Humans are “eating away at our own life support systems” at a rate unseen in the past 10,000 years by degrading land and freshwater systems, emitting greenhouse gases, and releasing vast amounts of agricultural chemicals into the environment, new research has found.

Two major new studies by an international team of researchers have pinpointed the key factors that ensure a livable planet for humans, with stark results.

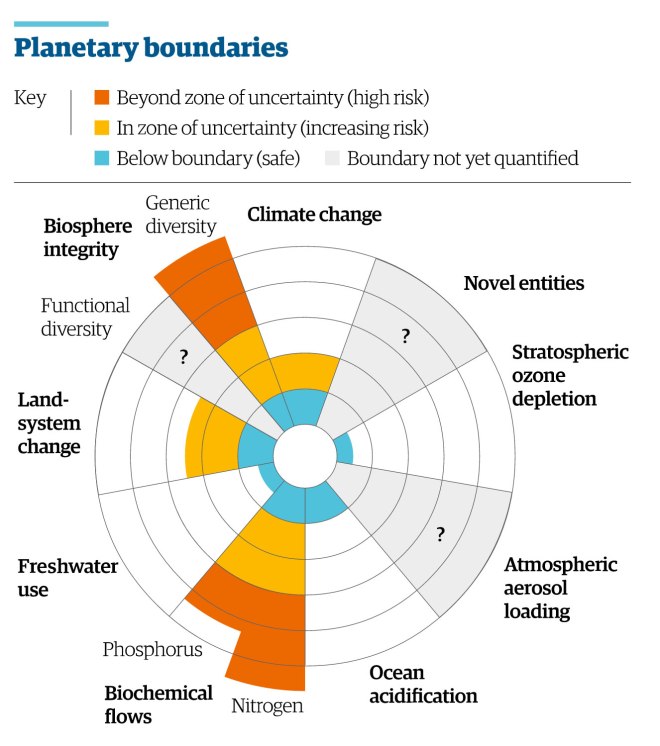

Of nine worldwide processes that underpin life on Earth, four have exceeded “safe” levels — human-driven climate change, loss of biosphere integrity, land system change, and the high level of phosphorus and nitrogen flowing into the oceans due to fertilizer use.

Researchers spent five years identifying these core components of a planet suitable for human life, using the long-term average state of each measure to provide a baseline for the analysis.

They found that the changes of the last 60 years are unprecedented in the previous 10,000 years, a period in which the world has had a relatively stable climate and human civilization has advanced significantly.

Carbon dioxide levels, at 395.5 parts per million, are at historic highs, while loss of biosphere integrity is resulting in species becoming extinct at a rate more than 100 times faster than the previous norm.

Since 1950, urban populations have increased sevenfold, primary energy use has soared by a factor of five, while the amount of fertilizer used is now eight times higher. The amount of nitrogen entering the oceans has quadrupled.

All of these changes are shifting Earth into a “new state” that is becoming less hospitable to human life, researchers said.

“These indicators have shot up since 1950 and there are no signs they are slowing down,” said professor Will Steffen of the Australian National University and the Stockholm Resilience Center. Steffen is the lead author on both of the studies.

“When economic systems went into overdrive, there was a massive increase in resource use and pollution. It used to be confined to local and regional areas but we’re now seeing this occurring on a global scale. These changes are down to human activity, not natural variability.”

Steffen said direct human influence upon the land was contributing to a loss in pollination and a disruption in the provision of nutrients and fresh water.

“We are clearing land, we are degrading land, we introduce feral animals and take the top predators out, we change the marine ecosystem by overfishing — it’s a death by a thousand cuts,” he said. “That direct impact upon the land is the most important factor right now, even more than climate change.”

There are large variations in conditions around the world, according to the research. For example, land clearing is now concentrated in tropical areas, such as Indonesia and the Amazon, with the practice reversed in parts of Europe. But the overall picture is one of deterioration at a rapid rate.

“It’s fairly safe to say that we haven’t seen conditions in the past similar to ones we see today and there is strong evidence that there [are] tipping points we don’t want to cross,” Steffen said.

“If the Earth is going to move to a warmer state, 5-6 degrees C warmer, with no ice caps, it will do so and that won’t be good for large mammals like us. People say the world is robust and that’s true, there will be life on Earth, but the Earth won’t be robust for us.

“Some people say we can adapt due to technology, but that’s a belief system, it’s not based on fact. There is no convincing evidence that a large mammal, with a core body temperature of 37 degrees C, will be able to evolve that quickly. Insects can, but humans can’t and that’s a problem.”

Steffen said the research showed the economic system was “fundamentally flawed” as it ignored critically important life support systems.

“It’s clear the economic system is driving us towards an unsustainable future and people of my daughter’s generation will find it increasingly hard to survive,” he said. “History has shown that civilizations have risen, stuck to their core values and then collapsed because they didn’t change. That’s where we are today.”

The two studies, published in Science and Anthropocene Review, featured the work of scientists from countries including the U.S., Sweden, Germany, and India. The findings will be presented in seven seminars at the World Economic Forum in Davos, which takes place between Jan. 21 and 25.

This story was produced by The Guardian as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

This story was produced by The Guardian as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.