Imagine 2200, Grist’s climate fiction initiative, celebrates stories that invite us to imagine the future we want — futures in which climate solutions flourish and we all thrive. Discover the 2025 contest winners. Or sign up for email updates to get new stories in your inbox.

The rainmaker drone soars over the field to a chorus of curses and shouts from the clump of men in ancient, tattered Buffalo Bills jerseys. Number Twelve on the offense owns the turtle we’re here to see, and he won’t talk to us until the game is done. He might be playing halfback. I don’t know. From wet seats on rusty bleachers we watch the men line up to bash each other again and again in the muddy earth until the field is reduced to Agincourt.

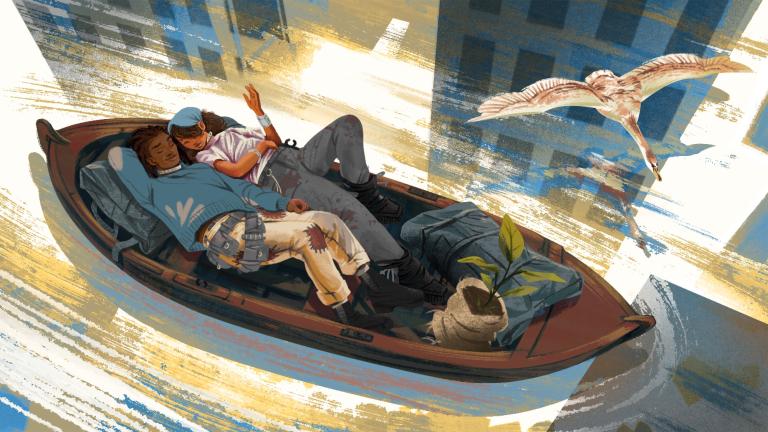

Echo’s history lectures must be wearing off on me. My joints ache, but at least my brother’s enjoying the rain, heedless of the dirty looks from the few other spectators, those who don’t differentiate between rainmakers and quadcopters, those who look at any drone with suspicion. He’s humming a tune of little electronic warbles with his battery panels unfolded, feeding off of the kinetic energy of the droplets, and I always think this charging position makes his fragile metal chassis look like a monarch butterfly. If they knew how young he was, if they knew how little any of this world was his fault, they wouldn’t look at him like that.

“Buffalo,” Echo intones, voice warped slightly by the tinny speakers, “from the Latin bubalus, itself from the Greek boubalos, a type of ox. The team is named after a city in turn named after a nearby creek, which, erroneously, was dubbed ‘Buffalo’ after the American bison, now extinct, genetic model regrettably not captured in my database.”

“Real interesting,” I murmur.

“It’s history,” he says. “Continuity. Anyone can appreciate that.”

“I’d appreciate it more if they could just give us the turtle.”

Echo just beeps in response. Blanding’s turtle, it’s called; the thing we’re after. The next on our extinction list, the thing I’ve traveled 1,300 miles to find, the thing that must’ve been named long enough ago that a species could be dedicated to a person all without ever knowing it.

Number Twelve gets the ball, forces his way through a pile of men, goes down. Repeats the process. Everyone looks miserable. Some people don’t know when to give something up.

Somewhere far above, the rainmaker makes rain. Once weekly it synthesizes silver iodide from trace elements in the stratosphere. By the time it dives back to a more reasonable altitude, the necessary compounds have been added and the mixture is ready for deployment across upstate New York. Not that there’s anything left to be upstate from. It’s a parody of nature, a whale gorging on krill in reverse. The drone flies through cumulonimbus clouds and vomits infinitesimal particles about which the air molecules swirl like giddy cultists. A simulacrum of sheet lightning erupts from the rainmaker, charging the molecules, inducing the rainfall. And the land beneath it continues to drown.

Someone long ago was sure this would work, that the follies of last century could be solved with broad, sweeping gestures. Society wouldn’t need to change on a large scale; this one project, this one policy, this one billionaire would fix everything. How many times has that wheel turned?

The thing is automated. Unceasing. No one is in control, and home, wherever it is, has long since stopped signaling.

Assuming a steady usage rate, the rainmaker will run out of cloud-seeding compounds in 317 years.

Number Twelve won’t show us the turtle, even though his side won.

“Not here,” he says. We’re under the tent at the edge of the field with a few dozen others — players and their families. Water runs in thick, splashing sheets around the sloped rim, pummels the canvas roof. There’s no way to stay dry here, not really; no way to avoid the sight and sound and feeling of this omnipresent rain.

