You can do a lot in 100 days. Fitness programs promise that you can go from couch potato to distance runner. Intrepid journalist Nellie Bly traveled around the world with four weeks to spare, more than a decade before the first airplane flight. President Franklin D. Roosevelt saved the United States banking system and implemented most of his New Deal programs during his first three months in the White House. But is 100 days enough time to put the world on a path to a long-term deal on climate change?

We’re about to find out. After this week’s negotiating sessions in Bonn, Germany, there will be 87 days to go until the Paris conference on climate change this December, and details are slowly emerging on what that final agreement may look like and what actions individual countries will take going forward.

To date, 56 countries have submitted their emission-reduction pledges, or intended nationally determined contributions (INDCs) in United Nations parlance. While these INDCs cover more than 60 percent of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, they only account for about one-quarter of the 196 countries that are members of U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). The list of countries that have not yet submitted their pledges includes a number of key emitters, including the fourth, seventh, and eighth largest emitters in absolute terms — India, Brazil, and Indonesia, respectively.

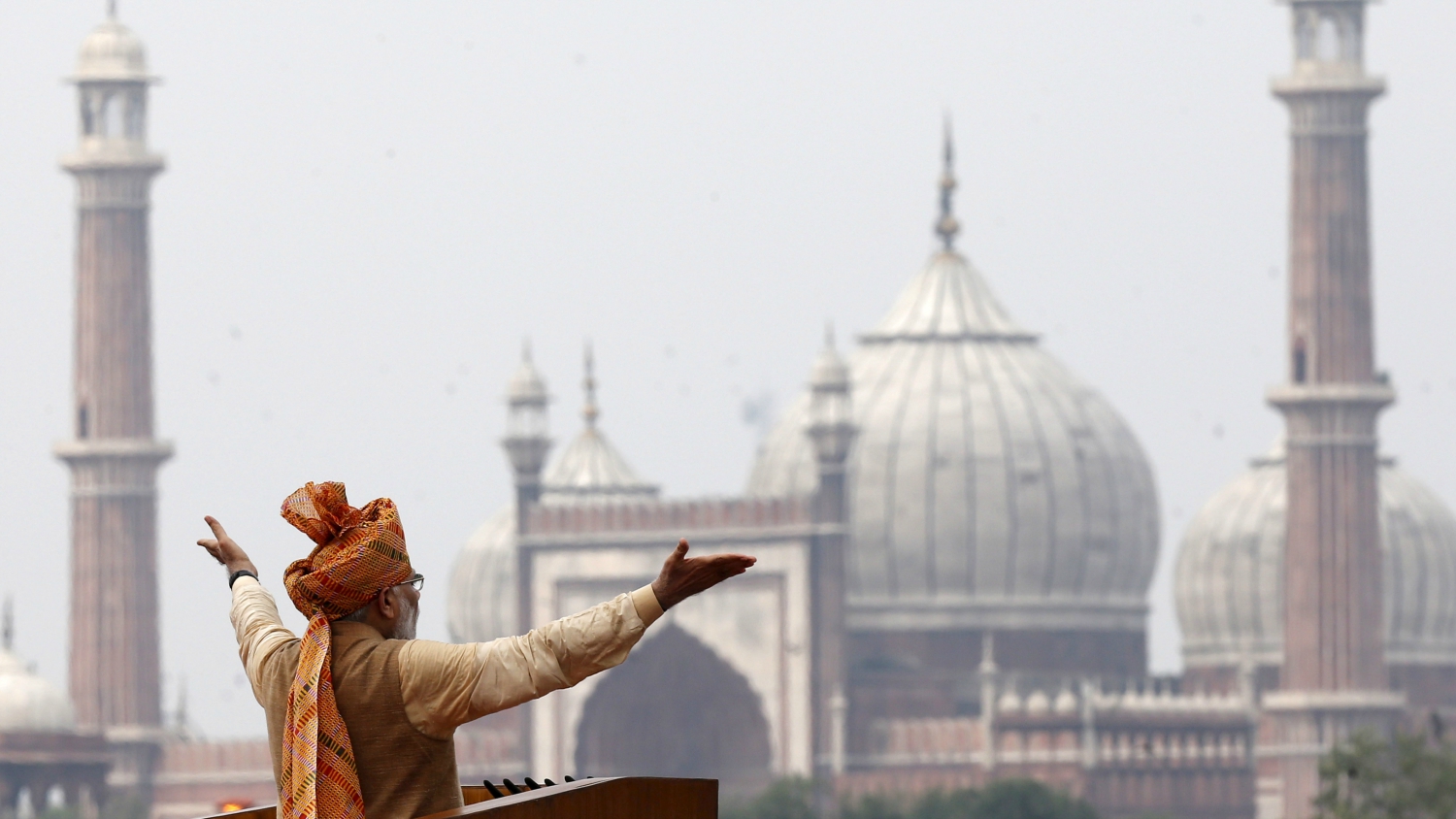

We do not yet know what India’s INDC will look like, though information continues to leak out, bit by bit. Last week, Environment Minister Prakash Javadekar indicated that the government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi will stick to its long-term approach; that is, the country will not commit to a year when its GHG emissions will peak. Instead, India will commit to a variety of other initiatives taking on both mitigation and adaptation, and the country may follow Mexico’s lead by pledging to ramp up its actions if it receives enough financing from developed countries. Based on early reports, these will likely include pledges to reduce the carbon intensity of its economy by 20 to 30 percent and to dramatically ramp up solar power production. This strategy rejects suggestions from Modi’s chief economic adviser, Arvind Subramanian, who had encouraged the prime minister to abandon a focus on foreign financing and adaptation in favor of committing to more aggressive emissions reductions.

Either way, we will know India’s approach soon enough, as it will likely submit its INDC later this month, perhaps timed to the United Nations General Assembly, which opens on Sept. 15.

Regardless of its contents, India’s submission is likely to disappoint many observers. According to a recent analysis, pledges thus far will put us on course to emit between 56.9 billion and 59.1 billion tonnes of GHGs a year by 2030, 58 to 64 percent higher than the cap scientists have identified to keep global temperatures from rising more than 2C above pre-industrial levels. If the rumors are true, India’s proposed program would do little to change this trajectory. These factors may lead some to conclude that the Paris agreement will be a failure, as it will not guarantee that emissions stay within this safe range.

Yet, perhaps the most important component of whatever agreement comes out of Paris is the one receiving the least amount of attention — what comes next. Because the Paris conference will not be the last word on global efforts to fight climate change; in a way, it will be only the first. Buried in the 83-page “streamlined” version of the negotiating text is a lengthy section dealing with so-called monitoring, reporting, and verification (MRV). This issue is what will ultimately determine the success or failure of the Paris conference, as it will define the process by which countries keep tabs on each other’s commitments, punish laggards, reward parties that fulfill their pledges, and commit to additional reductions beyond 2030.

