The world was hoping for something grand from President Obama at Tuesday’s U.N. Climate Summit. He offered grand words. But because his hands are tied by a recalcitrant Congress, he couldn’t offer grand action. So he offered modest action instead.

On Tuesday, to coincide with the summit, the Obama administration announced an executive order pertaining to climate change. Obama promoted it in his lofty speech in the U.N.’s General Assembly Hall, saying, “I’m directing our federal agencies to begin factoring climate resilience into our international development programs and investments.”

But what does that mean? According to experts, it is a good step for the administration to take, but not a huge one, and how much it will accomplish remains to be seen.

It’s important to distinguish between “climate resilience” (a.k.a. climate adaptation) and climate mitigation. They sound like the same technical jargon, but their different meanings matter. Climate resilience, which the executive order addresses, means preparation for changes we expect to result from global warming, like heat waves, droughts, and rising oceans.

Imagine a U.S.-backed loan to help build an irrigation system in Africa. Factoring in climate resilience means asking whether there will be enough water for that system to operate in a few decades when water is more scarce because of climate change. To achieve the highest level of climate resilience, you also would ask how the water requirements of the irrigation project will affect the surrounding community’s water supply in a drier, warmer future. It’s sound policy to take climate change into account when investing in international development programs, but it doesn’t by itself necessarily do anything to limit climate change.

The executive order is almost entirely concerned with resilience. Climate mitigation, which refers to actually reducing the amount the Earth warms by reducing our greenhouse gas emissions, only gets one paragraph in the order’s seven pages. And that is just a vague plan to convene an interagency panel to come up with recommendations for mitigation. “It’s a typical working group that governments set up, so it’s hard to anticipate how promising it will be,” says Steve Herz, senior attorney for the Sierra Club’s international climate program. “It’s consistent with the president’s approach to date, which is, ‘I ain’t getting nothing out of Congress, so I’m going to see what I can do on my own.’ So he’s going to pull the agencies together and see what he can get out of them.”

As for the climate-resilience component of the order, there may be even less to it than meets the eye. As Oxfam America pointed out in a statement, “USAID has already been factoring climate change into its investments since 2012.”

This doesn’t mean there is nothing to Obama’s announcement at all, though. It will, at minimum, expand USAID’s practices to other U.S. development programs. That includes, for example, the Overseas Private Investment Corporation, which provides $3.9 billion in financing and insurance commitments annually.*

It could have some other benefits as well. U.S. representatives with clout at international development agencies will likely follow the administration’s lead. “It will send a message and affect how the World Bank and others invest,” says Jake Schmidt, director of international programs at the Natural Resources Defense Council.

And even just accounting for climate resilience could have some mitigation effects. “It’s unfortunate it didn’t include emissions, but agencies will have to take into account the climate impacts of their investments if they do [climate resilience] right,” says Schmidt. Consider the imaginary irrigation project: If it scores more highly on climate resilience because it uses water and energy more efficiently, that also means it will have lower emissions than, say, an irrigation project that relies on a diesel generator to pump water. The most resilient projects in a natural resource–constrained future will also tend to be the ones with the lowest environmental impact.

So environmentalists are unanimous in praising the executive order. But they are also underwhelmed, and are calling for more action on funding climate mitigation and adaptation efforts in the developing world. “[W]ithout additional financial commitments ultimately these actions will be a drop in the bucket when it comes to the United States’ responsibility to deliver on its obligations under the Copenhagen Accord,” said Oxfam America’s statement.

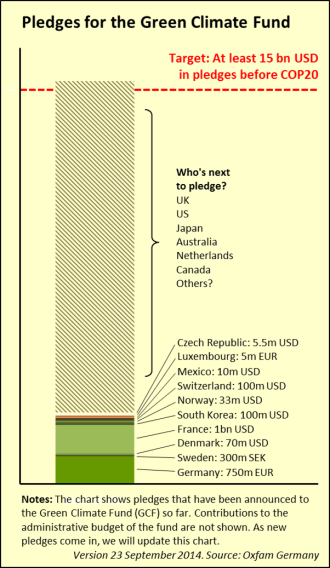

One way to do more would be by committing money to the U.N.’s Green Climate Fund, which is intended to help developing countries cope in a climate-changed world. France and Germany have each pledged $1 billion, and smaller pledges have come from South Korea, Mexico, Denmark, and Norway, among others. By using methods like loan guarantees to attract private investment, the Climate Fund could leverage each dollar for seven times that much spending, according to Bank of America. Peter Ogden and Gwynne Taraska of the Center for American Progress called on Obama Wednesday in The Huffington Post to pony up some American dough. They write:

We at last see a pathway for the fund to meet its goal of a $10 billion initial capitalization — if, that is, the United States and other key countries now follow suit. Only then can the fund get to work on its vital mission: to make strategic, paradigm-shifting investments that spur low-carbon growth and climate resilience in developing countries.

The need for such immediate investment is clear. The International Energy Agency found that global investments in clean energy technologies and energy efficiency must double to nearly $790 billion per year by 2020 — and increase to $2.3 trillion per year by 2035 — in order to avoid dangerous levels of warming. In addition, the World Bank determined that the cost for developing countries to adapt to even moderate warming will be at least $70 billion to $100 billion per year through 2050, which is over three times the current estimate of global adaptation investment.

You can probably guess what the problem is: Only Congress can appropriate money, and the House of Representatives is controlled by Republicans, who don’t accept climate science and want to cut spending on both foreign aid and environmental protection. In February, congressional Republicans dismissed Obama’s suggestion for a domestic climate resilience fund by noting that it was snowing.

So when it comes to helping the developing world grapple with climate change, Obama is left with nothing to do other than spend the little money he’s got more carefully.

—–

*Correction: This post originally stated that the Overseas Private Investment Corporation provides loan guarantees worth some $30 billion annually. In fact, in 2013 OPIC provided financing and insurance commitments worth $3.9 billion.