This story was originally published by Mother Jones and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

Kids are a vital part of the climate change conversation; they’re the ones, after all, who have to live in the world the rest of us are screwing up. But if they go to a public school, they could be getting a very confusing education on the subject.

On Thursday, researchers published the first peer-reviewed national survey of science teachers on whether and how they teach about climate change, in the journal Science. The survey, which covered a representative sample of 1,500 middle and high school science teachers from all 50 states, found that classrooms often suffer from a problem also common in the media: the false “balance” of giving equal weight to mainstream climate science and climate change denial.

Science teachers, the study found, have a better grasp of the most basic climate science than the general public: 67 percent agreed that “global warming is caused mostly by human activities,” compared with about 50 percent of all U.S. adults. And most do include some mention of climate change in their lesson plans: 70 percent of middle school teachers and 87 percent of high school teachers spend at least an hour on global warming each year.

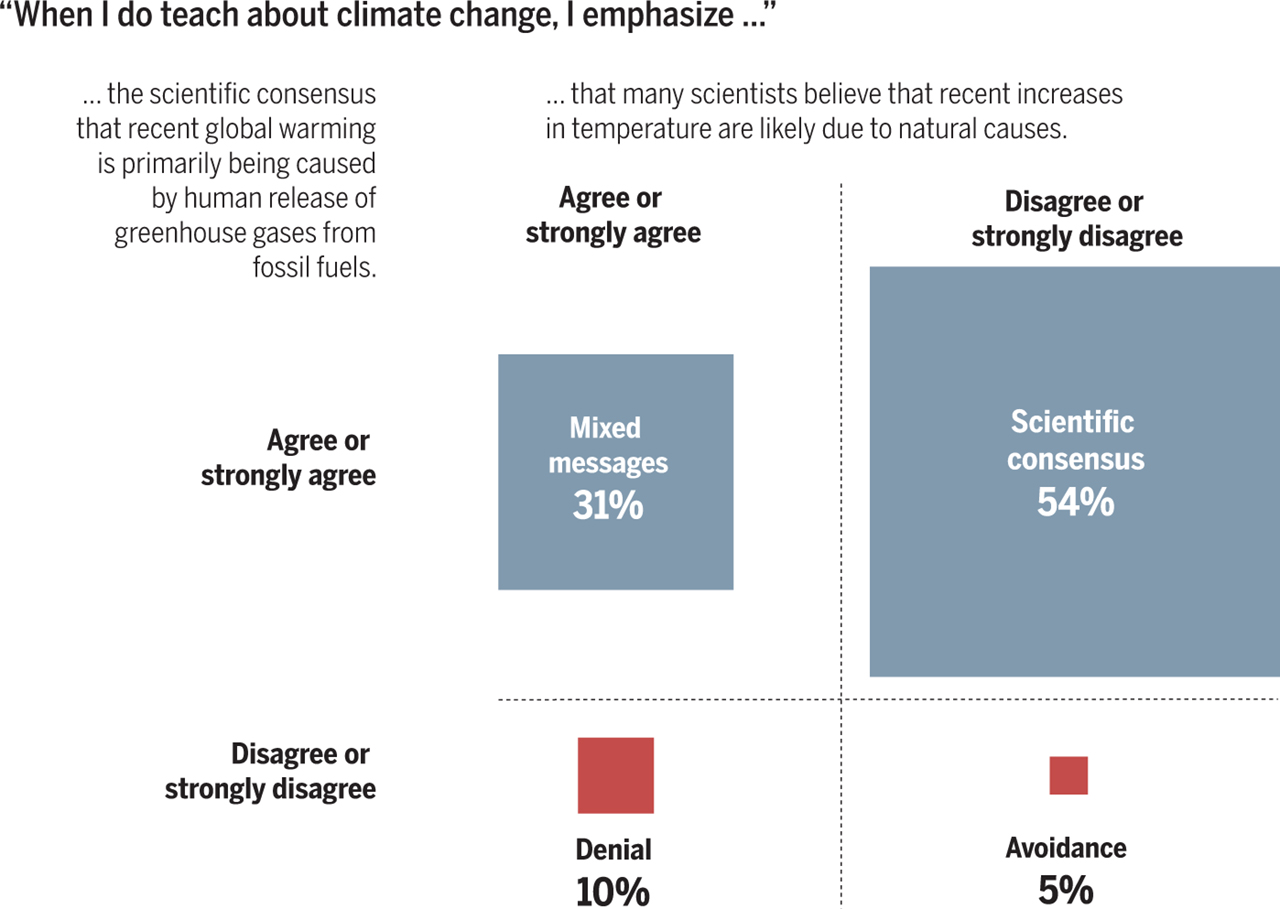

But the quality of those lesson plans is inconsistent. One-third of the teachers said they emphasize that global warming “is likely due to natural causes,” and 12 percent specifically downplay the role of human causes. One-third also “report sending explicitly contradictory messages,” simultaneously presenting opposing explanations for humans’ role in recent temperature increases. The chart below, from the study, shows that while most teachers’ lessons align with mainstream climate science, many offer their students conflicting or incorrect messages:

Plutzer et al, Science 2016

Perhaps most distressingly, most teachers are unaware of how many scientists agree that climate change is mostly caused by humans. Only 30 percent of middle school teachers and 45 percent of high school teachers agreed that the consensus was in the range of 81 to 100 percent. (It’s about 97 percent.)

“What’s surprising is that many teachers personally think humans are the culprit [for climate change], but they are unaware that scientists share their views,” said Eric Plutzer, a political scientist at Pennsylvania State University who was the study’s lead author.

There are a few possible reasons for this, Plutzer explained. One is that climate science is usually not a part of teacher training curricula at colleges and universities. But teachers are also caught between competing sources of pressure. Because many standardized tests don’t feature questions about climate change, there’s little incentive to spend time on the subject. And teachers’ access to quality materials can be limited: Science advocates in Texas, for example, lost a battle in 2014 to keep climate change denial out of textbooks (although the study didn’t find a meaningful difference between liberal- and conservative-majority states). Teachers also bring their own preconceived prejudices that can align with the general political polarization about climate.

“Those teachers who are more on the small government, free markets, less regulation side of the [political] scale were the least likely to be aware of or accept the scientific consensus,” Plutzer said. “And they were the most likely to introduce mixed messages.”

It’s too early to say whether teachers’ climate lessons are improving or not; this is the first study of its kind. Minda Berbeco, programs and policy director at the National Center for Science Education and a coauthor of the study, said the survey’s aim wasn’t to single out teachers.

“I think in some ways [the survey] is disappointing,” she said. “But this is really a professional development opportunity. It’s clear [teachers] aren’t getting the access they need. Let’s start trying to correct that.”