Imagine 2200, Grist’s climate fiction contest, celebrates stories that offer vivid, hope-filled, diverse visions of climate progress. Discover all the 2024 winners. Or sign up for email updates to get new stories in your inbox.

Lærke’s first word was wing.

She lay cradled between the moss and her mama, watching the branches cut the sky in precise patterns. Her poor ma Suzume had fallen asleep after chasing the child around the farm, trying to keep Lærke’s tongue out of the beehive. The city’s colorful turbine balloons hovered high in the atmosphere, silently harvesting wind — and look there, the giggle of a single cumulonimbus in an otherwise blue sky.

Little Lærke’s developing mind observed the canopy overhead, babbling her wordless song above the comforting thunder of her mother’s snores. Then the word took shape on her lips and flew. Wing. Out into the world.

Auntie Cade looked up from the sacred text her needle had been working, the folds of fabric bunched in her lap. She’d been humming the ballad as she stitched those lessons of the living land, quietly harmonizing with the baby’s joyful yoller, but fell silent when she heard the word. The child’s first!

She followed Lærke’s gaze up to the sky, expecting to identify which dot in the kaleidoscope of community kites had caught the child’s attention, then eased herself down beside the babe to see from her perspective. Which of those turbine balloons or spinning kites and whipping dragontails in the skies had teased the first word from the baby’s lips …?

Maybe that one? One of the neighbor’s blimp turbine designs had dual blades that flashed like hummingbird wings — not the most efficient design, but since when has creativity been overly concerned with efficiency? It was certainly eye-catching.

Instead, as Auntie Cade nestled back close to the baby, cheek-to-cheek, Lærke showed her auntie a butterfly wing swirling dust motes ignited by the sunlight.

“That’s right, wing,” Auntie Cade affirmed, and pulled The Field Guide blanket up over the three of them. They snuggled in under the weight of wisdoms passed from auntie to auntie — woven, crafted, compiled — while Lærke and her auntie watched the butterfly dance in the golden pollen.

We always say a child’s first word is a gift.

And look at that.

…

You’re … hm. You’re not watching the butterfly. Look …

The blue of the butterfly wing is not a pigment, the color is formed by a delicate structure that refracts light itself, much like the blue of the sky. No real surprise that the beauty of chaos has been represented in the motion of—

You seem distracted. What are you looking for? Me? You’re wondering who this person is, telling you to look here and there. You want to know who’s telling the story? Fine.

I am a storyteller. The storyteller. This story’s teller.

There’s no use scanning the edges of the scene trying to find me. I’m not perched on a boulder beside these three as they’re experiencing this intimate, poignant moment on this lovely day. You think I’m up in a tree looking down on the scene? With these knees? Please.

I’m omniscient, but I’m not a creeper.

You can most often find me in the Tangle, the place in the city where paths converge. I don’t have to be present at every moment to know what’s going on. People tell me things. I have a trustworthy face.

Step closer. Let me get a good look at you. Knowing who we’re telling the story to is part of the craft: “The storyteller assesses their audience.” Watches the people as they mingle in the Tangle. Notes the dress of the passerby, their manner. A storyteller wouldn’t tell the same story to the lonely child seeking solace in the storyteller’s lap as they would to the bawdy crowd on their way to a fertility show.

Or at least, I wouldn’t tell it in the same way.

Any decent storyteller has this skill, it’s the same observations about character that we weave into our tales. Is the listener in a rush? Are they looking for escape? Do they need a single golden spiderweb thread to sew together something frayed inside?

Some storytellers tailor their tales to what their listeners want. My training taught me to look for the story the listener didn’t know they needed.

And you. A reader from the tail end of the blip era, what story do you need from me? Am I even able to tell you a story you will understand? You’re most likely steeped in the narrative techniques of the settler literatures of the time. Tricky … but difficult things are not impossible, and I wouldn’t be a storyteller if I didn’t like a challenge. Besides, you’re in luck. Though the story trends popular in the 21st century have long gone out of style, I just so happen to enjoy experimenting with this outdated form. I’m afraid that most current storytellers have found that the simplistic structures you’re familiar with often fail to capture our children’s imaginations so they’ve largely been left for archival scholars to catalog as a hobby. I have a friend who does this. Winslowe. He finds it relaxing. Hero goes on a journey or A stranger comes to town. His husband Jibril finds it tedious, but I admire people who are passionate about their passions! Whatever makes him happy, we agree.

Let me tell you about their son, Ben.

