This story was originally published by Mother Jones and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

There was a time not so long ago when getting a LEED certification on a new building was a big deal, a relatively rare badge of architectural pride. LEED — which stands for Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design — is a suite of architectural metrics for things like energy and water conservation. These days, it’s the most common standard for designating a building as being environmentally friendly. As nationwide spending on green construction has soared, LEED certification has become almost par for the course.

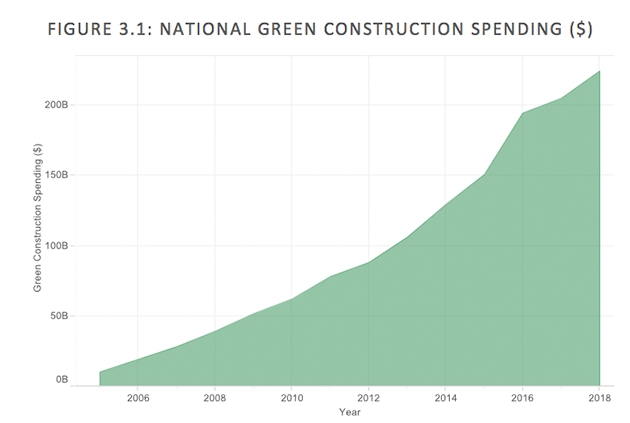

According to a new report from the U.S. Green Building Council (USGBC) — the nonprofit behind LEED — the green construction industry expanded 15-fold in the last decade and is now growing faster than non-green construction. In 2014, roughly $129 billion was spent on green building projects, including both LEED-certified buildings and buildings that meet an equivalent environmental standard:

USGBC

That’s still only a small chunk of the $962 billion spent in total on construction projects in the U.S. last year. But it’s a happy trend, since buildings are one of the biggest energy hogs out there. In the U.S., nearly 40 percent of carbon dioxide emissions can be traced back to energy used in buildings. Green architecture aims to reduce that footprint by going after energy and water efficiency at every stage of design, from the building’s shape and orientation to what kind of lightbulbs it uses. According to the report, green buildings have offset greenhouse gas emissions by an amount equal to taking nearly 2 million cars off the road (more on that below). And there are tangible benefits for building owners: By some estimates, spending 2 percent more upfront on green design features pays back up to 20 percent of the total construction cost over the building’s lifetime.

Architects and their clients are taking note, said Craig Schwitter, a professor at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Architecture who wasn’t involved with the report.

“Green building is taking over a significant portion of construction,” he said. But just because we’re spending more on LEED buildings doesn’t necessarily mean we’re saving the climate.

There are a few caveats to keep in mind with a report like this, Schwitter said. First of all, putting the LEED stamp on a building doesn’t necessarily mean it’s all that climate-friendly. When Bank of America unveiled its new office tower in Manhattan in 2010, it was heralded as the first LEED Platinum skyscraper, a model for sustainable urban design (netting nearly $1 million in state tax credits for the accomplishment). But a couple years later, when the city released an inventory of its greenhouse gas emissions, the BoA building was one of the worst culprits. The problem, Schwitter said, is that not wasting energy isn’t the same thing as using less of it. A building can meet all the green or LEED credentials in the world, but still draw huge amounts of power — and thus have a massive carbon footprint — as the BoA building illustrated.

“It’s not that we’re saving the energy, it’s just that we’re being less wasteful,” Schwitter said.

Moreover, he said, we should approach stats on green buildings’ energy benefits (like the one above about cars) with caution, since it’s hard to find a hard, objective baseline for comparison. It’s hard to prove, before a building is built and occupied and in use, what its energy footprint would be like with and without various green attributes. And Schwitter said it’s not uncommon for architects to err on the side of making the “not-green” option look as bad as possible, to play up the green benefits. So while this USGBC is an interesting starting place, I would want to see an independent peer-reviewed assessment before taking these stats as gospel.

Still, it’s definitely true that architects are dealing with more and more clients who demand high standards of environmental design, Schwitter said. The boom in green building is unlikely to reverse anytime soon.

“It’s very rare that we do a building that doesn’t have a LEED rating,” he said. “It’s rare to find a building owner who says, ‘This is all crap, we don’t need this.'”