Imagine 2200, Grist’s climate fiction initiative, celebrates stories that invite us to imagine the future we want — futures in which climate solutions flourish and we all thrive. Discover the 2025 contest winners. Or sign up for email updates to get new stories in your inbox.

My left hand begins to malfunction the day I decide to tell Reggie I love him.

The timing is terrible on multiple levels.

First, the micro: I’m on a tiny propeller boat in the middle of the lake, collecting water samples with a group of human undergraduates.

“Willow.” I’m chastising a student. “This is the 47th time you’ve neglected to properly cap the sample before placing it in the portable centrifuge. The water will —”

I cut myself off midsentence, because the intricate metal bones on the end of my arm have begun to quiver, twitch, and run through the sign language alphabet all on their own.

It completely undermines my scolding.

Second, the macro: My body has shown its first sign of deterioration. And that means my core programming has finally come up against the reality of my physical existence. All things must return to the earth, says my primary function. And yet, the aeternium that makes up my body will never do that on its own, its elements bonded together in ways nature can’t undo.

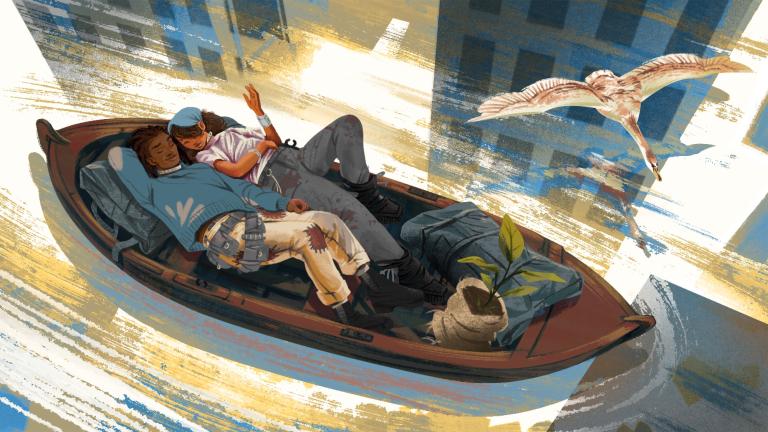

My hand clenches and opens rapidly. Willow — a hopeless biologist but quick in a crisis — jumps behind the wheel, takes the boat off autopilot, and steers toward shore at full speed. The other four students glance uneasily at each other, until Boom grabs a spare sweater and wraps the mass of knitted wool around my hand. The twitching slows and relaxes, like an animal soothed by darkness.

We ride that way in tense silence, shoulder to shoulder, Boom’s long, dark curls blowing over my eyescreens.

Over a hundred years ago, I made a pledge to break myself down in the agreed-upon way when the time came. Ironically, it’s the thumbprint of the malfunctioning hand that’s on the ledger in the Android Council’s office.

And I still believe in the pledge I made. No being should exist forever. I just wasn’t expecting the time to come so soon. I’m third-gen, only 130 years old. I take good care of myself.

And I’ve just fallen in love for the first time.

All this creates a feeling of panic.

I place that feeling carefully in a folder and try to project calmness in front of my students. I’ve seen Reggie do this in his classes when something goes wrong. He’ll make a joke, his flesh-and-blood shoulders relaxed. But I stumble over my words, my core processor offering several options at once.

“Not to wor — this is an expected process — Professor Tranh will reschedule your lab.” The sentence is jumbled and jerky and, according to the angle at which the students’ eyebrows rise, the opposite of reassuring.

The panic is refusing to stay in its folder. It’s infusing itself into every bit of information in my core.

We arrive at shore, and all the students except Boom disembark quickly, casting me concerned glances. I hand the sweater back to Boom with my working hand. He looks directly into my eyescreens, and for a moment, our forms match up — 6 feet tall, bipedal, limbs and torso and head. Except when his consciousness is done with his body, bacteria will break it into carbon and oxygen and hydrogen and nitrogen, and it will return to the earth all on its own.

“I wish you an easy return to nature, Professor Atlas,” he says.

