This story was originally published by Mother Jones and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

As the United Nations convenes in New York this week for its 70th General Assembly, one of the most prominent items on the schedule is to formally sign off on its brand-new Sustainable Development Goals. The SDGs, which have been in the works for a few years, are basically a to-do list for all the world’s governments from now until 2030. They’re also a seemingly impenetrable pile of diplo-jargon.

“If you were to pick up the document, your first reaction could be that it’s a lot of ‘blah blah blah,'” said Peter Hazlewood, director of development at the World Resources Institute.

Still, the SDGs could have a significant impact on the allocation of resources to fight climate change and other environmental issues over the next decade. Here’s what you need to know.

Replacing the Millennium Development Goals. The SDGs are a follow up to the Millennium Development Goals, enacted in 2000. There were eight specific MDGs, all targeted at different aspects of extreme poverty: Reduce the child mortality rate by two-thirds, vastly expand access to clean drinking water, turn the tide against HIV/AIDS, etc. Of course, the goals aren’t legally binding. Instead, the point was to give developed-country governments and international financial institutions such as the World Bank a target to shoot at when they make decisions about how to spend aid dollars or invest in certain projects. It’s a way of saying: “We agree that these are the world’s top priorities right now.”

The “we” in that sentence was pretty controversial, since — according to lore, at least — the goals were drawn up behind closed doors in the U.N. basement by a group of elite diplomats. For that reason, it took years for a critical mass of governments to actually rally behind the MDGs and start to implement them. And even then, the they were sometimes criticized for being too narrow and not sufficiently focused on the root causes of poverty.

As of the end of this year, the MDGs will have reached their expiration date. How well did we do on meeting them? So-so. Global poverty and childhood mortality have been greatly reduced; for example, between 1990 and 2015 the portion of people in developing countries living on less than $1.25 per day fell from 50 percent to 14 percent. Still, obviously, global poverty has not been eradicated. The U.N.’s own recent assessment found many goals were un-met, especially with respect to gender equality and conflict refugee issues.

And even in the best scenario, it’s far from clear how much impact the MDGs actually had on any of the issues they sought to address. During the same time period, for example, China was developing rapidly and opening up to international trade, which had a huge impact on lifting its citizens out of poverty — quite separately from anything the U.N. was doing. But it’s safe to say that the MDGs loomed over budget conversations at agencies like USAID, and in that way had a tangible impact on how the U.S. and other rich governments spent money on aid.

The MDGs “were far from perfect, and you cannot attribute all progress to them,” Hazlewood said. “But you can make a strong case that they had a galvanizing effect.”

So what are the Sustainable Development Goals? This time around, while still including poverty, the focus has swung much more toward environmental issues, including climate change adaptation. Here are the 17 goals:

- End poverty in all its forms everywhere

- End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition, and promote sustainable agriculture

- Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages

- Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all

- Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls

- Ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all

- Ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable, and modern energy for all

- Promote sustained, inclusive, and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all

- Build resilient infrastructure, promote inclusive and sustainable industrialization, and foster innovation

- Reduce inequality within and among countries

- Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable

- Ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns

- Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts

- Conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas, and marine resources for sustainable development

- Protect, restore, and promote sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems, sustainably manage forests, combat desertification, halt and reverse land degradation, and halt biodiversity loss

- Promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all, and build effective, accountable, and inclusive institutions at all levels

- Strengthen the means of implementation and revitalize the global partnership for sustainable development

If that seems like a lot, well, it is. While the MDGs were too narrow, the SDGs could very well be too broad. As Michael Specter pointed out in the New Yorker, “goals such as ‘End poverty in all its forms everywhere,’ may seem so broad that they will be easy to ignore.” U.K. Prime Minister David Cameron said as much last year, warning that with so many goals, “there’s a real danger they will end up sitting on a bookshelf, gathering dust.” Even just reading the list seems overwhelming; imagine being a head of state trying to implement it in your sprawling national bureaucracy.

