If you can’t beat ’em, point out their typos.

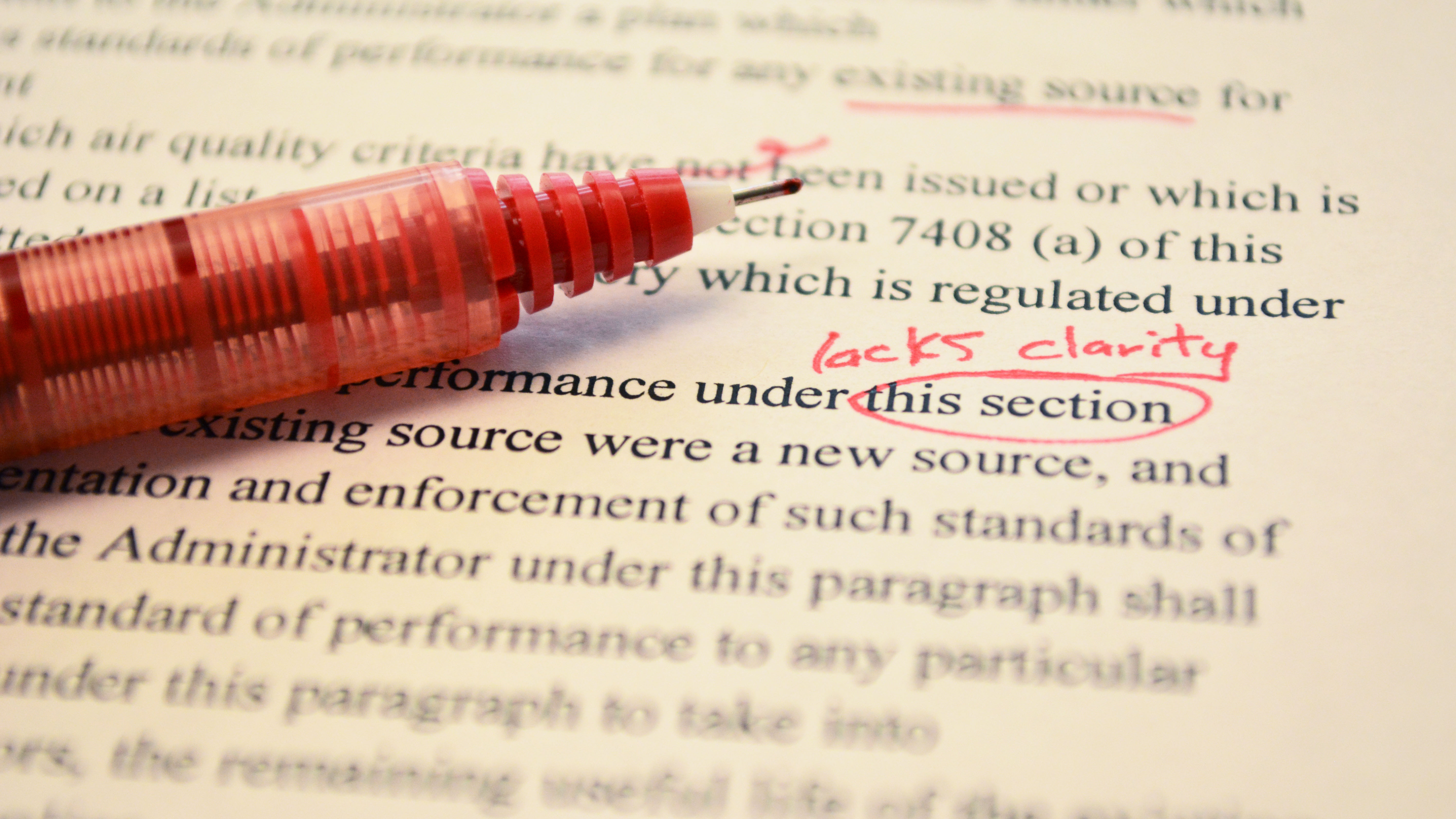

That seems to be the lesson of the D.C. Circuit Court’s recent decision in Halbig v. Sebelius, which could render millions of Americans ineligible for health insurance subsidies on the basis of some sloppy syntax in the Affordable Care Act. After surviving more than 50 repeal votes in the House, a Supreme Court challenge to its constitutionality, and a famously rocky online rollout, health-care reform may end up hobbled by a mere drafting error. And the anti-regulatory crowd wasted no time in launching its next AutoCorrect attack: A new suit asks the D.C. Circuit to nix the president’s biggest climate-change initiative—EPA’s “Clean Power Plan”—due to a 25-year-old mistake in the text of the Clean Air Act.

But don’t panic just yet. As others have pointed out, Halbig is far from a done deal. A different federal appeals court, the Fourth Circuit, upheld the insurance subsidies on the same day the Halbig court invalidated them. If the full D.C. Circuit doesn’t end up reversing its three-judge panel’s initial decision (through a sort of mini-appeal known as en banc review), the Supreme Court will almost certainly step in to resolve the circuit split. In the meantime, no one loses her insurance.

