To offshore drilling advocates, the oil-soaked birds washing up on the Gulf shore are a regrettable sacrifice in our pursuit of a higher calling: energy independence. Oil is a nasty business, they admit, but to them, offshore drilling is better than continuing to buy our oil from hostile countries like Iran, Saudi Arabia, and Venezuela.

They imply that we have a choice between dirty bombs and dirty oil.

Nothing could be further from the truth: offshore drilling has never and will never make us less reliant on Saudis, Iranians, or Venezuelans. Whether we like it or not, oil from those countries is cheaper and in many ways cleaner than oil from deep under the sea — and until that changes, Americans are going to continue to use it.

A lot of that is because of basic geology. It’s easy to get oil out of the Saudi desert and other parts of the Middle East. Middle Eastern oil tends to sit in immense, highly concentrated pools close to the surface. Even though many Saudi oil fields have been in production for decades, there’s still loads of oil left. More oil comes from a single Saudi field, the Ghawar, than every country except the United States and Russia — even though Ghawar has been in production since 1951.

In the United States, however, all the cheap oil is gone. We’ve been sucking it out of the ground for a hundred years. Pretty much all that’s left is way down deep under the sea or in highly depleted wells that only wildcatters will drill. It’s unpredictable, exploration frequently comes up dry, and because it requires sticking so many holes in the ground, accidents are more likely. Scraping what’s left out of the ground and bringing it to gas stations is dangerous and costly.

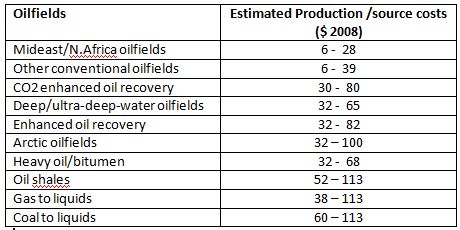

Although oil companies are notoriously chary about sharing their production costs, the International Energy Agency recently published the results of a global survey based on published data and leaks from industry insiders.

Source: International Energy Agency World Energy Outlook 2008 (28 July 2009)

What they found was unsurprising to oil industry insiders. Given the easily accessible geology and the still-plentiful supplies, Saudi oil clocks in at just four to six dollars per barrel, with similar costs for other sources of Middle Eastern oil like Iran and Iraq. With relatively mature fields, Venezuelan oil costs about $20.

But it still beats out oil from the Gulf of Mexico and other offshore areas of the United States, which cost a comparatively whopping $32 to $65 dollars per barrel to produce, according to the IEA. Even when you throw in transportation costs of about two dollars a barrel to get oil from the Persian Gulf to the United States, Saudi oil is still just a quarter of the cost of offshore U.S. oil.

What this means is that no matter how many wells we drill in the sea floor, we’re not going to displace Middle Eastern oil. On the world market, buyers will always snap up the cheap, easy to get Saudi oil first and only then turn to whatever dregs come from America. It’s for this reason that when the price of oil plummets, domestic drilling operations become uneconomical and shut down, while the Saudis just keep on pumping.

At best, additional offshore drilling will displace other domestic sources of oil like the Alaskan Arctic and marginal Texan fields, and perhaps Canada’s tar sands, all of which cost even more than Gulf oil to get out of the ground.

As long as we’re using oil, it may not be such a bad thing to get so much of it from the Middle East, at least from an environmental perspective. Because the oil there occurs in such high concentrations, it requires far fewer holes to extract the same amount, dramatically reducing the risk of something going wrong. Even when there are spills, they have far fewer environmental consequences. It goes without saying that the mostly lifeless Arabian desert is not an ecologically sensitive fishery or Alaska’s wildlife rich coastal plain.

Of course, that doesn’t exactly make Middle Eastern oil clean, either. Burning it still produces enormous amounts of carbon pollution and buying it still funnels money to terrorist-friendly regimes.

So what are we to do? First, we have to recognize the truth that because of the economics, whether we like it or not, the last drop of oil our country burns will be Saudi oil.

So the way to end our reliance on oil in the Middle East isn’t to boost production of expensive and risky oil domestically – it’s to end our reliance on oil period. That means capping carbon pollution, raising fuel efficiency standards for cars and trucks, and investing in clean energy technology.

If we move aggressively to achieve that vision, one day soon we can celebrate the burning of our last drop of oil. It may be Saudi, but it will still be the last.