As the international community continues to struggle to advance a global climate change agenda, new kinds of climate actors are increasingly working to pick up the slack. Hopes are high that cities, regional coalitions, and businesses — or non-state and sub-national actors, in wonk-speak — can make up for lost ground, and lead countries toward more ambitious action.

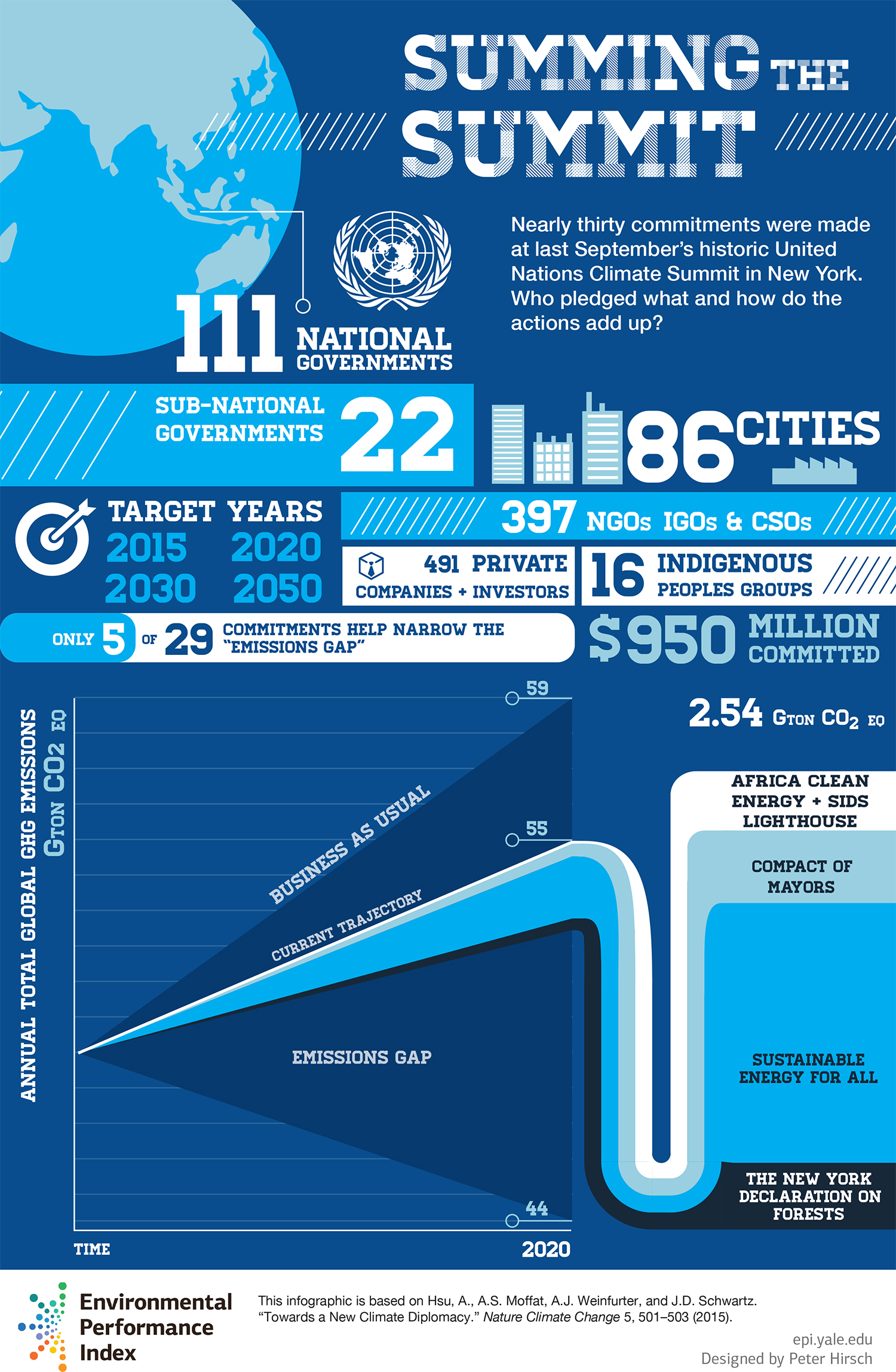

One early indication of what a hybrid approach that includes multiple actors might look like came last September, at U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon’s Climate Summit in New York City (hereby referred to as the “Summit”). On Sept. 23, 2014, the Summit convened Fortune 500 CEOs, indigenous communities, and more than 350 civil society leaders, alongside 125 heads of state. Together, they produced 29 collaborative, multi-stakeholder action statements and plans to fight climate change.

These plans are powerful symbols of the climate movement’s broadening base, and the groundswell of pioneering solutions to climate change. But do they add up to real reductions in planet-warming greenhouse gases?

Summing up the summit

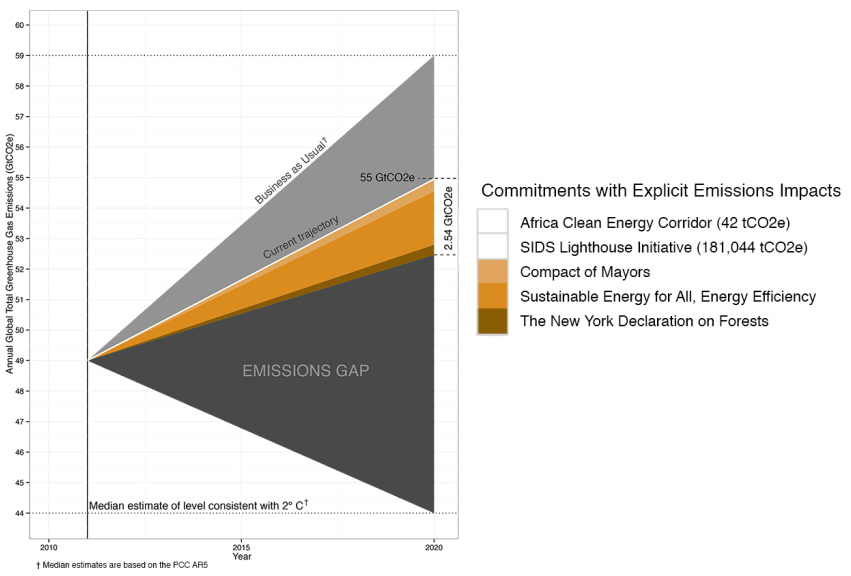

To answer this question, the Yale Environmental Performance Index team set out to sum up the Summit. A newly published piece in Nature Climate Change details the results of our analysis. We found that the Summit’s plans could make a notable dent in emissions. Together, they would take a 2.5 gigatonne bite out of the 8–10 gigatonne gap that separates the annual CO2 reductions countries have pledged from the amount of reductions needed by 2020 to contain global temperature rise to 2 degrees Celsius. This 2-degree target represents scientists’ best estimate of the warming the planet can sustain before triggering the most damaging — and costly — impacts of global warming.

So while the Summit’s pledges don’t amount to a silver bullet, they could play an important role in staving off the worst impacts of climate change.

A double-edged sword

Of course, the Summit’s impact depends on the implementation of its commitments, which remains uncertain. The Summit’s flexibility may prove to be a double-edged sword. On one hand, its open-ended nature helped draw new kinds of participants, and catalyze new types of coalitions. However, without a common set of standards, the plans’ strength and specificity vary widely.

The Summit’s commitments mirror its inclusive, come-one-come-all style. They encompass eight overarching action areas, ranging from forests to transportation to climate finance. One hundred and eleven national governments, 22 sub-national governments, 85 cities, 358 civil society organizations, 481 private companies and investors, and 16 indigenous peoples joined one or more of these pledges. Their geographic focus is equally diverse; one plan hones in on Africa’s clean energy potential, while others stretch across cities, industries, or regions.

