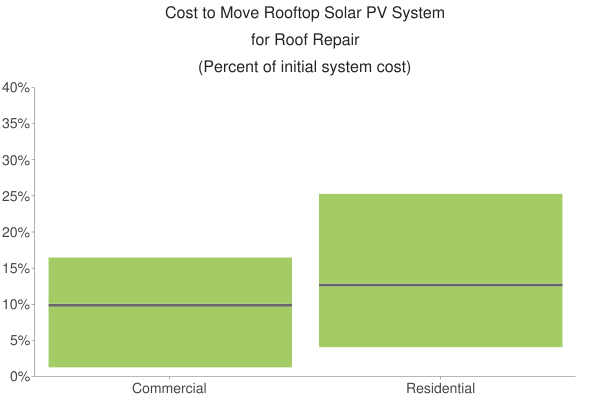

Reinstalling a residential rooftop PV system could cost $6,250 or 25 percent of the installed cost of the system. In our investigation, we found that moving residential PV systems to accommodate a roof replacement could cost as much as 25 percent of the initial system cost (and over 35 percent of the net cost after the application of the 30 percent federal tax credit). Moving systems on a commercial roof was less expensive, on the order of 15 percent of initial installed cost (around 25 percent of the system cost after the tax credit).

The chart to the right illustrates the range of costs we found relative to an initial installed cost of $5.00 per watt for commercial and residential PV systems.

The chart to the right illustrates the range of costs we found relative to an initial installed cost of $5.00 per watt for commercial and residential PV systems.

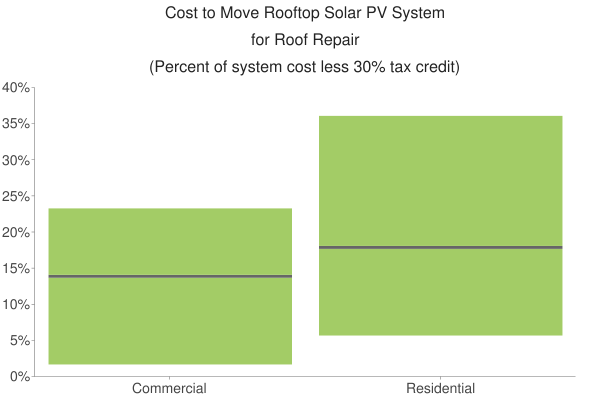

But this chart is somewhat disingenuous, because solar PV owners never pay the full installed cost. Instead, there are a slew of tax credits and rebates that reduce this initial price. The next chart shows these roof repair reinstallation costs relative to the net cost after the 30 percent federal tax credit.

But this chart is somewhat disingenuous, because solar PV owners never pay the full installed cost. Instead, there are a slew of tax credits and rebates that reduce this initial price. The next chart shows these roof repair reinstallation costs relative to the net cost after the 30 percent federal tax credit.

The cost issue is also complicated by various ownership arrangements. If the building owner also owns the array, the cost of moving the PV system is their responsibility. But what if they lease the solar array? Does the leasing company bear the cost of system safety when the roof is repaired or replaced or is it still the responsibility of the building owner? Will that cost be assessed when the roof is repaired or escrowed from the start of the project?

A CEC representative noted, “I guarantee you that a building owner (lessee) will never sign a long term lease that requires them to pay the costs of reinstalling a system after roof repairs, etc.” If CEC’s recently completed 77 kW community solar array had been built on a rooftop and required a move, the cost to its individual investors would likely be around $2,000, increasing the upfront cost for those individuals by nearly 30 percent. In addition, CEC couldn’t have offered the utility or its customers a 50-year service level agreement.

Conclusion: Location is complicated

Obviously, there’s much more to the ground vs. rooftop issue than meets the eye, from interconnections to roof repairs. Look for a transformation in our Community Solar Report in the next few weeks reflecting on this complex issue.