The prospects for EPA’s climate rule aren’t so bleak either. First of all, the 12 state attorneys general who filed suit were a bit too quick on the spell-check trigger. Federal courts generally limit review of agency decisions to “final actions,” and the Clean Power Plan is still in draft form. As a result, the current case will probably be dismissed as premature. That won’t stop the state AGs from re-filing as soon as EPA does publish a final rule, but even then, their victory will hardly be assured. Here’s why.

The “Clean Power Plan” is the administration’s catchy(ish) nickname for a set of restrictions on carbon dioxide emissions from power plants, which generate a full third of the nation’s greenhouse gas pollution. EPA’s authority to regulate these emissions derives from a little-used Clean Air Act provision called Section 111(d). The section has been around since 1970, but when a bipartisan majority of Congress overhauled the Clean Air Act back in 1990, it amended 111(d). Twice. The details are complicated (you can read more about them here), but the upshot is simple: Under the language of an amendment that originated in the Senate, regulating power plants’ carbon emissions is perfectly kosher; under the House’s amendment, not so much.

Competing House and Senate amendments—doesn’t Congress have an app for that? Yep, even back in the digital dark ages of 1990, there was software designed to identify overlapping or incompatible changes to statutory text. But the conference committee charged with reconciling the House and Senate bills didn’t have time to run it. As a result, both 111(d) amendments ended up in the compromise bill that was passed by both chambers and signed by the first President Bush. Meaning that both versions are, in some sense, the law of the land.

A self-contradicting statute—doesn’t the judiciary have an app for that? Sort of. Federal courts certainly have an established rule for dealing with vague or ambiguous laws. Under the Chevron doctrine, if a statute does not “speak clearly” with respect to a particular issue, courts will defer to any reasonable interpretation offered by the executive agency charged with implementing the law. In this case, the EPA maintains that the Senate amendment is more consistent with the Clean Air Act’s overall structure and purpose. If Chevron applies, that justification should pass muster.

The tough question is whether Chevron will apply. It’s hard to see how a court could find that the competing amendments to Section 111(d) “speak clearly.” But are the amendments “ambiguous” in the Chevron sense, or are they something else altogether—say, nonsensical?

Plenty of legal experts have shared their views, but at the end of the day, the opinions that really matter will be those of nine black-robed individuals in Washington, D.C. Handily enough, five of the Big Nine previewed their positions in a recent, fractured decision about an immigration rule. In Scialabba v. Cuellar De Osorio, the Supreme Court was confronted not with two contradictory versions of a single statutory section, but with a single statutory section that contained two seemingly contradictory instructions. (Cut Congress some slack, you guys. Drafting laws is really hard.) Justice Kagan, writing for herself and Justices Ginsburg and Kennedy, called the statute “Janus-faced,” concluded that its “internal tension ma[de] possible alternative reasonable constructions,” and deferred to the Board of Immigration Appeals’ interpretive choice. Chief Justice Roberts, writing for himself and Justice Scalia, disagreed that the two clauses were truly in conflict but, even more importantly, rejected the idea that Chevron was “a license for an agency to repair a statute that does not make sense.” In Roberts’ view, “Direct conflict is not ambiguity, and the resolution of such a conflict is not statutory construction but legislative choice.”

The other four justices didn’t weigh in on this particular question in Scialabba, so it’s not clear whether Kagan’s or Roberts’ camp will carry a majority if and when litigation over the Clean Power Plan reaches the high court. But it’s also not clear that the vote count will matter, because either way EPA should retain authority to regulate carbon emissions from power plants.

Come again? First, consider Justice Kagan’s view. If her logic controls, the court will apply Chevron, defer to EPA’s interpretation of Section 111(d), and affirm the agency’s authority to regulate carbon emissions from power plants. A win for EPA and the president.

Alternatively, assume that Chief Justice Roberts gets the majority. The two amendments to Section 111(d) are almost undoubtedly in “direct conflict,” so, in Roberts’ view, EPA’s interpretation doesn’t warrant deference. Now what? Roberts’ Scialabba opinion doesn’t say what the court should substitute for Chevron in the case of a provision that’s truly at war with itself. But if the chief justice believes that giving effect to only one of the two amendments represents a “legislative choice,” the judicial branch has no more business picking a winner than EPA. (In fact, courts are even less suited than executive agencies to this sort of policy decision. Agencies are, at least, indirectly accountable to the people, because agency leaders serve at the pleasure of a democratically elected president.) If it’s not possible to honor the House and Senate amendments simultaneously, the only remaining option is to throw out both as invalid, in which case Section 111(d) would revert to its pre-1990 form.

That’s the reason backers of the climate rule shouldn’t panic: Under the earlier version of Section 111(d), EPA would still have authority to regulate carbon emissions from power plants. The agency still wins.

Oh, and if the current Congress doesn’t like that result? Well, it remains free to share its preferred method for addressing climate change at any time. There’s an app for that, too. It’s called new legislation.