About 13 gigawatts worth of coal-fired power plants are closing this year to comply with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Mercury and Air Toxics Standards (MATS) rule.

What’s your reaction?

A) This is a necessary first step in the evolution away from coal to cleaner renewable energy sources.

B) The plants are only the latest victims of President Obama’s war on coal.

C) Any one closure leaves a hole in the fabric of the community, economy and local government budget.

D) These dinosaur plants have been dying of old age and obsolescence, not from blows inflicted by the EPA.

If you answered A, you may be a member of the Sierra Club’s “Beyond Coal” campaign, which seeks to retire at least a third of the more than 500 coal plants within the U.S. by 2020.

If B, you may be a congressman from Appalachia. Of the 13 GW being retired, 8 GW comes from plants in Appalachia—a region represented nearly exclusively by Republicans in Congress due in part to anxiety over the coal industry and the resulting success of “War on Coal” messaging.

If C, you may be a local elected official or government staffer desperate to build economic momentum in a rural, mountainous region that’s long struggled to retain local talent and keep pace with larger metros.

If D, you may be R.L. Miller.

From a national perspective, these plants represent a fairly small chunk of the nation’s overall electrical capacity. For the communities in which they’re located, however, their closures mean much more than just a smaller carbon footprint: The resulting loss of jobs and local tax revenue leaves an economic void as well. And then there’s the question of what to do with these plants, many of which sit on land that, if it can be properly cleaned up, could be valuable for redevelopment or recreation.

