Carbon offset programs are typically billed as an undo button for climate-harmful activities. You can, for example, pay extra for an airline ticket in order to fund the planting of trees to neutralize the harmful impact of the emissions generated by your flight.

It’s a well-intentioned idea, but it doesn’t always work. Offset programs are not well regulated, are plagued by accounting errors like double counting, and sometimes give credit where they arguably shouldn’t — for instance, for forest management activities that would be done whether or not the program existed. Then there is the moral hazard question: Might offset schemes encourage more emissions by making people and companies feel that they have permission to pollute?

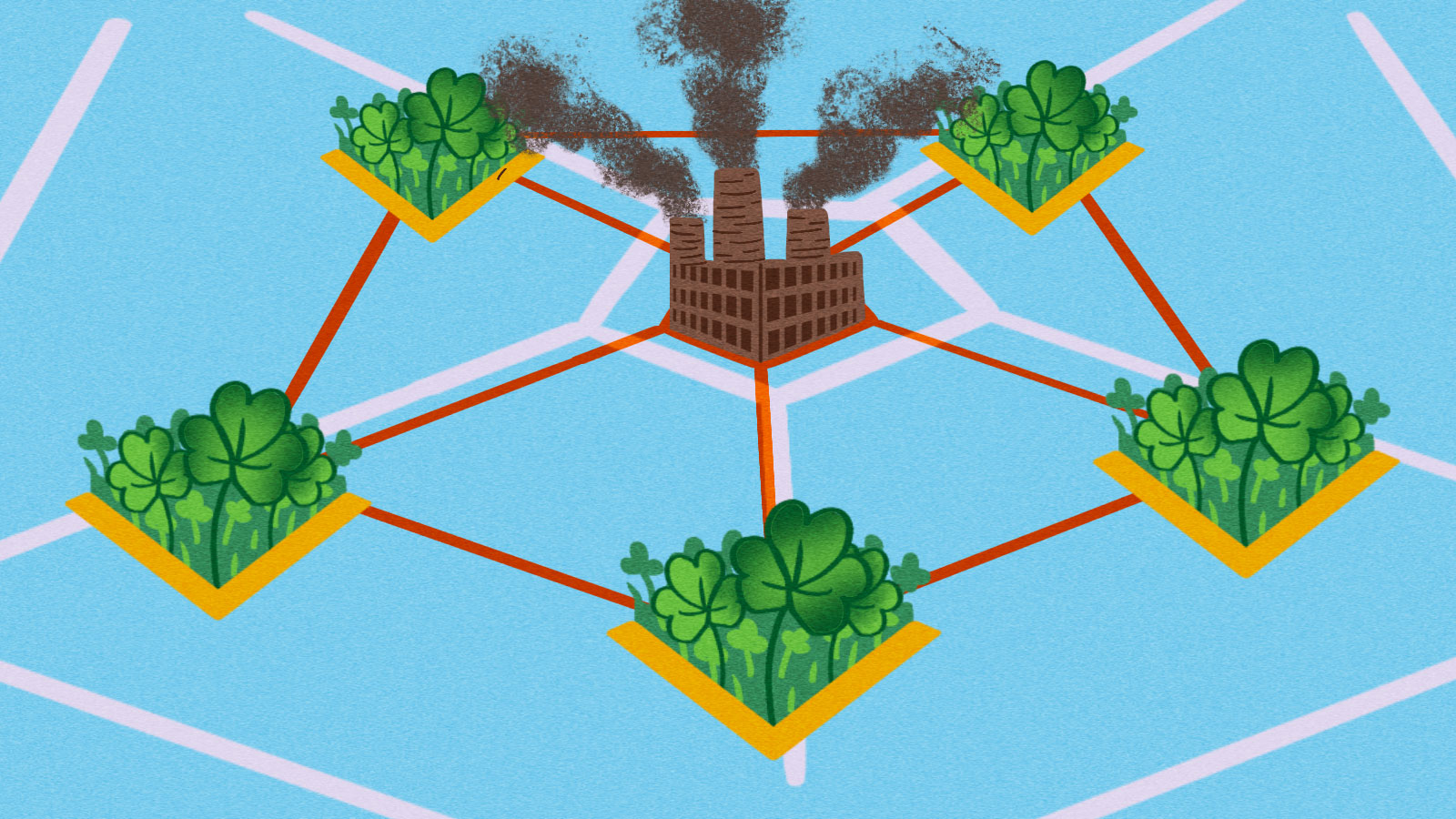

The Seattle-based company Nori is trying to overcome these concerns. It is the first marketplace to sell offsets based exclusively on removing carbon dioxide from the air — and it’s doing it using blockchain technology. Nori will work with partners to verify that carbon’s been pulled out of the atmosphere and issue a Carbon Removal Certificate or CRC for every ton of CO2 sucked out of the atmosphere. Each of these CRCs can be exchanged for a Nori token, a form of cryptocurrency. Nori tokens will have a value that fluctuates with market demand, much as other commodities do. Like bitcoin, Nori tokens can be redeemed for cash or used as currency with any merchants that decide to accept it. While other companies are applying blockchain technology to various aspects of climate change — as a marketplace for carbon credits, for instance — only Nori is applying it to carbon removal.