Aunties aren’t supposed to have favorites, and they don’t. Hierarchical thinking isn’t actually natural to human cognition, and there isn’t any scarcity of resources to compete over. Especially in regards to a person’s capacity for love.

If you ask Auntie Cade though, and I have (storytellers ask the most impertinent questions, get used to it), she was uniquely grateful for Ben. We all were, but part of that was due to Auntie Cade’s … interpretations … as she decoded the intricacies of his language. It turned out to not be a private language, like maybe his parents and peers, cousins, siblings, storytellers, neighbors, and neithers assumed. Ben was in communication with all the unheard and mostly unseen, outside the spectrum of general human understanding.

I don’t want to make this telling of a slight, autistic Black boy to sound unnecessarily mystical or mythical. He’s a person. But sometimes one’s love for a person embellishes their qualities — they swell with our regard, inflating like a generator-blimp before we hoist them high. Once a storyteller gets their hands on a person, they make the character appear larger-than-life. Is this the mark of fine craftsmanship or a rookie mistake? (You can tell me, it won’t hurt my feelings.) Why shouldn’t the loving renderings of an artist’s brush caress a child, stroke his cheek, and tickle his armpits?

Ben would hate it, so that’s one reason not to. And the only reason we need.

Of all the children she’d taught and inspired, nurtured and guided and delighted in, Auntie Cade recognized that she’d learned the most from Ben. She told us that Ben showed her things; he’d shown them to all of us, but sometimes it required an auntie’s attention to understand a child.

Our culture puts a lot of weight on a baby’s first word. (See above.) Not so much what the baby says, mostly that the baby says. That they’ve arrived at a phase of language acquisition which marks their inclusion in the community conversation.

Feral cats don’t meow. Or so the story goes.

We talk about everything. People do. The ASL sign for a hearing person is the same as the sign for TALKING. We’re always talking. Especially the people I know. It varies from neighborhood to neighborhood, culture to culture. But for the most part, we’ve evolved, especially since your time — those blip generations when decisions were made by might, hierarchical decree, or just not made at all — we’ve learned how to talk things out.

Feral cats don’t meow. Or so the story goes.

When there is a problem, we gather. And talk. Not to be heard, but to discuss. We approach the discussion acknowledging that there is a problem, and that the solution is not yet known, because if any one person knew how to solve that problem, it wouldn’t be an issue, now, would it? If it were a problem easily solved, we would’ve made quick work of ensuring it wasn’t a problem. We would instead be off braiding bread or rinsing the vegetable inks from the pages of a library book and searching the catalog for a new one to print — living our lives. No, if we’re there in that room, in that clearing, filling that field, meeting in a sports arena — then we have a problem so tricky that it needs everyone’s input. Children as young as six years old have contributed to civic matters. Do voices get raised? Sure. Do men burst into tears? Quite often. Do passions drown out reasoned accounts? Eh, not as often as you fear. Our children learn to listen at a young age and become adept in the skill as adults. I see it straining your imagination, stranger-comes-to-town, that the opinions of each individual in a mob could be worthy of respect. Do not feel bad about your disability, we see it as a failure of education … one of the many things lost in the blip generations, along with the 83 percent loss of biodiversity in the sixth mass extinction event you are currently living through.

But we were talking about Ben. How could a culture of loudmouths appreciate a quiet kid? Who grew to be a silent adult?

Because, unlike the “domesticated” cat, most of the wild creatures we share a planet with didn’t go out of their way to try and learn our language. To vocalize their need, to pitch their voices like a baby’s cry, to trigger a physiological response that requires immediate attention from people who hear it. Feral cats are silent because they don’t want to attract attention to themselves or communicate with people. They want to be left the hell alone.

Animals have rich languages of scents and gestures and vocalization patterns. Able to communicate between themselves and with each other, and very few of us have gone out of our way to understand the linguistic complexities of our fellows. Not with the same determination of the cats, at least. “But could those things really be considered language?” I hear one of you say. Your white sciences change the definitions and shift the goal posts every time a community of creatures approximates those arbitrary markers for intelligence, sentience, life. Every time. To ensure that only human people stand in the circle — and terrifyingly often, it’s only the people with similar qualities of those enforcing the definitions who are allowed in. Personally, I tend to wonder if that culture built on exclusion, exhausting itself to enforce artificial borders (or otherwise centering a single person’s narrative thread, consequently relegating the rest to less important supporting characters and background greenery) may have led to the worldview that brought your generation so close to ending the ever-generating world.

So yes, I say language.

