A bold demand has recently become standard among many U.S. environmentalists and progressives: ban fracking. Major green groups such as the Sierra Club have called for ending the practice. Bernie Sanders gave the issue more visibility when he first endorsed a national fracking ban four months ago. Then, earlier this summer, his camp pushed (unsuccessfully) for a ban to be incorporated into the Democratic Party’s platform.

But is a full-scale fracking ban a good idea? Some pro-environment policy experts and activists don’t think so.

Democratic politicians are divided. Hillary Clinton has resisted a full ban on fracking. But she has embraced regulating the emissions of methane and other potential air and water contaminants from the process, along with allowing local bans. “By the time we get through all of my conditions, I do not think there will be many places in America where fracking will continue to take place,” Clinton said in a March debate. In 2012, Vermont Gov. Peter Shumlin made his state the first to ban fracking, and New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo followed suit in 2014. But some governors of oil- and gas-rich states, such as Colorado’s John Hickenlooper, enthusiastically promote the practice. Even California Gov. Jerry Brown, a noted climate hawk, has rejected calls to ban fracking. Leading climate activist (and Grist board member) Bill McKibben called this Brown’s “environmental blind spot” in the Los Angeles Times.

So who’s right? Let’s examine the arguments on both sides.

The case for banning fracking

There are two main arguments for banning fracking: to eliminate pollution in local communities and to reduce climate change. The local effects have been the driving force for many grassroots environmental activists.

“The ban on fracking would certainly impact the future energy mix, but that’s not the reason that people are calling for a ban on fracking,” says Jesse Coleman, a researcher at Greenpeace. “People are calling for a ban on fracking because it affects today’s health of people living near fracking wells. There are fracking chemicals in people’s blood in Wyoming and there are pollutants in people’s lungs from fracking wells in Colorado.”

Green leaders are following the bottom-up energy of “fracktivists” from affected communities. “What’s unique about fracking is the movement is truly a grassroots movement,” says Erich Pica, president of Friends of the Earth. “In New York, Pennsylvania, Colorado, and California, this bubbled up from the grassroots stating what they wanted in very clear terms: we don’t want this anymore.”

“Of course fracking should be banned,” says Iris Marie Bloom, director of Philadelphia-based Protect Our Waters, one of those grassroots anti-fracking groups. “There is absolutely no way to handle the waste.” Groups like hers are particularly concerned about polluted wastewater that’s generated during the fracking process, which is often injected back underground, where it could contaminate water supplies or trigger earthquakes. Bloom also notes that when a shale formation is broken by fracking, it can release uranium or arsenic into nearby water supplies.

Cutting back on fracking would also help prevent catastrophic climate change, these activists argue. Fracking has allowed oil and gas companies to get ahold of reserves that were previously impossible, or too expensive, to extract. By boosting supplies of oil and gas, the fracking boom has cut their prices dramatically. Ending fracking would increase oil and gas prices. That could be a good thing for the climate because it would give a market advantage to wind and solar for electricity production and push society to rely less on gasoline for transportation.

The case against

Some environmentalists and analysts, on the other hand, argue that banning fracking would not help the fight against climate change. Fracking has unleashed huge supplies of natural gas in the U.S., and they contend that natural gas can play an important role in curbing greenhouse gas emissions by displacing coal.

When it’s burned, natural gas releases only half as much carbon pollution as coal. The natural gas boom has been a major cause of the shuttering of coal plants in the U.S. in recent years, which has contributed to a decrease in the nation’s greenhouse gas emissions, according to the EPA.

But are those climate gains illusory? Recent independent studies have found that lots of natural gas leaks out of drilling and transmission infrastructure before it ever makes it to power plants or homes to be burned. Unburned natural gas is mostly methane, a highly potent greenhouse gas when it escapes into the atmosphere. The EPA’s estimates don’t account for this leakage, but many researchers believe the leaks may moot natural gas’s perceived climate advantage over coal. This helps to explain why the Sierra Club, which used to support natural gas, changed its position and now calls for moving away from gas as quickly as possible.

Some analysts, though, like Michael Levi at the Council on Foreign Relations, argue that limiting methane leakage through regulation is the solution, not ending fracking or spurning natural gas altogether. In 2050, when our emissions need to be 80 percent lower than 1990 levels, we won’t want to be using natural gas. In 2025, however, more gas would be a positive step, he says, helping us continue to shift the electricity sector away from coal. This is what politicians like Clinton mean when they call gas a “bridge” to a clean energy future.

Natural gas advocates also contend that wind and solar can’t be ramped up fast enough to fully replace coal in the next few years. Coal and gas each currently account for 33 percent of U.S. electricity generation, compared to 5.3 percent for solar and wind combined. To build the solar and wind capacity to replace coal will take a long time, say these pro-gas environmentalists, and right now there aren’t great options for storing wind or solar power, making them potentially problematic sources for providing power 24/7 and at peak demand times.