It was not easy to quantify the impacts of these impressive calls for action. The plans fall across a spectrum. Some, like the SIDS Lighthouses Initiative, leverage existing partnerships and capacity toward even more ambitious action. This commitment to foster renewable energy development in small island nations includes a seven-point, five-year outline for implementation. In contrast, the Global Investors Action Statement paints with a broader brush, noting the need for “stronger political leadership and more ambitious policies” to support carbon-resilient investments. This commitment, and others like it, focus more on establishing a consensus for change than on realizing it.

Across the board, many plans lack detailed information about their emission reduction targets and timelines, or their intentions for monitoring progress. Out of 29 action statements or commitments, only eight contain enough information to evaluate their ability to lower emissions. We narrowed this number down to five by discounting plans that might overlap with preexisting national plans and efforts.

Hazy funding strategies could also create stumbling blocks. Just two of the 29 plans include explicit financial commitments. Only one plan — the much-lauded New York Declaration on Forests, which aims to halve deforestation by 2030 — includes both an explicit funding source and a clear and measurable target.

Building a bigger tent

To deliver on the momentum they have brought to the climate dialogue, the pledges will need to resolve the tension between flexibility and accountability. Defining clear criteria for meaningful mitigation, adaptation, or financing commitments is crucial to understanding and calculating the impact of these pledges. At the same time, events like the Summit must walk a fine line. Guidelines need to ensure accountability without discouraging buy-in from participants worried about higher costs or high-profile scrutiny.

This balancing act echoes larger questions about the role of new kinds of actors in a complex climate landscape. Countries often rely on businesses, civil society organizations, and sub-national governments, such as cities, states, and provinces, to implement their emission-reduction efforts. Teasing out the impact of new climate actors will require strategies that ensure their reductions are not counted twice. Put another way, harnessing the potential of new climate actors also means shaking up the ways national governments pledge and report on their progress.

As the December 2015 U.N. Climate Change Conference in Paris approaches, questions about whether and how to integrate these kinds of non-state actors into national strategies loom especially large. This landmark meeting, where the international community will negotiate a new climate change agreement, gives countries unprecedented leeway to set their own targets and metrics, via Intended Nationally Determined Contributions (INDCs).

This flexibility could enable governments to leverage on-the-ground activity to support national programs and goals. However, if INDCs offer vague or incomplete targets, they could also make it more difficult to identify overlaps between national and non-state efforts, or to pinpoint gaps that non-state actors could help to fill.

New narratives

Despite the challenges of syncing non-state and national efforts, this coordination is crucial to the success of both. Non-state actors can play a pivotal role in “wedging the gap” between climate change goals and national pledges. But it will still be critical for national governments to take the lead in ensuring that their own commitments are ambitious and credible. Specifying the exact impact of city, state, and industry contributions will push countries to keep up, and clarify the size of the gap that all climate actors must work to close.

In this, and in many other instances, the Climate Summit challenged the narratives that typically surround new forms of climate action. It could be tempting to cast these efforts as a crucial path away from the stalled international response to climate change, but they aren’t ambitious or reliable enough to replace national actions. On the other hand, some people argue that the kinds of plans hatched at the Summit are just hot air — that a lack of firm metrics fails to weed out greenwashing or flag double-counting. Our analysis indicates that, despite these doubts, these plans could have real impact. The Summit embodies the potential rewards and risks of new kinds of climate action, and reminds us that the process of structuring these commitments is still very much in flux.

A great deal of work remains before the benefits of a bigger tent are realized. Figuring out how to define and measure non-state actions will test, strain, and possibly advance traditional methods of climate accounting. Despite the sticky logistical and political obstacles they face, non-state actors are powerful partners for addressing global warming. Their contributions should not be thrown out just because of the difficulty of measuring them.

—–

Amy Weinfurter is a 2015 Masters of Environmental Management graduate of the Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies. She is currently a research analyst at the Yale Environmental Performance Index.