Listen to birdsong as you walk through a place with birds … I was going to say “the woods” but that might be difficult for you to find, presently. Things were dire at the tail end of the blip era, as I understand it, you were so very successful in excluding everything unlike your kind … Anyway, walk among birds. Listen to their trilling call-and-response. You can be sure that they are talking, and I guarantee they are talking about you. You are big news in the woods. They are not quite sure what to make of you. Are you a predator? What have you done to assure the birds that you are not a threat? It’s easy enough to show them. Their birdsong is asking. They are waiting for a reply.

Ben’s first “word” was a reply. Our culture has a parallel language system of gestures; yours might, too. A thumbs-up, a corny salute. A peace sign, a fuck you. Our neighborhood has a gesture of gratitude — two fingers pressed to one’s own lips. Thank you. And one to express a wordless need — hands cupped into an empty bowl. You would probably try to find the words for this feeling … general malaise, vague disappointment, unfulfilled desire, a soft sense of regret. You know the feeling … it’s just a nameless funk. Instead of trying to locate the feeling, to understand it — or jerkily act out in desperation to feel anything else — our people tend to just signal the inner turmoil we’re experiencing by cupping our hands into an empty bowl. Close to the body if we want to be left alone with the feeling, extended out from the body if we need someone to pull us out of it. It’s useful. Easy to communicate. Both for one’s self and to others. The prevalence of tragic instances of ill-advised bang-cutting in our society has diminished, at least.

When Ben was maybe 3 — long past the age most expect to welcome their children through the rites of their first word — Auntie Cade was walking alongside Ben during their daily route through the Tangle. She would follow where he led, always close enough should he need her, but never insisting on holding his hand in the crowded public space. He didn’t like for his hand to be held and it’s easy enough to allow small children their autonomy generally, Ben in particular. His morning routine was sacred to him and he was never at risk of running off.

On this day, Auntie Cade witnessed Ben making his quiet wander to his favorite places. He watched the glassblower turn sand into exquisite shapes — mesmerized by the lava blobs birthed in fire and brought to life with breath. The glassblower was a small man with thinning hair and a quiet voice. He did his work, seemingly indifferent to Ben’s constant presence — a feat, since people are otherwise hyper-aware of a 3-year-old in the vicinity of molten stoves and display shelves of delicate glassworks. But the glassblower had come to an agreement with Ben, an arrangement. Each day, the glassmaker dropped a single glass marble into a large, wide bowl just as Ben was ready to leave … in gratitude for the child’s attention and as thanks for him not touching all his stuff or breaking anything.

Ben listened to the smooth, nearly frictionless vibrations as the marble rolled in a path up the sides of the bowl and around. Ben’s eyes followed the lazy arcs and parabolas, and when it tinkled to a stop in the center, Ben reached in with his small fingers and picked it up. He examined the color and the finish of the marble, weighed it in his hand, and, satisfied after his appraisal, placed the marble he’d carried around all the previous day onto the rim of the bowl and let it circle to rest at the center. Then he left the workshop with the new marble nestled in his palm.

I’d asked the glassblower about this ritual, and about the day it changed. I had to tease the story out of him, slowly, like the expanding bubble of glass. He told me it started as a simple token, the kind he often gave children in gratitude for not touching any of the fragile wares. The first one was rather large — Ben was still small and there were no assurances that he wouldn’t put it in his mouth. (Auntie Cade assures me that he never did, which she found odd, since he put everything else in his mouth at that time — except for a variety of foods she hoped he would like.) Ben carried the fistful of smooth glass cupped in his chubby hand the whole day, and when the glassmaker presented him with a new one the next day, baby Ben deposited the old one and clutched the new. That was what intrigued the glassmaker, he’d assumed Ben would collect them like other children often did. He’d meant for the baby to have both. All of them.

We don’t like to use words like exchange or trade … they’re so rooted in blip characterizations of transactional relationships that we just … find more accurate words. But Ben started this ritual, and each morning, the child plucked the new gift from the bowl, examined it, then returned the one from yesterday before accepting the new one. Until one day, Ben picked up the day’s marble, and for whichever reason, preferred to keep hold of the one he had, and let the new one slide back into the bowl.