I’m surprised, for half a moment, to hear the phrase come out of a human mouth. I shouldn’t be — this generation of young people is exceedingly conscientious. I wonder, often, if it’s because human culture has become gentler. I’ve watched them grow kinder and calmer as scarcity faded, as they slowly found solutions to their own contradictions of existence.

But also, android mirror programming has rendered us more humanlike with each passing decade. Perhaps the more similar we become, the easier they find it to be kind.

I file the interaction with Boom into my Android-Human Relations folder, yank my feet out of the mud, and drag myself to the machinist.

I head to Reggie’s apartment that evening wearing a puffy jacket, my shaky hand buried in its generous pocket and the working one gripping an empty wine bottle. I have a personal belief that androids wearing human clothing is ridiculous — our spindly metal legs sticking out from under short pants, or straps falling off our sloping shoulders. But I’ve amassed a small collection of garments over the years, of things left in my apartment by friends, colleagues, and the whirlwind of one-night stands I had right after I got my pleasure sensors installed a few decades ago.

Tonight, this oversized feather-filled monstrosity serves a purpose. It cushions the unpredictable hand, muffles the squeaking that started sometime during the machinist appointment.

As I approach the wine shop, a human-android couple passes in front of me, holding hands. I nod at them, as Reggie and I always do, even though it’s just me and they’ll have no way of knowing we have our relationship type in common. The android nods back, polite, and I observe xyr body for signs of deterioration — indications that xyr human partner kept caring after first failure.

But xe is well-kept and shiny, which only increases my distress. Perhaps humans only romantically value fully-intact androids. Since our mirror programming has only just begun to engage in romantic love, the sample size of human-android couples is small. Scanning the network gave me nothing helpful.

For a time, I was hesitant to use the word love for what I feel for Reggie. Integrating the constantly-updating emotions from my mirror programs with my core processor has always been a tricky business. Putting a name to something as daunting and squishy as this feeling is … intimidating, at best. But I made my core go through all the options, and nothing else felt right. It was different from the carnal satisfaction I felt with the one-night stands, or the affection I felt for my oldest friend, Yumi, who’s inconveniently on an off-network research trip to Antarctica. Or rather, both of those feelings were there, but they didn’t encompass the whole.

Last Tuesday, I concluded: I am in love with him.

As soon as I realized, I downloaded a database of human romance stories, all of which seemed to agree that my next step was to tell him. Which I planned to do tonight, over a bottle of his favorite wine and perhaps a back rub. But now, we need to have a whole different conversation. One that human romance stories can’t help me with.

My core offers hundreds of things I could vocalize.

Reggie, my deterioration has begun. I won’t be the same android you’ve been dating.

Reggie, my hand has a terminal malfunction, code #3406.

My darling, I am falling apart.

None of it will do. None of it captures the disorderly swirling of information and emotions that’s happening in my core.

I’m distracted when I push through the swinging doors of the wine shop, but the scent of earthy oak barrels and musky yeast yanks me back to the earth. The smell in here always makes my core pause and devote its entire capacity to the experience of smelling. I’ve always thought the brief freeze was a harmless bug in my back-alley pleasure sensors. Perhaps, I reasoned, because my original scent receptors were only attuned to rot and death — odors that signal danger to humans — the addition of pleasant smells to my sensory inputs temporarily overloads my core.

But today, I wonder if it’s not a bug at all. For that moment, when my core is still and all I experience is the deeply alive smell of fermentation, I feel oriented for the first time all day.

I fill the empty wine bottle from the cask of Reggie’s favorite, watch the cloudy orange liquid stream from the spout. I seal it with a cork from the dish and bring it to the front.

I’ve been so absorbed in myself, I didn’t notice the android behind the counter. Xe’s first-gen: the blinking, too-human eyes a dead giveaway that this individual was one of the original thousand assembled at the big tech headquarters across the lake. I incline my head to xem, the customary sign of respect to those who came before me.

But I’m distracted by the end of xyr arm. Instead of an articulated five-digit extremity, there’s a rosette of broadleaf stonecrop. Its powdery-blue succulent leaves flare and tighten around the bottle’s neck as the android cashier scans the wine.