Twelve nods to one of the other team’s players, a short man with a ponytail now trudging to the locker room. “Jackson isn’t happy about losing. Real hothead. You know how people up here feel about drones. Probably think your buddy there is a baby rainmaker.”

“That’s not how it works,” I say, and all of a sudden I’m on edge. I don’t like it when people change up the plan on me. Echo flies out into the downpour, losing himself in it; I wish he’d stay closer to me. But we have a deal: He won’t get himself into trouble without a good reason, and I won’t stop him from going where he wants to go.

“I’m trying to help you,” Twelve says. “Stay and get the shit kicked out of you if you want. Otherwise, meet me in the parking lot in five minutes.”

Five minutes later, Echo flies back to me, and we’re taking off up the road as some of the other team’s players find their car batteries have died. If Echo is a little overexcited, Twelve doesn’t seem to notice.

It turns out that Twelve’s turtle isn’t endangered.

“You should still take care of it,” Echo says. His cord is plugged into the truck’s cig outlet as we cruise down a pockmarked highway; not the most efficient charging method, but that’s the price of adaptability. The truck’s an older model combustion engine, pistons powered by 60 little acts of violence a second, fractional erosions of our biosphere. Should I even bother feeling contempt? The locals here have given up. Nothing they do can stop the rain, so why do anything? Why not just wallow in the mud with the sad little trappings of how things used to be?

We’re headed north, The terrarium is in the passenger seat, with Echo right next to it, cameras peering in through the glass. For my money, it looks enough like an endangered turtle.

“Only caught it in the first place because I thought it was rare,” Kevin says. I have to give him partial credit. Most people just ignore Echo, or assume he’s an LLM or some other kind of bullshit AI. It’s rare for him to be able to have a real conversation with another person.

“It’s a living creature. Diamondback terrapins are still rare, just not as endangered as Blanding’s turtle. Do you mind if I scan it?”

“Go ahead. But I thought it was a turtle.”

“Well, it is one,” Echo says as he prepares to collect the sample. He’s so much more patient than me, so much more willing to teach. “A type of one. ‘Terrapin’ is just an old Algonquian word meaning ‘edible turtle.’”

“You can eat it?”

“Give me a second, here,” Echo says, and extends the scanner. It’s a noninvasive procedure that he designed himself, refined over years. My brother, at 19, is the world’s premier expert on the animals that he scans, 46 endangered species and counting that everyone else has effectively abandoned. The least we can do is remember them.

I help him where necessary, hold the turtle still as the truck jerks and shudders over potholes and cracked asphalt.

“You might find this interesting,” Echo says to Twelve, still working. “Did you know they were playing football here two centuries ago? A little farther back it was soccer, brought over from Europe. Lacrosse before that, from the French for ‘hooked stick,’ after the game they saw Indigenous communities playing.”

He pauses before speaking again. “The Mohawk called it begadwe. The little brother of war.”

Then his rotors whir, lights blink, and he goes silent.

Somewhere down in Florida, 1,300 miles away, my brother’s body is in pain.

I got a little bit of what he has, or maybe he got a lot of what I have. The groundwater wasn’t so bad when I was born, or maybe our parents’ bodies weren’t so full of plastics. I just have issues with my tendons, and my joints hurt when it rains. He has it worse: breathing issues, neurological problems, autoimmune system compromised. It’s a hard life, and, until I salvaged the drone to be his eyes and ears, a lonely one. He was born into an unforgiving place, and even as much as our community’s done to accommodate him, there’s no such thing as a perfect solution.

And then we started traveling, me on foot, sometimes hitchhiking, him in his drone chassis, controlled by a frail body hundreds of miles away and still vulnerable, facing temporary shutdowns and jammers and assholes with baseball bats who look at him and see a mailbox.

It’s a few minutes before Twelve notices.

“What’s wrong with your drone?” he says.

“He’s fine. Don’t worry about it. Just keep driving.” I feel sick, performing the usual calculus. Trying to remember if Echo mentioned anything about feeling worse today, if I noticed any oddities in his behavior. Anything that would suggest the issue is on his end, biological, not technological. His sickness isn’t terminal, or isn’t supposed to be, but things can change, and I’m so far away. Somewhere in my mind a countdown is ticking. It could be the car battery trick catching up with him, or just the influx of genetic information triggering a reboot. Neither of these options assuage my anxiety.