“We cannot make a lot of progress with rapid decarbonization in the next 20 years,” says Alex Trembath, communications director at the Breakthrough Institute, a think tank founded by the heterodox environmentalists Ted Nordhaus and Michael Shellenberger. “While we improve clean energy technologies with innovation and deployment, natural gas has proved to be the biggest emissions reducer in the power sector in the last decade and can continue to replace coal while we try to make renewables cheaper. By 2040, you’ll be able to replace natural gas capacity being built now with renewables.”

The Environmental Defense Fund, a more mainstream green group, also argues that gas and oil will be with us for decades and so the focus should be on better regulating all methods of extraction rather than banning only fracking.

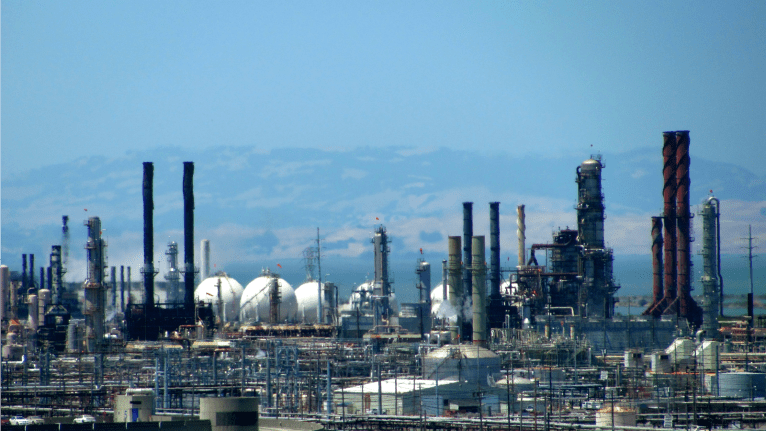

“You could wave a magic wand and ban all fracking tomorrow and many of the environmental challenges associated with oil and gas development would remain,” says Mark Brownstein, vice president in the climate and energy program at EDF. “I think it’s hard to make an argument that hydraulic fracturing is by itself the worst and dirtiest way to produce oil when there are so many bad and dirty ways to produce oil.”

Brownstein continues, “A case in point is methane: We’ve been studying the methane issue, with leading academic institutions, for the last two and a half years. What we’ve learned is the majority of methane emissions are coming from the transportation and distribution system [for natural gas] in the U.S. Only 30 percent is coming from production and only a subset of that is coming from fracking.”

And, Brownstein says, since most regulation of oil and gas drilling happens at the state level, where it’s easier to get things done, there are opportunities for real progress. For example, EDF worked with activists and industry in Colorado to enact new rules in 2014 to curb methane emissions and other pollution from oil and gas operations. The state government wasn’t open to a fracking ban, but the regulations got relatively widespread support.

Still, regulations are only effective if they’re followed, and too often they aren’t. The Deepwater Horizon oil rig explosion, for example, was caused by BP and Halliburton violating existing federal safety rules. Whether allowing fracking to proceed could be helpful to reducing emissions in a laboratory is a different question than whether it would work in the real world.

The counter-counterargument

Anti-fracking activists also point out that the more we build up the natural gas industry now, the harder it will be to get rid of later. As gas pipelines and power plants come online, gas companies become more powerful and a political economy is built up around them. “Once permanent infrastructure for the natural gas industry is erected, it’s going to be just like the coal industry and oil industry,” says Pica. “We’re going to be fighting the titans of natural gas 10, 15 years from now.” To get a preview of how that will go, just look at the current fight over coal: Every EPA rule that might reduce coal dependence gets congressional Republicans voting to block it and state attorneys general and industry groups suing to stop it.

Also, renewables could be much more affordable, viable, and widespread by 2025 than pro-gas analysts expect. Prices for solar and wind power have plummeted far more than was predicted 10 years ago, and they could keep outpacing projections. There could be technological breakthroughs on energy storage or unforeseen economic changes. And if President Obama’s Clean Power Plan survives a court challenge and a presidential election, then federal regulations will be pushing renewables forward as well.

If not a ban now, at least some strong rules

In the current political climate, though, a national fracking ban is as unlikely as single-payer health insurance. So some activists are focusing on repealing the “Halliburton loophole,” a provision in the 2005 energy law that exempted fracking operations from the Safe Drinking Water Act. This would be an uphill climb too, but at least Clinton recently endorsed this position.

The green groups pushing to close the loophole are seeing it as a first step toward ending fracking. They hope to raise public awareness about air and water pollution from fracking operations, creating the political momentum for state and local fracking bans, and they want to create a set of federal regulations that would make fracking more difficult or uneconomical.

“[Repealing] the Halliburton loophole is a means to an end,” says Pica. “It is more of a public disclosure piece: then you’ll be able to create public pressure and regulatory pressure to ban certain chemicals and certain types of practices.”

It’s also important to remember that the demand to ban fracking, while it might be unrealistic in the next Congress, is part of a larger aspirational agenda that calls for a wartime mobilization to combat climate change. Like calling for a carbon tax, it’s a statement of what should be done in the hopes of dragging the political system along. Absent massive government intervention, we’re going to continue burning oil and gas and it will have to come from somewhere. But massive government intervention is what we need if we’re going to dramatically slash carbon emissions. Fracking is only a necessary evil if we choose for it to be so.