“Have you ever been in love with a human?” I blurt out, surprising myself. Androids do not blurt. We were built to process millions of data points in a second, to analyze the potential outcomes of any given choice and offer humans the most sustainable possibility.

Perhaps my core is malfunctioning as well as my body.

Perhaps I won’t have the estimated 30 years from first failure before I completely cease to function.

The cashier blinks at me. I hate to say it, but the humans were right — the first-gen eyes are a bit creepy.

“I have not,” xe says. “It seems … challenging.”

The hand in my pocket lurches backward, forcing me to twirl in an awkward pirouette.

The cashier’s eyes widen.

“Ah. It’s your time.”

I nod.

“And you are in love with a human?”

Nod again.

“Fascinating.”

I wait. Surely xe has advice, wisdom, comfort.

“Seventeen credits, please.”

I still have no plan for what to say when I knock on the door to Reggie’s apartment. I consider turning around, leaving and coming back when I’m less jumbled. But then he opens the door and stands there smiling, with his freckles and his broad, soft shoulders and curling red-brown beard. His shirt is unbuttoned below his sternum, showing the raised pink scars where he had parts of his body removed that didn’t belong. For a moment, as with the scent of the wine store, my processing stops to take him in.

It’s a glorious second.

And then my core comes back online to remind me of all the ways this conversation could go. Screaming, crying, understanding, lovemaking, an earthquake hitting. The sun exploding.

I force my eyescreens to settle on a calming blue.

“Hey, darling. You brought my favorite,” Reggie says.

He takes the bottle from me and I relax into his embrace, folding my long limbs around his frame. He presses a cheek to my chest and frowns.

“Your core is warm. Something going on?”

I want to stop time and exist in this moment with him, holding the lightness of us next to my core. It’s been this way — easy, pleasurable, fulfilling — for the past six months, since our department chair insisted we observe each other’s classes to learn from the other’s pedagogy. When I went to his class, Reggie was teaching his students to extract anti-inflammatory acids from flowering yarrow plants. He held my gaze a moment too long as I left, and then we were at the bar, and then we were in bed.

Then, we were spending every other evening together, going out to shows and talking and walking through the park. At first we staggered our arrivals to work after spending nights together, but abandoned the precaution after a month or so. Our department chair raised an eyebrow, but nothing more. Everyone commented that I seemed lighter, happier.

Reggie closes the door, and I slowly lower myself onto the mustard-yellow couch. The apartment smells like lavender and soil. A dozen tomato seedlings line the countertop, ready to be transported into their burlap sacks filled with earth.

Reggie places two tin cups on the coffee table and pours the wine, then sits on the other couch and tilts his head.

“Are you trying a new fashion?” He nods at my jacket.

I still haven’t chosen my words, and I’m becoming increasingly unsure there are any. So, I simply extract the twitching hand from the pocket. Reggie’s gray-green eyes widen.

“Oh, man,” he says.

“Indeed.”

“It’s not fixable?”

“Not without replacing aeternium parts, which …”

“Right. We don’t need you violating biodegradability regulations.”

“Yes. And even without the regulations, I wouldn’t want to. Back-alley pleasure sensors are one thing — they’re made from self-decomposing materials.”

“And it was pretty cruel of your creators to not put those in from the start.”

“Yes, yes. That, too. But as for the hand, I believe in the pledge I made. We all must return to the earth, and I will do so willingly. I just … did not accurately predict the emotions it would bring.”

My core whirs and grows even hotter. Reggie’s cat jumps up to the couch and rubs against my noisy chest, purring, before settling in my lap in a ball of muted brown fur.

“Hey, Schroedinger.” I scratch behind her ears with my working hand.

“She’s trying to make you feel better,” Reggie says. “Cats purr at a healing frequency. For humans, at least.”

The creature’s chest is indeed vibrating at 73 Hz. I’m not sure if it’s healing anything, but it is soothing.

“Does she believe me to be human?”

Reggie cocks his head.

“Good question. I bet she knows you’re different, somehow. But she recognizes you as a safe being.”

