Andreas F. Borchert/Wikimedia CommonsScientists have found that drought means Engelmann spruce trees (pictured on Red Mountain Pass, Colo., above) have weaker defenses against spruce beetles, triggering an outbreak in hundreds of thousands of acres in Colorado’s forests.

Since the late 1990s, mountain pine beetles have swept through millions of acres of forest in the Rockies, turning hillsides of trees a rusty red and then grey as they populate trees and kill them. In Colorado, this outbreak seems to have peaked in 2008 and 2009; but just as one species slowed, another — the spruce beetle — has picked up steam. A new University of Colorado study published in Ecology reveals how drought was the driver of the rise in spruce beetle activity and resulting tree deaths in Colorado’s high-elevation forests in recent years. The drought is in turn linked to changes in sea surface temperatures that are expected to continue for decades to come. In the long-term, such massive insect infestations could dramatically diminish North American forests’ ability to retain water and sequester carbon — meaning trees will be less effective at balancing out the human toll on the environment.

So far, fewer acres of trees have been affected by spruce beetles than mountain pine beetles, but there are more spruce forests in Colorado than Lodgepole pine, so there’s “no reason to expect the percentage mortality to be less or acreage affected to be any less” than it was for the mountain pine beetle epidemic, said Tom Veblen, coauthor of the study and a geography professor at CU.

Lead author Sarah Hart remembers flying over British Colombia in 2007 and seeing endless stretches of red trees killed by mountain pine beetles. When she moved to Colorado, a spruce beetle outbreak had started to turn heads in the area, prompting her to look deeper into its underlying causes.

To analyze what was driving the recent spruce beetle explosion, the CU researchers compiled a 300-plus-year record of past outbreaks using tree ring data and historical documents like records from surveyors in the early 1900s. Warmer temperatures allow beetles to speed up their life cycles and expand in numbers. But “it was interesting that drought was a better predictor for spruce beetle outbreaks than temperature,” said Hart. Trees have natural defenses against these beetles; for one, they expel intruders with resin. During wetter periods like 1976-1998, the CU researchers noticed, spruce beetle outbreak was minimal because trees were likely more successful in pitching the beetles out, even as the bugs prospered in the warmth. Drought appears to weaken the trees’ defenses, making even healthy-seeming spruce susceptible to beetles desperate to get inside to feast and lay eggs. Since drought is likely to linger in the Southern Rockies in the near future, conditions are ripe for the beetles to continue their reign.

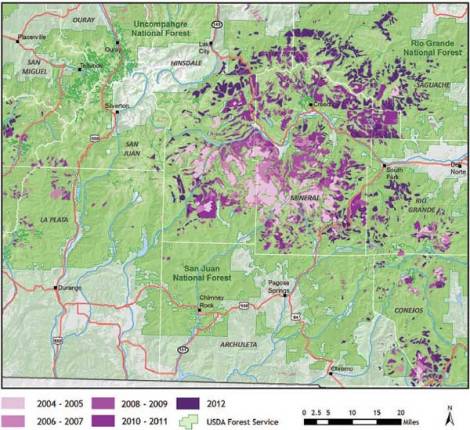

Colorado State Forest ServiceThe spruce beetle’s march on southwestern Colorado, 2004-12. Click to embiggen.

Previous forecasts of spruce beetles had focused on studies of the insects in lab settings. It’s harder to study these outbreaks from the perspective of the tree, says Hart, because “you can’t just take a tree and put it in drought conditions in a lab.” Hart’s study overcame that by using historical data, but the researchers still aren’t sure of the exact mechanism that makes it harder for trees to repel bugs during drought. They theorize that during drier periods, trees don’t photosynthesize as much in order to conserve water. This may lead to the tree producing fewer of the compounds that normally equip it to defend itself against insects.

Shifts in sea-surface temperatures also lead up to the outbreak. In the 1990s, we entered a warm phase of Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO), which has been linked to warmer and drier conditions across the country (the Dust Bowl occurred during the last positive AMO stage, for instance). This set the stage for spruce beetles to go haywire, especially in more vulnerable forests. What could be different this time is that the recent rise in temperatures associated with AMO is coupled with global warming trends, Hart explains, meaning forests facing down spruce beetles have quite a battle ahead.

More than 311,000 acres were killed by spruce beetles in Colorado in 2012, compared to 64,000 acres in 2008, and infestations are going strong, especially in southern parts of the state like the San Juan and Rio Grande National Forests. The map above shows areas impacted, as documented by aerial surveys done by the U.S. Forest Service and the Colorado State Forest Service.

The study’s findings call into question other theories about why bark beetle outbreaks happen. Some have blamed the infestations on fire suppression — that because we haven’t allowed for enough fire, we’ve increased stand density and made trees more vulnerable. “I don’t think that’s true,” says Hart, “because over the last 300 years, climate has been such a strong indicator of these outbreaks.” Managing to try and prevent these beetle explosions is “kind of a lost cause,” says Hart, adding that resources are probably better spent on regeneration efforts.

This story was produced by Mother Jones as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

This story was produced by Mother Jones as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.