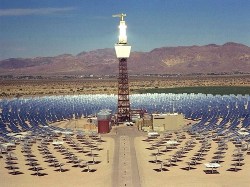

A concentrated solar plant in the California desert. (Photo by International Rivers.)

Currently the city of Los Angeles gets about one-fifth of its electricity from renewable resources. By the end of the decade this will increase to one-third. As the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power (LADWP), the largest municipal utility in the United States with over 4 million customers, slowly phases out coal and some natural gas, solar parks in the deserts to the east are filling the void.

Utility-scale solar offers the cheapest and most practical form of clean energy for Los Angeles. But the forecast is not all sunny. As these solar parks come into view, so does the range of associated concerns. On the Mojave National Preserve, Oakland-based BrightSource Energy Inc.’s Ivanhoe Solar Complex has made ongoing and exceedingly costly efforts to accommodate the fragile desert tortoise population. Earlier this year, the Genesis Solar Energy Project in Riverside County, Calif., was held up when Native American burial remains were found on multiple occasions during construction, indicating the presence of sacred burial grounds.

Donna Charpied, a 57-year-old farmer who’s lived in Desert Center, Calif. (an aptly named town of 200 an hour east of Palm Springs on the I-10), for 30 years, has a number of issues with her new — and only — neighbor. “My heart aches every time I look out my window and see the construction over there,” says Charpied, gazing out from her recently renovated trailer towards the barren Coxcomb Mountains that define the eastern portion of Joshua Tree National Park in Southeastern California. “It’s just unbelievable, the destruction.”

Music emanates from a nearby shed encircled by agricultural equipment in various stages of disrepair. With no neighbors for over a mile there’s little reason for noise control, let alone clothing, on this isolated plain of desert. At least there wasn’t until recently. The Desert Sunlight Solar Farm, a 550-megawatt, 4,000-acre project being developed by First Solar and co-owned by NextEra Energy Resources and General Electrical, passes within 600 feet of Donna and her husband Larry’s 10-acre plot. According to the First Solar project overview, the facility will create enough power for 160,000 average homes and displace 300,000 tons of CO2 annually, the equivalent of taking 60,000 cars off the road. Begun in September 2011, the project is less than one-fifth complete, but the Charpieds see it as a harbinger of the potential local impact large solar projects on public lands can have.

Los Angeles is far from the only region relying on big solar to reach renewable energy targets. The recently released “Programmatic Environmental Impact Statement for Solar Energy Development in Six Southwestern States,” prepared by the Bureau of Land Management in partnership with the Department of Energy, proposes 17 Solar Energy Zones (SEZs). Riverside East, which includes Desert Center, is the largest of the SEZs, which are meant to facilitate environmentally responsible utility-scale solar energy development. Proposed to be 202,896 acres (821 square kilometers), Riverside East’s western boundary is approximately 0.7 miles from Joshua Tree National Park.

“This is a whole new form of gentrification,” Charpied says, referring to the Solar Energy Zones. “If all these projects come to fruition, people will simply not be able to live here. This is all seems like corporate welfare to me.”

Water consumption is one of the main local impacts of desert solar projects. Even though water is not needed for generating electricity in all cases, the projects use water to keep the dust down and rinse the panels. In Desert Center, this water comes from deep reservoirs that get little to no regular groundwater recharge. According to Charpied, the water they use was carbon tested to be 10,000 to 30,000 years old. Another one of Charpied’s main concerns is increased dust from habitat destruction. She says dust storms have notably increased in the area over the last year, and may gravely impact her farming of jojoba, a native shrub that produces oil useful in the cosmetic industry, which she and her husband rely on for their livelihood. Charpied has also seen more animals on her property since construction started nearby, indicating increased competition due to decreased habitat.

Donna Charpied.

“I really wish Obama would’ve given out that stimulus money to do rooftop solar instead,” Charpied says. “Like they’ve done in Germany.”

Jonathan Parfrey, a commissioner on the LADWP board since 2009 and executive director of Climate Resolve, an advocacy organization that builds understanding of climate change in Los Angeles, sympathizes with the Charpieds’ plight.

“I’ve been out in the desert; I know some of the people being impacted,” Parfrey says of the solar projects from his 15th-floor office in the LADWP building in downtown L.A. “I’m an enviro, I want to conserve that land. But it’s not just as easy as saying L.A.’s got to slap solar on rooftops. There has to be a balanced approach.”

Parfrey readily acknowledges that awareness of the environment in which solar farms are placed is critical; ideally they would avoid recreational spots or wildlife-rich areas. But he also asserts that in order to move forward with regional clean energy goals, these industrial-sized projects are imperative — it’s just the way the economics plays out. Putting solar on residences and businesses is expensive, as each job is custom and requires boots on rooftops, a liability issue. At this stage in the game, decentralized solar generation can also lead to voltage problems and challenges with distribution balancing.

Aside from the practical issues, there are also social and political realities to consider.

“In my view the transition to clean energy has to happen as inexpensively as possible,” Parfrey says. “Otherwise people will rebel and they won’t even want to pay for it in the face of climate impacts. They will say, ‘That’s too bad about what’s happening to the environment, but I can’t afford to put food on my table because my electricity bills are too high.’”

According to Parfrey, the LADWP is experimenting with ways of doing rooftop solar inexpensively. A solar feed-in tariff program, in which both residential and commercial power producers can sign contracts for up to 150 megawatts of solar power for above retail rates, was established this year. He sees the transition to clean energy as a slow but steady and secure one, with distributed solar eventually playing a much large role. In the meantime the city of Los Angeles is doing what it can with the available resources.

“L.A. is a wonderful city, but it is, however, not a wealthy city,” Parfrey says. “Our tax base is relatively low per-capita and 20 percent of our population is at or below the poverty line. So we simply don’t have the resources that San Francisco or New York might have.”

As decentralized solar potential grows and solar technology improves over the next decade, how to store that energy will become an increasingly important question. And alongside that, the question of how big utilities like LADWP can adapt to a decentralized grid in which there may be temptation for customers to go offline.

“If I could have my moment like in The Graduate where he says to Dustin Hoffman, ‘The future is in plastics,’ mine is how do we do distributed generation where we maintain the utility business model and we’re able to provide continual service for people,” Parfrey says. “When we find the magic key to that I think it will be a revolution. I think it will really help affect the transition away from fossil-fuel energy sources.”