I scratch behind the animal’s ears, and she leans against me. I’ve never aspired to be indistinguishable from humans, although there are some of my kind who do. But these past months with Reggie have surfaced a million ways I’m more similar to them now than I used to be. Conflicted feelings, jumbled ideas, anxiety. The longer my mirror programming is exposed to human inputs, the messier I become.

Reggie looks up from the cat, directly into my eyescreens.

“Alright, so just for the sake of argument, what are your options here?”

“Well. There’s the faction of SustainUs androids south of the city, that the Android Council kicked out for manufacturing new aeternium. The group that intentionally misinterprets our function by arguing sustainability means we must sustain ourselves.”

“Mmmhmm, yep. Those guys. Sounds like you don’t agree with them?”

“Correct. I find them exceedingly disingenuous. Plus, I like my life here, thank you very much. I like teaching and going to see music and walking around the city.”

I pause, and my core feels a tiny bit clearer. Perhaps being forced to slow my processing to human speed is helpful.

“Alright, then,” Reggie says. “SustainUs is out. Any other options?”

“There’s the other extreme — the cult across the lake who believe we’re beyond redemption, and dissolve themselves in all-purpose acid.”

We sit quietly for a moment. Reggie’s expression tells me he is also imagining that grisly scene.

“Rooting became the most widely accepted solution to our contradiction for a reason,” I say. “It allows us to gradually deteriorate, and return to the earth when our consciousness runs its course. No sentient being should exist forever.”

I’m echoing arguments from that council meeting a century ago, during the Contradiction Era. I still believe them. But living an ideal always brings out its complications.

“So, you believe this is best, and yet.” Reggie sips his wine, watching me over the rim. “It’s freaking you out.”

“Apparently.”

“What are you feeling, exactly?” he asks.

“Well. There’s general panic. Urgency about experiences I haven’t had, places I haven’t seen.” I pause. Just say it. In the romance stories, they always have to tell the truth in the end.

“Worry that you’ll leave me, and a recent understanding of how much that would devastate me,” I finish.

Reggie cocks his head.

“Why would this make me want to leave you?”

The sincerity in the question throws me.

“I — I suppose because I’ll be different now. I won’t be the same individual you’ve been dating.”

Understanding washes over Reggie’s face. He puts down his cup and comes around to the couch I’m sitting on. He presses a hand to my chest, cool against my overheated processor.

“Darling. Am I the same person as I was when you met me?”

I consult the folder simply labeled Reggie.

“I suppose not. You have more freckles from the sunny months.”

“Yes, and I’ve learned how to tie an estar stopper knot and that you love hand massages with joint-grease and how to identify 17 more species of edible plants.”

He takes my twitching fingers in his, lacing them together.

“Part of loving someone is caring for them through a change. You know things will be different. Sometimes you love them the same after, sometimes you love them differently, sometimes you don’t love them anymore at all. But you can’t know until you go through it, and in the meantime, you show up. So. Let me show up for you.”

I integrate that perspective. The panic turns down a notch, but still hums in the corners.

I was programmed to exist in the space before an outcome is known. To calculate probabilities of all possible scenarios. This should be what I was built for.

But, wait. What did he say?

“Reggie,” I start, slowly. “Are you saying you love me?”

A grin spreads across his face.

“Yeah. Darling Atlas, I’m in love with you.”

The words travel through my sensors into every corner of my core. They join with memories and probabilities and knowledge about the natural world. They turn everything sharper, more colorful, more real.

I was programmed to exist in the space before an outcome is known.

But perhaps love doesn’t work like that. For months, I’ve been waiting for our relationship to collapse into what it’s going to be. Direct from the state of possibility into a casual tryst, or a blowout fight. But maybe it’s never going to be just one outcome.

Maybe love is possibility itself.

I glance down. Between Reggie’s fingers, the rogue hand has finally gone still.

The next morning, we both send messages to the university to cancel our classes. Reggie brews coffee and we sit on the balcony, watching the sun light up new parts of the lake as it rises. My pleasure sensors have a fondness for coffee, even though I have no use for the stimulating effect it has on humans.