Blockchain technology may be particularly well suited to address some of the problems that have plagued other offset programs. Originally developed for the Bitcoin cryptocurrency, a blockchain is “a shared and continually reconciled database.” Every one of the thousands of nodes on the blockchain network has a full copy of this database or ledger. This leads to inherent transparency, integrity, and security. Nori CEO Paul Gambill says he built his service around a blockchain because “it’s a provable distributed ledger that addresses double-counting and establishes unambiguous ownership.” (Editor’s note: Gambill is in a personal relationship with a Grist staffer who played no role in assigning or editing this article.)

Nori’s decision to link carbon credits to the blockchain may raise some eyebrows. Blockchain technology can be very energy-intensive — a recent study put Bitcoin’s total carbon footprint on par with that of Las Vegas.However, newer, more efficient versions of blockchain technology are in development, and Gambill told Grist that Nori will be transitioning to the more energy-efficient proof of stake (PoS) technology as it becomes available.

Nori also aims to avoid the trap of selling offsets based on trees that were never really in danger of being burned or cut down in the first place. Nori describes itself as “the only market that deals exclusively in removing past emissions” from the atmosphere — which it’s doing by investing in soil carbon sequestration.

Research has shown that certain agricultural practices, such as no-till farming and the use of cover crops, can pull carbon from the air, while providing a number of additional benefits to soil health, such as improved fertility and water-holding capacity. Scientists now recognize that these beneficial effects largely come from communities of microbes that live in the soil and help nourish the plants. Agricultural practices such as plowing and applying chemicals have decimated these soil communities. In fact, much of the carbon in our atmosphere today came from soils that were disturbed by modern farming practices.

But how can we measure the amount of carbon being pulled out of the air with these agricultural practices? Nori is using the COMET-Farm model program housed at Colorado State University. COMET, which stands for “carbon management and emissions tool,” is an analytical platform developed by soil ecologist Keith Paustian. The model uses location-specific data on soil type provided by U.S. Department of Agriculture, weather models, and an ecosystem simulation model — along with data provided by farmers — to compute the total amount of carbon captured through sequestration. Nori will use that data to pay farmers for the carbon their soil removes from the air and issue corresponding certificates. Most current research indicates that if optimal practices are utilized, approximately one to two tons of carbon per acre can be sequestered, though higher levels might be possible.

Nori’s business model can help “expand the conversation about what measures we use to determine the productivity of the system” of a farm, said Rachel Stroer, the chief strategy officer at the Land Institute, an agricultural research organization based in Salina, Kansas. For instance, she explained, it can help with answering critical questions, like, “How do we compensate the grower for the value they are providing to the future of food production?”

Through a “lightning sale” that began earlier this month, Nori is offering the opportunity for anyone to pay for soil carbon sequestration to happen — to help provide short term financial incentives for practices that will pay off in the long term. Maryland-based Harborview Farms, located on the Delmarva Peninsula, is Nori’s initial partner in the effort, earning income based on the carbon it’s pulling from the air.

The biggest challenge for Nori will be the verification process. While the COMET model was developed under USDA guidance and is the best available, it’s not perfect. “There is still the complexity of the biological systems, the variable climates, so we can’t be entirely sure of exactly how much carbon is sequestered in the soil in each year, or how long it persists,” said Francesca Cotrufo, a professor of soil and crop science at Colorado State. In order to improve that accuracy going forward, a collaborative soil carbon monitoring network is in the works.

There are also questions about whether soil carbon sequestration can scale. Nori CEO Paul Gambill told Grist that the company is in discussions with a number of Big Ag companies, though he declined to reveal any names. Incidentally, General Mills recently committed to “bring regenerative agricultural practices,” which include measures such as no-till farming and cover cropping to one million acres by 2030. Soil carbon sequestration, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, is the most cost-effective way to pull carbon from the atmosphere. Once Nori’s soil carbon sequestration platform has become established, Gambill said, the company will develop platforms for more expensive carbon removal methodologies such as agroforestry, kelp farming, embedding CO2 in construction materials, and direct air carbon capture technologies.

As for whether carbon markets encourage companies (and, to a lesser extent, individuals) to continue emitting carbon unabated, Gambill pointed out that avoiding the worst impacts of climate change requires removing CO2 from the air. “Our position is that the world needs to ’emit less, and remove the rest,’” Gambill said. “Even if we turned off all sources of emissions tomorrow, we will be dealing with the effects of climate change that we see today for hundreds of years to come.”

Gambill is one of many who believe that the world needs to take an all-of-the-above approach to combating climate change. And Nori has found a way to connect financial resources to vital but often undervalued agricultural practices. If its business model succeeds, we’ll all be better off for it.