The seemingly endless and often torrential rains that deluged Texas and Oklahoma in May are in some ways a harbinger of what the South Central states can expect to see as the world warms. But the region also could be in store for just the opposite — more long bouts of hot, dry days that could cause the Southern Plains to be even more susceptible to drought than they already are.

The juxtaposition between these trends is an example of the complex and sometimes unpredictable way that climate change signals come together. Some trends are well known while others have yet to crystallize. The trend toward heavier localized downpours is a solid tenet of climate science, as is the fact that overall higher temperatures will exacerbate any droughts that do occur. But whether the boom-and-bust cycle of drought and flooding seen over the last five years is what the future will look like is much murkier.

“The question is: Are we seeing the new normal?,” said Victor Murphy, climate services program manager for the National Weather Service’s Southern Region.

Rains that fell for days on end, and sometimes in astonishingly intense bursts, made May the wettest month on record for both Texas and Oklahoma with many locations recording 15 to 20 inches for the month. Areas in some cases saw up to 500 percent of their normal rain for the month, wiping out the years-long drought.

Several cities in both states broke records for the most consecutive days with rain, as well as for daily and hourly records, with several inches falling in just a matter of hours in some places, leading to serious flash flooding.

Both climate models and the basic physics of the atmosphere show that such highly concentrated bursts of rain are something the world on the whole will see more of in the future. As the atmosphere warms because of the increasing heat trapped by accumulating greenhouse gases, the air can hold on to more moisture. So when it rains, there’s more fuel to throw on the fire, so to speak.

“I think everyone’s pretty much in agreement with that,” Murphy said.

[tweet https://twitter.com/GCarbin/status/605079085614637056]This effect of warming has already been observed across the U.S. The trend has been most pronounced in the Northeast, which has seen a 71 percent uptick since 1958 in heavy precipitation events, according to the National Climate Assessment released last year, but it has also been observed in the Plains, where such events have increased by 16 percent.

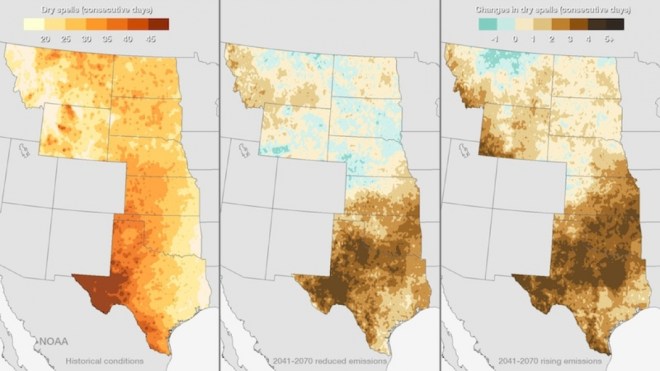

But climate models also suggest that the region could see more consecutive days with no precipitation, up to five more days a year by mid-century, according to the NCA. Longer dry spells can lead to increased odds of drought developing.

Texas state climatologist John Nielsen-Gammon isn’t completely sold on that projection because of limitations in the models and a lack of a clear signal of increased drought odds so far. But “it’s certainly possible,” he said.

One way warming will assuredly impact future droughts is in the higher average and extreme temperatures it will, and already has, brought. A tenacious heat wave in 2011 helped plunge the Southern Plains into such a deep drought. Higher temperatures mean both increased evaporation and higher water demand from people, plants, and animals, which can exacerbate any drought that develops from the natural variability inherent to the region.

The number of days with the hottest temperatures, which can reach above 100 degrees F in Texas and Oklahoma, could rise by up to 20 days by mid-century, according to the NCA analysis, even under scenarios of low future greenhouse gas emissions.

While the possibility of more, and more intense, drought may seem to be at odds with the trend of more heavy downpours, they are both possible in a warmer world. While conditions in the Southern Plains may tip drier overall, with rain coming less often, when it does rain, “you’re going to get more intense rainfall occurring over shorter periods of time,” Murphy said.

The number of additional dry days expected in the future under low and high greenhouse gas emissions scenarios compared to historical averages.NCA

The implication of these dueling trends is that the region needs to be prepared for both. From the perspective of the increased odds of drought, Murphy said that one clear way to be better prepared is to keep in place some of the reasonable conservation measures enacted from the state to local level over the last few years, “making conservation part of our everyday lives.”

In terms of being better prepared for heavier rains and flash flooding, some of that comes from better forecasting and water management, Murphy said, as well as making sure that new infrastructure in a state that has seen considerable growth in recent decades is built to better deal with such onslaughts. Much of the existing urban areas are covered in impermeable concrete and asphalt, leaving nowhere for water to drain.

“There’s myriad ways of dealing with both the wet side and the dry side of what we’re talking about,” Murphy said.