Until a year ago, Kate Levin was feeling pretty calm. Her friends back in her home state, Pennsylvania, kept talking about this thing called fracking. It was, they said, not great. But Levin lived far away, in Michigan. “I tried not to pay attention to it,” says Levin.

There wasn’t an obvious tipping point between paying attention and not paying attention — just a gradual and eventually overwhelming sense that not paying attention was, in Levin’s words, stupid. “I am going to find out about this,” she told herself. “I am going to find out if this is happening locally.”

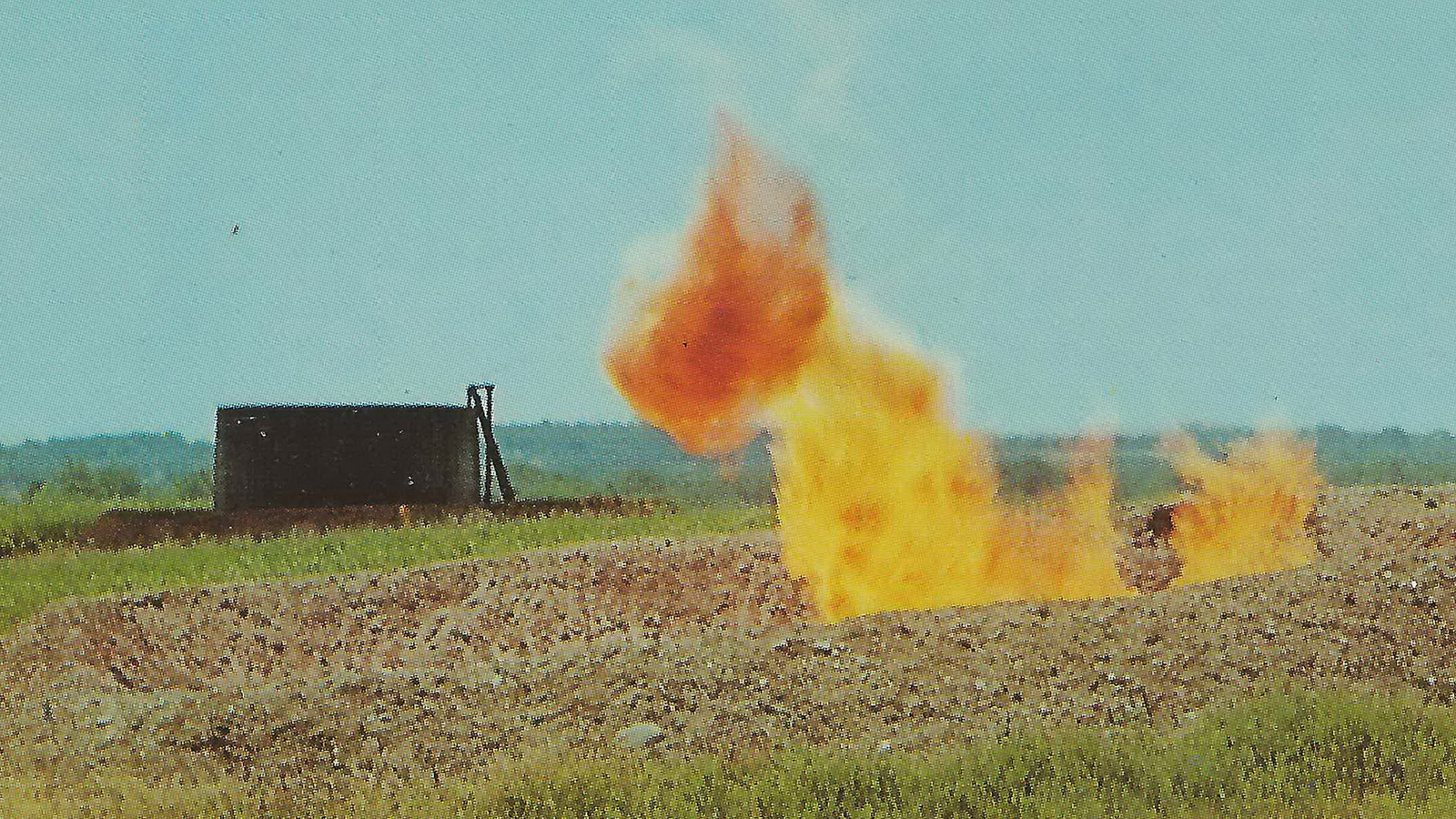

It was. Michigan was a fairly typical state in that people had been drilling it for oil and gas since the 1880s. But the pickings were slim. it wasn’t that there wasn’t anything there; natural gas in particular was all over the Collingwood/Utica and Antrim shale formations. But it was at least 10,000 feet underground, which meant that getting it out was more expensive than taking it out of, say, an easy peasy rock formation like Pennsylvania’s Marcellus shale, which maxes out at 9,000 feet deep.