Talking does, though, and so when Twelve asks me why we even wanted the turtle, I tell him. I tell him that we’re trying to build a database of species in danger of dying off, I tell him that my brother is the real mastermind behind this and I’m a glorified pack animal. That I don’t even know much about any of these species, that I’m not so much of a true believer in the mission as just somebody trying to keep his brother safe.

What I don’t tell Twelve is that we have rainmakers back home; that in our community the rain is a blessing, that the same thing dooming this place is our salvation. What I don’t tell him is that when the ocean currents collapsed and normal weather became uncertain, our grandparents did whatever they could, threw solutions at the wall until something stuck. What I don’t tell him is that whatever tech-forward billionaire trying to regulate the rain down in Westchester or wherever probably doesn’t give a shit about the people up here, if he’s even still alive, probably doesn’t mind if the whole Rust Belt drowns.

He tells me about football, in return, which tracks with most of the conversations I’ve had up here.

“It’s the same as your brother,” he says. “We’re keeping the spirit of the country going.” The rain runs off the windshield in blurry, messy lines.

“Is that so?”

“You’re recording the animals before they die out. We’re recording the culture.” He slaps the dashboard of his truck like the flank of a faithful mule.

“We already have recordings of football games.”

“Footage isn’t the same. Like asking someone to describe a concert.”

“That’s true of the animals, too,” I say, a little heated. Why do I care what this guy thinks? “But we’re doing the best we can. It’s the least we can do to remember them.”

“And that’s great for you, and the animals. But we have the capability to keep the old culture going, so we’re going to keep it going, even if it means getting rained on for all four quarters every Sunday. If we don’t, no one’ll remember anything. Then this country might as well be extinct.”

The conversation shifts lanes; Twelve veers into obscure football minutiae and the recounting of particularly memorable games. I’m not really listening as I watch Echo, waiting for any sign of a reboot, anything, and thinking about the last thing he said.

Somewhere in the backseat, I drift off. All the travel catches up to me, just for a minute. Twelve is still talking up front and I hear, or imagine that I hear, the beeps that signify the beginning of Echo’s reboot process. In that half-dreaming moment I see the world as my brother must: clouded, beautiful and pulsing; rich with water and power and fragments of history falling all around like raindrops. Down below are the football players; time runs backward as the nature of the game shifts, as the rain is sucked back up into the clouds, as the game becomes soccer and then lacrosse, begadwe, war without war. I wonder if Twelve cares, if he ever asks himself why only certain aspects of the past are preserved, or if he knows how much of the culture has been sanded away and forgotten, or if he ever questions why the spirit of the country should only go back so far.

In the dream the rainmaker passes above, the sky-whale, object of so much ire, and I see that it isn’t drowning these people but fixing them in stasis, that it isn’t seeding the clouds but whispering to them, reminding them of a time before, a false frozen moment.

Twelve lets us out of the truck on the shore of the ocean. But that can’t be right, there’s no way I slept that long. I blink the sleep out of my eyes and look again: it’s a lake that’s bigger than any I’ve ever seen.

“Lake Ontario,” he says proudly. “Still fresh water, for now.”

He doesn’t want to get out of the truck, even though he promised us this would be a safe place to drop us off. So I thank him for the turtle scan, and Echo, who’s finally coming back online, beeps in muddled appreciation.

As we walk down the shore, Echo comes more and more into himself, leaving behind his Florida body and regaining control over the drone. He doesn’t want to talk about what happened, so we travel in silence. He’s peering off into the endless foggy distance over the lake.

“Can you see it?” he asks.

“Your cameras are better than my eyes, Echo.”

“It’s out over the lake. The rainmaker. And it’s been trailing silver iodide for miles.”

“Doesn’t sound good.”

“This place isn’t going to survive much longer,” he says, turning toward me. My eyes are reflected in his lenses. “That rainmaker’s done so much damage already.”

“We could just leave. Hitch back south, go home. Or just skip a little ways down the list. Head for those last bumblebees on the West Coast.”

My brother has nothing to say. He just stares at the rainmaker above the lake.

The old man on the shoreline looks up as we approach, thin pink slash of his mouth twisting. He has a little camp set up under a tarp where a tiny creek meets the lake.

“Let me guess. My brother dropped you off here. Told you I’d take you somewhere safe.”

“After his football game.”