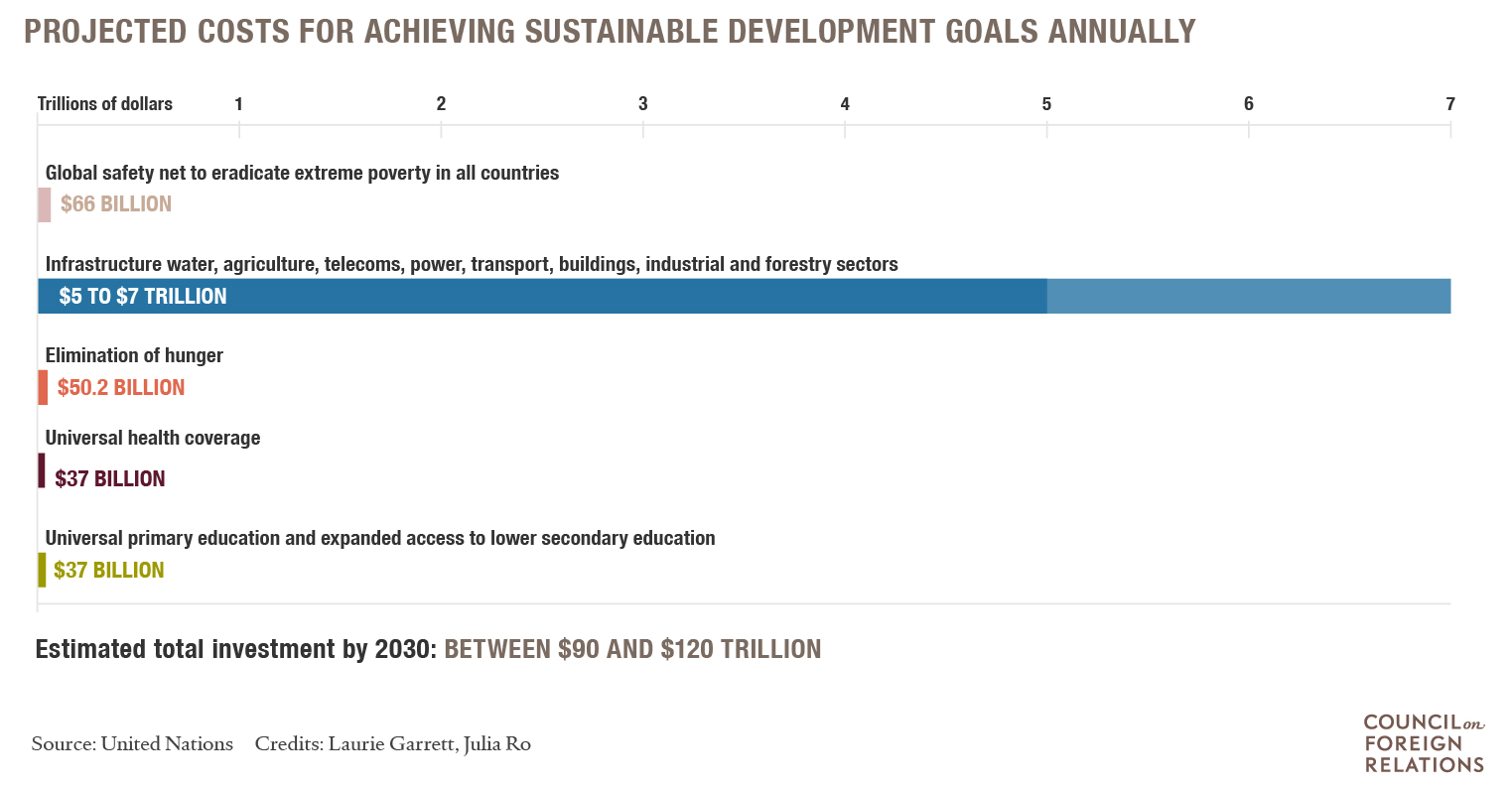

And they’re not cheap: By some estimates, they could cost more than $7 trillion a year to implement, and there’s still no clear consensus on where exactly that money will come from. It would likely be a mix of private-sector investment; aid from the U.N. and developed countries; and increased spending by developing countries.

Council on Foreign Relations

At the same time, the goals’ breadth could be a strength, as less affluent countries become more involved in implementing them — as opposed to only being on the receiving end of aid dollars. They could provide an impetus for developing countries to get more serious about things under their control, like empowering women, or conserving natural resources, or making urban planning decisions with an eye toward climate impacts. At the very least, the goals provide ammunition for diplomatic peer-pressure: No country wants to look lackadaisical compared to the one next door, or act in direct contravention of the goals, lest they scare off donors or investors. And it could be a way for U.S. agencies to justify increased spending on climate adaptation.

“These are universal goals,” Hazlewood said. “It’s not just about what the U.S. should be doing with countries in Africa; it’s about what every country in the world needs to do.”

What’s next? Of course, the U.N. can’t compel any country to do any of these things. So the goals won’t matter unless individual national governments take them seriously. Unlike the old MDGs, the SDGs were developed over several years with maximum transparency, involving a huge, diverse cast of governments, NGOs, and private companies. The rationale for that strategy was to increase everyone’s stake in the goals, so that when they come into effect, countries will swiftly incorporate them into national policy decisions — in other words, take them off the page and into practice. We’ll have to wait and see if that will really happen.

“With the MDGs it took years to get any kind of traction and for countries to take them seriously,” Hazlewood said. “But this time we can get the process off to a better start.”