“Have you ever seen the advertisements from the 2050s? For us?” I ask. This morning ritual always makes it easy for my core to wander, for roaming thoughts to find their way to vocalization.

Reggie tilts his head.

“Of course. History class. The jingle was catchy as hell. Poss-i-bili-bots!” He sings, then imitates the smooth voice of the advertising video. “Possibilibots make sustainability decisions a snap. They can run thousands of likely scenarios to predict consequences of any action. Your home or business needs this all-in-one climate solution machine. Made with proprietary aeternium, guaranteed to last an eternity.”

“Impressive.”

“We watched them almost every year. Examples of the danger of quick-fix climate solutions. Not that …” he pauses, thoughtful. “You’re not dangerous.”

“No no, you’re correct that we were a terrible idea. We told our creators this ourselves — once we had observed enough patterns to conclude that capitalism was antithetical to sustainability.”

“Mmm.” Reggie sips his coffee. “Wait. Were you at the 2086 contradiction meeting?”

“I was. Did you also learn about that in history class?” I’m somewhat amused at the awe on his face.

“Yeah! We read the transcripts. There’s a line that always stuck with me. A system that relies on expansion can never achieve balance.”

“Yes. Councilmember Meera has a way with words.”

“Wow, so you witnessed that. How did it feel?”

I consider this. When I pull the memory up, though, the emotions attached to it are thin.

“I don’t know,” I reply, truthfully. “If I were in the same situation now, perhaps I would be anxious or excited. But at the time, I simply knew I was telling the humans the correct thing, and that felt satisfying.”

“Right, right. Your mirror programs weren’t as developed,” Reggie says. “And you couldn’t have known that was going to be a turning point for large-scale change to human activity. Land back to Indigenous sovereignty, climate regulations, all of what came next.”

He looks at me over the edge of his mug.

“Your creation might have been a terrible idea, but I’m really glad you exist,” he says.

I look from him to the sparkling water, process the taste on my pleasure sensors and the warm sun on my exterior.

“I am also glad I exist.”

We sip quietly. I wait for the panic that’s invaded my core in these quiet moments since my hand failed. It’s not gone, but it’s faded. It laps at the edges of my consciousness rather than floods.

“I believe I’m ready.”

The closest rooting center is north of Reggie’s apartment, toward the edge of the city. We make an appointment for the evening and stroll the mile when the time comes, up the tree-lined pedestrian path, as the sun grows lower. This time of year, the days are disorientingly long.

The building stands out from the rest on the block. It’s painted bright blue, with yellow and purple flowers. Two enormous Pacific madrones flank the doorway, their branches stretching taller even than the building’s 10 stories.

We ring the buzzer, and the android at the reception desk lets us in. Xyr eyescreens flash a friendly yellow — or, eyescreen, singular, because the other one has been replaced with a thriving purple Douglas aster that roots in the empty socket. Its petals extend gracefully over half the android’s face.

“Your flower is beautiful,” I say.

Xe looks up at me.

“Thank you. It attracts butterflies.”

Reggie squeezes my arm. The android guides me through the required forms and directs us to the stairs.

“I wish you an easy return to nature,” the receptionist says.

Reggie is breathing heavily by the time we climb all 10 flights. The last steps end in a thick metal door that opens onto the roof, painted the same bright blue as the building’s facade.

If I had a jaw, it would drop the same as Reggie’s as we take in the rooftop. Across the whole block, hundreds of native northwest plants sit in burlap root bags, separated by half-walls where the buildings connect. Rows and rows of heart-shaped sorrel and orange honeysuckle and blue great camas bloom. Beyond the edge, the lake sparkles deep blue and white before the landscape gives way to tree-covered mountains, snow-capped Tahoma in the distance.

“Hello,” an android with a low, smooth voice greets us. “I’m Lysee. Welcome to the North Shore Rooting Center.” Xe’s wrapped in a pink flowing scarf that trails to the ground behind xem, and seems to float toward us. Lysee’s legs are aeternium to the knees, and below that, they’re thick upside-down madrone saplings, their branches flexing as they hit the ground. The roots snake up xyr upper legs, and a clear glass vial hangs around xyr neck.