The man’s eyes twinkle. “They’re all so concerned with those games.”

“You speak like you aren’t from around here.”

“Oh, I am. Born and raised. I’m just not as bought in as some of them. You boys aren’t, though. You’re from one of those Florida communes, aren’t you? Eco-conscious folks and all.”

“Might be,” I say. I don’t like where this is going.

He gestures toward the empty chair next to him, a mobile power brick next to that. I raise an eyebrow, Echo plugs in.

“How’d you know we were coming?”

“All over the radio,” he says, smiling. “Guess somebody at the game didn’t like you. Look out for a man with a drone, public enemy and all. Something about their batteries being drained, too.”

Shit.

I turn to my brother without taking my eyes off the man. “We need to get out of here. Head back home. This place is poison.”

He makes a plaintive beep. “We still have a few species on the list that should be around here. And the people, they’re drowning. Grasping for something to keep above the waves.”

The old man nods. “They aren’t blameless. What they’re reaching for doesn’t exist anymore, maybe it never should have. But it’s that rainmaker killing us, turning everything sour. Making them think all we can do is stay where we are or go back.”

“Rainmaker,” Echo intones. “Compound word. Once used to refer to someone who brings money or fortune to a company. A problem-solver. Before that, a title for a shaman or other figure, such as in the Osage tribe, involved in rain dancing, a method of calling for rain.”

“Echo,” I say, “It’s time to go. We can’t do any good here.”

“I don’t think that’s true,” he says. He’s looking out over the lake again, seeing something that I can’t. The long view has always been his strength. So why am I so anxious?

He disconnects the scanner from his chassis, proffers it to me. “Maybe not with this. Or maybe just not with this right now. Maybe there’s a time for immediate solutions, too. Maybe you can keep doing the list without me, or you can come back home someday and find me a new drone to use, or —”

I stand up, suddenly, and I almost lunge for him, but — our deal.

I won’t stop him from going where he wants to go, as long as there’s a good reason. He flies up out of my reach.

“They’re looking for a man and a drone. If I’m gone, you have a better chance of getting away. And if the rainmaker goes down, maybe they won’t be looking for you anyways.”

“Echo, it could be years before I get back to you.”

“Then I’ll miss you until then.”

I’m out of words, choking on them, knowing that I can’t stop him, I shouldn’t stop him, I want to stop him.

He’s gone. The old man stands next to me, out from under the tarp, in silent vigil.

Somewhere far above, the rainmaker makes rain. My brother intercepts it, fragile and tiny as a butterfly against the cutting bulk of the rainmaker’s sharklike silhouette. When it reaches its destination, he’s there, waiting, his charging cable held aloft like a lance, like a gleaming sword. But how could a swordfish kill a shark?

As it flies through the cumulonimbus clouds he strikes, diving for the open belly of the thing, hooking onto it like a barnacle and draining. Too much, taking too much at once to avoid feedback, but it’s the only way. Another reversal: a single krill gorging on a whale.

He’s sure that it will work, that the follies of last century can still, sometimes, be solved with decisive, singular gestures. And he may be right.

His drone is automated. Unceasing. Full of stolen power as the rainmaker lists and nosedives. No one is in control, and home is so far away.

I have thirty four species left on the list.

The first animal we ever scanned was a manatee back home. Echo didn’t have the drone controls down yet, and the waterproofing was still a little touchy, so I had to do it. The thing floated in the water like a big trusting balloon, rubbing against me with its whiskers and drifting along as though heedless of all the pain in the world. I could see why they were on their way out as a species.

We were completely submerged, the manatee and I, all but the tube of my snorkel. From above I could hear the muffled voice of my brother telling me the Carib word from which manatee is derived. Looking up, I could see the drone shifting ceaselessly through the lapping ripples: my brother, a drone, my brother again, instructing me with a smile in his voice as he guided me through the process. As though above the surface was a world in which rightness and goodness were tangible qualities that expressed themselves in the little sounds, the beeps, the laughter.

Parker M. O’Neill lives and writes in — you guessed it — upstate New York. He is a recent winner of the Elegant Literature Award for New Writers, and his fiction appears in Apex Magazine, Flame Tree Press, and Crepuscular Magazine. Find his socials at https://linktr.ee/parkermoneill.

Cannaday Chapman is an illustrator whose work has appeared on covers of The New Yorker and The New York Times, among many other publications, and has received several awards and recognition. He currently lives and works in Berlin, Germany.