Given the significance of MRV, the negotiating text leaves much to be desired. It includes five different options for the timeframe of commitments alone, including “a period to be determined by the governing body,” which does not exactly instill confidence in the process. As this could become the issue on which the entire climate regime that will come out of Paris hinges, it is incredibly important that developed and developing countries work diligently to reach agreement on a strong MRV system. And this is where India comes into the picture.

Before they submit their INDC, Indian officials have indicated that they plan to host a summit of “Like-Minded Developing Countries,” such as Brazil and Indonesia, to develop a consensus on a variety of important topics. This occasion would be a perfect opportunity for India to lead the way among developing nations who do not yet feel ready to make the same kind of commitment the Chinese did. If emission cuts or a peak year are bridges too far for this year’s Paris agreement, then India should be a consistent, public champion of participation in strict MRV measures, even if India’s most robust action is still in the future. India and its like-minded allies could come out in favor of a unified MRV process that includes a consistent timeline for review and a firm pledge to issue new, more ambitious carbon reduction actions at each review session.

Such an announcement need not be formally included in the INDCs of the states in question, at least not right away. There could be a separate statement of intent, made public before the UNFCCC negotiations at Paris begin. Ideally, the countries taking part in the summit later this month could issue a joint declaration endorsing a proposal floated by the Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS). The plan outlines a comprehensive MRV strategy that calls for UNFCCC parties to ratchet up their mitigation, adaptation, and financing pledges at five-year intervals. The plan, according to reporting from Bonn, is receiving support from many negotiating parties. A strong, public endorsement by India and a group of like-minded developing countries would help maintain momentum behind the idea through the Paris negotiations.

This approach represents the best path forward from Paris, the one that is most likely to give us a fighting chance to stay below 2C. It also retains one of the central tenets of the UNFCCC — the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities — which calls for all countries to take action on climate change, but to differing degrees. India and its developing country partners could then calibrate their ambition to their specific economic circumstances, the prevailing market conditions for the proliferation of renewable energy sources and battery technology, and the ebb and flow of multilateral assistance.

Ultimately, we believe that such a declaration on the part of India and its fellow Like-Minded Developing Countries would send an important signal to the other parties heading into Paris. It would show that they plan to participate in the process in good faith in order to achieve an agreement that can help the world stave off the worst impacts of a changing climate. With less than 100 days left to Paris, there is little time to spare. Countries must take steps now to speed the process along and increase the odds that we will get not just any agreement, but the right agreement. It is time for India and other emerging economies to do their part.

—–

Tim Kovach is an independent analyst and blogger from Cleveland who researches and writes about climate change, disaster risk reduction, and environmental peacebuilding at timkovach.com. Neil Bhatiya is a policy associate at The Century Foundation, a progressive nonpartisan think tank, where he studies U.S. climate policy.