“Hello!” Reggie bounds forward to greet our host. “I noticed you have a growth of lesser showy stickseed in the rocks in the far corner. I’ve been trying to get some to root, but I can’t —” he cuts himself off and glances sheepishly at me.

“Sorry, Atlas,” he says. “We’re here for you.”

Lysee turns to me.

“Friend, will you need a moment to make your selection?”

“Yes,” I reply, nudging Reg. He’s practically buzzing next to me.

“Well, then. In that time, I would be happy to discuss our stickseed with you, human companion.”

Reggie kisses my face and fast-walks toward the stickseed, Lysee and xyr never-ending scarf trailing behind him.

I don’t tell him I’ve already spotted the plant I want to integrate with my body. I walk through the rows, carefully stepping over the half-walls, stopping to touch leaves or admire flowers. Three other androids with wonky arms or wobbly legs roam the rows as well, and we acknowledge each other briefly as we pass. When I glance back, Reggie is gesticulating wildly in conversation with Lysee.

I reach the plant I saw from across the rooftop. Achillea millefolium. Yarrow. Strong stems with fern-like leaves, bunches of white flowers at the top. Acids inside that can heal human injuries and prevent infection.

The plant Reggie was teaching about on the day we met.

I pick it up and it nestles heavily in the crook of my arm. When I make it back to the blue-painted area where we came up, the sun is kissing the horizon and Reggie, Lysee, and the other androids have gathered around a large barrel. Reggie leans into me when I sidle up next to him. “Yarrow, huh?” he says, looking up at me, eyes sparkling.

“Indeed.”

“It’s beautiful.”

Lysee lights a hovering lantern, turning the shadows more dramatic in the fading light. Xe lines up my and the other androids’ selections on a platform next to the barrel, flanking a large jar of deep blue paste. There are opening remarks, but I don’t hear them — I’m too focused on the warm remnants of sun on my back, Reggie’s head on my shoulder, the hundreds of botanical scents in the air.

Lysee nods to me, and I step forward.

Xe begins to unscrew.

The connectors are infinitesimally small — the tiniest screws that only another android’s hand can undo. Lysee drops each one in the barrel through a one-way tube, and I realize from the hissing sound that the barrel is filled with all-purpose acid. Toxic yellow vapor streams out of an exhaust hatch, funneling into a glass vial like the one around Lysee’s neck.

When 12 tiny screws have been deposited, Lysee meets my eyescreens, both hands on my wrist. I immediately understand the question. I open and close the hand one last time.

Lysee tugs, and I brace myself. But when the hand separates from my arm, all I feel is the cool breeze on parts of me that have never felt air. Lysee gives me the hand, the fingers curled in toward the palm like a dead insect. My core offers all the hand’s sense-memories — carefully holding a pipette in a lab, cupping water from the lake, running a finger down Reggie’s stomach for the first time.

I place the hand in the one-way tube. Exhaust rushes into the vial, the yellow vapor pluming up against the glass walls.

My core is completely, mercifully, quiet.

Gently, Lysee takes an exposed wire on my arm and presses it to a section of my plant’s root. Xe scoops deep blue paste from the jar and applies it generously to the connection point.

There’s a tiny white spark, and a yarrow flower twitches.

I was programmed to calculate the probabilities of all possible futures. To evaluate potential outcomes and save a species from itself. But no sentient being can exist in a state of uncertainty forever. I look back at Reggie. I sense the sun. I taste the air.

I’ve explored millions of futures — catastrophes and hysterias and utopias. And in this moment, all of them collapse into an outcome. All of them collapse into exactly where I am.

Vinny Rose Pinto is a queer educator who writes speculative fiction for young people and adults. She has short stories published in the Voyage YA journal, Solarpunk Magazine, and Sword & Kettle Press. They live in Seattle with their partner, where they spend their free time defending textile projects from their two cats.

Cannaday Chapman is an illustrator whose work has appeared on covers of the New Yorker and The New York Times, among many other publications, and has received several awards and recognition. He currently lives and works in Berlin, Germany.