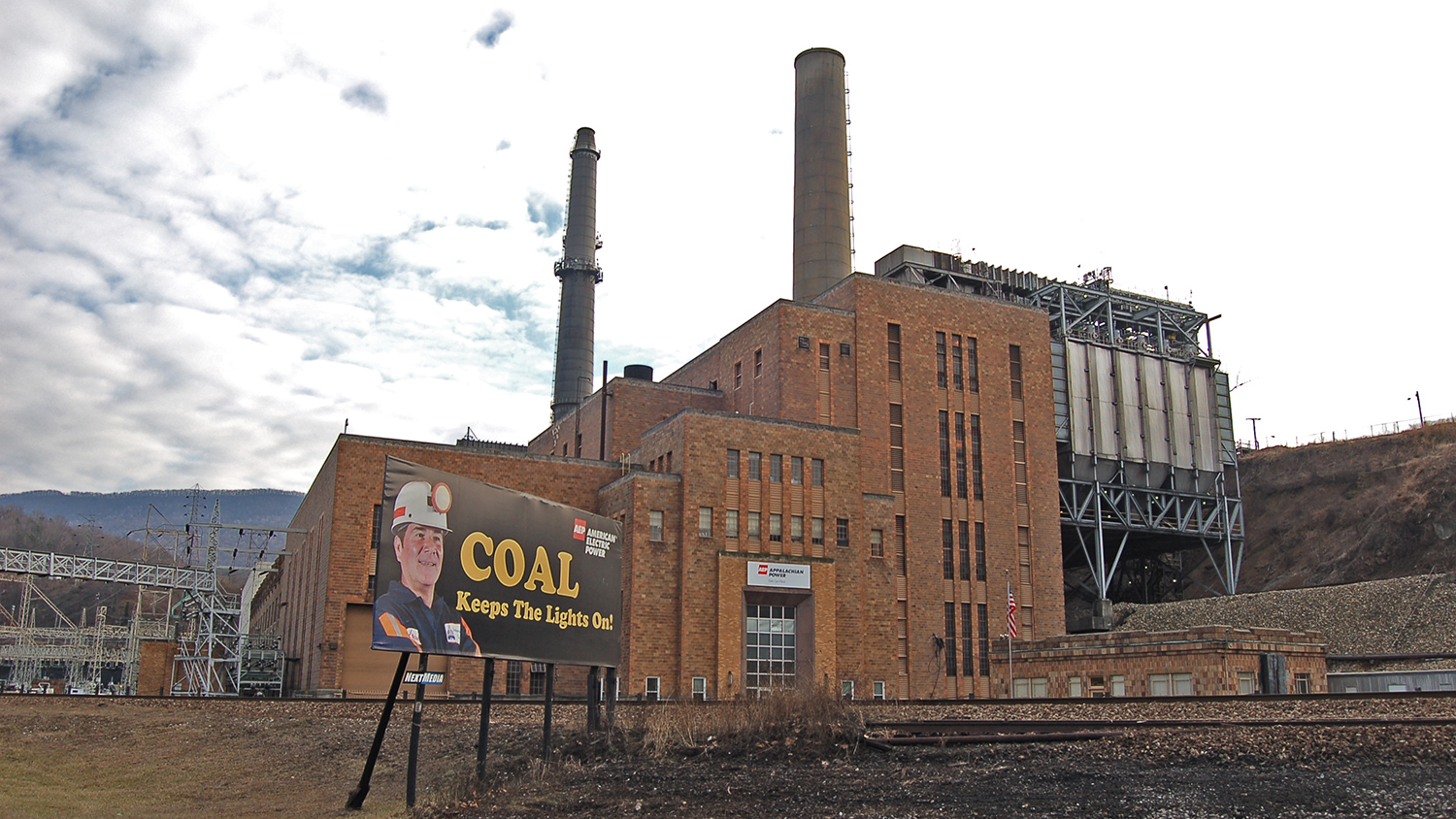

Consider American Electric Power’s (AEP) plant in Glen Lyn, Virginia, a tiny town once known as Hell’s Gate that sits near the West Virginia border. The 96-year-old plant is one of seven AEP plants to be shut down by May 31. (Another two plants will be converted to burn natural gas.) All told, AEP is retiring more than 6,000 megawatts (MW) of coal-fired generating capacity.

Only 31 people worked at the Glen Lyn plant, but then, the town has a population of just 115, according to the U.S. Census. The plant’s employees and retirees are an “integral part of the community,” says Giles County Economic Development Director Chris McKlarney. “You can never replace that.”

The loss of local tax revenue will leave a $440,000 annual gap in the county’s budget, a significant chunk for a county with fewer than 17,000 residents. “It will take a combination of cuts to expenditures and many years of steady growth to overcome this shortfall,” McKlarney says.

In his 2011 story for Grist on the planned closures, Miller used Glen Lyn as his Exhibit A, and indeed the plant is aging and little used within the larger context of AEP’s fleet. It dates back to 1919, and one of its two remaining units is the oldest in the country. Unit 5 went online in 1944 at the height of World War II—which meant that, due to brass shortages, manufacturer General Electric used a nameplate made of lead. The other unit is no spring chicken either; it went into service in 1957.

For several years, AEP has only used Glen Lyn during peak times when it needed extra capacity, says company spokesman John Shepelwich. The MATS regulations accelerated its closure, but due to its age, it likely would have been shut down within the next decade anyway. The plant burned through its final loads of coal in April and is now going through the exhaustive process of permanently shutting down. As you might expect for a facility that’s been burning coal for nearly a century, that involves a lot of environmental remediation work.

AEP has been shipping Glen Lyn’s coal ash to a site in West Virginia for several years, so most of its ash ponds have already been sealed. Most of its employees have transferred to new jobs elsewhere. Those who are left are busy cleaning up a variety of oils on the property, evaluating equipment for risks and potential reuse, and generally mopping up.

The site does boast several features that could make it attractive from an economic development standpoint — it sits on a river, has rail line access, and is fairly close to Interstate 77 — but it’s dirty-fuel history also poses potential challenges.

“There’s the possibility the whole facility could be razed, or it becomes a site for other construction or a brownfield or a reclaimed property,” Shepelwich says. “There are so many things that could happen, but it all is based on what’s the most affordable thing for us to do — what will not impact the company or customers in a negative way.”

At a time when cheap natural gas is creeping up on coal in terms of overall electricity generated — the U.S. Energy Information Administration projected earlier this month that power generated from the two will temporarily converge this spring — AEP still relies more heavily on coal that most utilities. That’s changing, though. In 2014, coal accounted for 69 percent of AEP’s power, a significant drop from even a few years ago. The company projects that figure will fall even further, to 45 percent by 2026.

That’s a shift in the right direction, says Mark Kresowik, a Beyond Coal deputy director: “We’ve got to phase out fossil fuels from electric sector as quickly as possible.” But to U.S. Rep. Morgan Griffith, the Republican who represents southwest Virginia, including Giles County, it’s a dangerous shift that creates the potential for rolling brownouts if that capacity isn’t replaced.

Both agree, however, that the MATS-related plant closures carry the potential to further disrupt the Appalachian communities where they’re based.

“When you’re talking about Narrows, that’s a big chunk of money that won’t be there to buy a sandwich, buy a car, whatever they might do,” Griffith says. “It’s a real loss.”

Kresowik admits the closure will affect jobs and taxes, but says the way forward is not to preserve a dirty, outdated industry, but instead for state and federal government to invest in programs to create new economic opportunities.

“A lot of these facilities are on rivers, and typically there’s some interesting recreational access or other potential economic opportunities at these sites,” Kresowik says. “It takes a couple of years to clean them up and prepare them for that.”

Utilities continue to build new power plants but they’re powered by natural gas or renewable energy. In Virginia, Dominion announced that its Virginia City Hybrid Energy Center, which opened three years ago, will be its final coal-fired power plant. It closed a coal-fired plant in Chesapeake last year and plans to build both natural gas and solar-powered plants within the next decade. In North Carolina, Duke Energy plans a natural gas facility to replace its 51-year-old coal plant at Lake Julian, near Asheville, which will be shuttered and demolished.

AEP currently has no plans for new power plant construction, but when it does, it will almost certainly not be powered by coal.

“If we need some kind of baseload or a peaking plant, it would be a natural gas plant,” Shepelwich says. “The cost of construction for a natural gas plant is much lower than a coal plant.”