In the story of the blind men and the elephant, the trunky mammal is misidentified as a spear, a tree, a wall, a rope; the men are too siloed from one another to fully discern the animal they’re patting down. Today, the old metaphor from the Indian subcontinent is mostly used in corporate retreats and master’s of public policy programs to demonstrate the gains of synergy (or something thereabouts). There’s a new elephant lurking in the room, though, and its name is climate change.

A new report on the global risks of a changing climate, commissioned by the U.K. Foreign Office, suggests that we’re still mistaking the elephant for a spear. “In public debate, we have sometimes treated it as an issue of prediction, as if it were a long-term weather forecast,” writes Baroness Joyce Anelay, minister of state at the Foreign Office, in her introduction to the report. “Or as purely a question of economics — as if the whole of the threat could be accurately quantified by putting numbers into a calculator.”

It can’t, she argues. At the systemic level, we ought to be as serious about preventing climate change as we are about “preventing the spread of nuclear weapons.” In fact, taking systemic risks into account is the only responsible way to prioritize a national agenda in the face of competing goals (say, economic growth or reducing unemployment), writes Anelay.

She calls this approach a “holistic assessment.” The report released today is the U.K.’s first attempt at this type of risk assessment — and the account is bracing. Written by a team of science and technology policy and international security experts from the U.K., the U.S., India, and China, the report highlights the climatic, water, food, economic, security, and ethical risks of climate change, and importantly, how these risks interact with one another.

As the report’s accompanying policy brief points out, there are three main questions we should be asking:

- What are we doing to the climate?

- How might the climate change in response (and what could that do to us)?

- And what, in the context of a changing climate, might we do to each other?

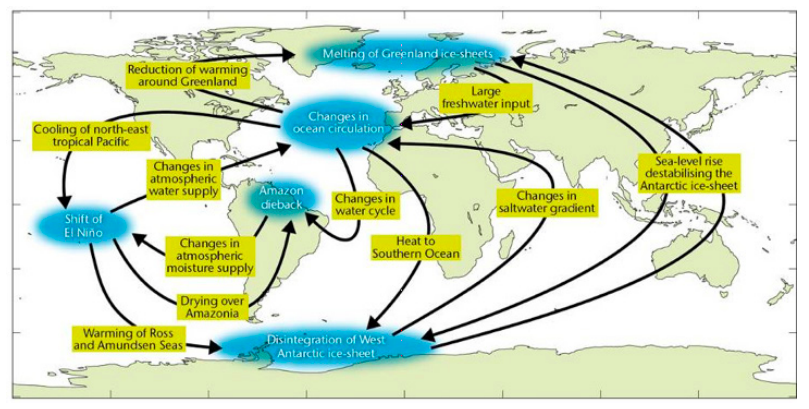

Here’s a hint at an answer to the second question:

The feedback loops pictured above can make quantifying the effects of climate change a hideous, highly uncertain endeavor.

It’s the last question that’s most difficult to answer, though, and it’s the one that keeps national and international security experts up at night. As crop yields drop and water shortages increase, political and ethnic instabilities are only amplified. Among many other risks, this can lead to more successful terrorist recruitment, the authors argue. Climate change is also expected to force whole swathes of populations into cities. When migration becomes “more a necessity than a choice … the capacity of the international community for humanitarian assistance would be overwhelmed,” write the authors of the report.

Failure to take these risks into account could spell dire security consequences, they write. “If policymakers, under the guise of ‘waiting for perfect information’, fail to set strong climate change mitigation and adaptation policies today, they are ignoring the risks to our economy and our national security for the future,” stated the report.

The Foreign Office report follows similar sentiments expressed by the Catholic Church and the Church of England. “Climate change is both a driver of conflict and a victim of conflict, and we must face that reality and use our networks to address that issue,” said the Archbishop of Canterbury Justin Welby at a debate on Monday in York, England. He also called for a “holistic” response to climate change.

“This is not a standalone issue,” argued Archbishop Welby. “It cuts across all we do.”