Expensive or not, though, claims were being staked. In 2010, Michigan’s Department of Natural Resources auctioned off oil and gas leases for 118,000 acres of state land for a record $178 million. The previous record had been $23.6 million, back in the ’80s. Fracking wells began to appear in residential neighborhoods. Two big energy players in the state, Encana and Chesapeake Energy, were found guilty of colluding with one another so that they could underbid on lease prices.

Levin began to look around for environmental groups in Michigan that were responding to fracking. She didn’t find much. Prices for natural gas were still so low that Michigan wasn’t exactly becoming a boomtown. Environmental groups in the area weren’t sure how to approach the issue.

There was time to tighten up environmental regulations around the state, but how would that be done? Because of the Energy Policy Act of 2005, fracking was exempt from regulation under the Safe Drinking Water Act. Michigan’s own environmental regulations around oil and gas drilling dated back to the 1930s, and appeared to endorse extracting as much of it as possible:

It is accordingly the declared policy of the state to protect the interests of its citizens and landowners from unwarranted waste of gas and oil and to foster the development of the industry along the most favorable conditions and with a view to the ultimate recovery of the maximum production of these natural products.

Levin was not interested in the ultimate recovery of the maximum production of these natural products. She was interested in water — the state is home to over 20 percent of the world’s aboveground freshwater supply, and the Collingwood/Utica Shale lies under the headwaters of the Manistee and Au Sable rivers.

She met up with several groups and ultimately settled on one called The Committee to Ban Fracking in Michigan, a political campaign group with several hundred volunteers whose views are pretty much summed up by their name.

Banning fracking is a tricky issue in Michigan. While several cities have passed resolutions supporting a ban, none of them appear to have actually banned it. Some argue that state law supersedes any effort to ban it at the township level, the way that New York has managed to do very successfully. Others argue that it could totally happen, and that precedent has been misread. In any case, it hasn’t been tested in court yet.

Instead, the group is focused on another political tool — the ballot initiative. A ballot measure could be used not only to change the language of the state’s oil and gas regulations, but to make it extremely difficult to modify further.

Ballot initiatives date back to the Progressive Era a century ago and play a complex role in modern politics. Intended as a tool to help regular citizens override the cronyism and compromises of state government, they’ve come to be used — like most political tools — by a variety of people for a variety of purposes. In Michigan, in particular, they’ve been very popular with anti-abortion groups.

Getting an initiative on the ballot isn’t easy. The Committee to Ban Fracking in Michigan will have to find 258,088 people across the state, get them to fill out forms, collect those forms, verify that the people who filled out those forms are real humans, and turn them in to the state. The last time they tried it, they set up tables at events like farmer’s markets and the Mackinac Bridge Walk. They got about 30,000 the first time, and 70,000 the next. They’re trying again in 2015.

Trying to gather 258,088 signatures is a “huge process,” says LuAnne Kozma, who co-founded a related organization, Ban Michigan Fracking. But it’s still less daunting than going from town to town helping to pass local legislation, which is what New York and Pennsylvania had to do. If those states had access to ballot initiatives, they might have done things differently. You use the tools you have.

And the process has other benefits. Michigan is a state of cars and suburbs. There aren’t many opportunities to mingle and share ideas with other people in a public space. So trying to get something on the ballot is like entering the Olympics of sociability. As a folklorist, Kozma has the advantage of having traveled all over Michigan in search of local history. “I know every part of the state,” she says. “I know how to pronounce all the county names. And the great thing is — you’re out there, talking to people.”

For Levin, it has also meant a lot of interesting moments — like going on a jaunt with her husband to stake out a local dump that is taking deliveries of radioactive fracking waste from out of state. It looked surprisingly nice, she said. Landscaped, even, with a nice grassy hill. Though the hill, she adds, was probably landfill.

Even if Michigan never has its fracking boom, there’s still work to be done making sure fracking’s effects don’t reach the state in other ways. A few Michiganders are big fans of fracking, says Levin. They’ll tell you right away. But most people in the state aren’t even aware of it yet. When they learn about it though, she says, they get the risks immediately. “We have so much water here. That’s our pride.”