The glassmaker was startled, curious, and after the boy left, he picked up the marble and examined it. It was of the same quality as all the other marbles. What inspired the child’s preference for the previous? “There were no imperfections,” the glassblower told me while clipping a molten blob of glass, it curled in on itself like a living larva. “But there was some quality that displeased him, or at least persuaded Ben to keep holding on to the one in his hand.” Here I had to wait some time for the glassblower to roll his rod and use gravity to temper and shape the glob that would become a kind of vase. “That’s when it started. It went from a game, to a challenge, to …” He stared thoughtfully at the fires. “An inspiration. I am so grateful to Ben. His careful regard has inspired the development of my craft to a degree that … no one else would probably notice, but I know that he notices. Propelled by the urge to please him, my craft has been elevated to art and then to an act of devotion. I’m still not sure what the boy is looking for when he makes his assessments. It’s not perfection. Perfection is easy compared to this. I just want to make something that makes him happy. Something he wants to carry around with him each day, every day.”

I’d asked the glassblower if he’d ever felt offended. Refusing a gift can be a sensitive matter. The glassblower was startled, “It never occurred to me to be offended. You know Ben. The social rules of the gift don’t apply. It’s just him and me and the day’s marble.”

Perfection is easy compared to this.

I later learned that on the day I’m taking my sweet time in telling you about, the moment that Ben joined the extended family of the living world, Ben had been holding on to the same marble for two ten-days. That marble was blue, with cloudy swirls of white and flecks of green-brown. The glassblower had presented him with 20 examples of his refined craft — some vibrantly colored and particularly large or remarkably small, since the glassblower was getting kind of desperate to create something that would win the boy’s favor — and none of them satisfied Ben’s internal matrices of color, feel, and weight that made a gift a pleasure to hold.

“I still have no idea what it was about that one that appealed to the kid,” he let his sigh shape glass. “It was even slightly misshapen, with a bit of a bulge around the equator. Not at all my best work.”

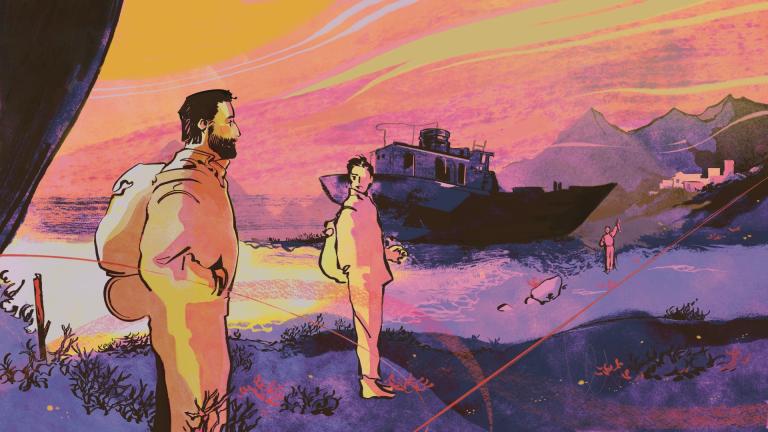

But this was the one Ben didn’t want to let go of. Come, let’s go catch up with him. You’ll soon realize why I spent a seemingly disproportionate amount of time imbuing so much meaning into a smooth chunk of glass a 3-year-old carried clutched in his grasp. There he is. He’s moved on from the glassblower’s workshop to watch the rivermen unload their shares on the Main Stream docks, with Auntie Cade shadowing alongside him.

The crew rolled barrels onto shore, tilted them upright in a row. Ben watched them pop the tops off the barrels and plunge their hands elbows-deep into the watery contents. They wrestled strands of kelp from inside and strung them, glistening, up on a line, so the sunshine glinted off the slick surfaces, highlighting the variety of each. The exquisite variations in colors and textures and shapes.

Red sea kelp, which eases digestion processes in ruminants … decreases the methane content of cow farts — and can also fry up crisp and salty like bacon. Tasty. Exotic sugar kelp harvested from Nordic shores, alongside eelgrass gleaned from local seagrass meadows. Ben silently regarded the hanging kelp strands glittering like festive garlands, their home-waters draining back into the barrels beneath, while people stopped to admire and inquire.

“Pretty big haul today,” Jibril’s voice boomed out, and he rested his big dad hand on Ben’s back. Ben flinched away from the touch. “Oh, sorry, Benevolence.” Jibril apologized and glanced at Auntie Cade.

She admonished him with a twitch of the corner of her mouth, and nodded encouragement.

Jibril knelt beside his son and lowered his voice. “I thought I’d find you by the boats. You like the boats?”

Ben didn’t answer or meet his eyes. He poked at one of the slimy air bladders bobbing on the surface in the sea barrel.

Jibril joined him in pinching and stroking the glistening seaweed, and started to make conversation with the rivermen.

“These specimens are a delight,” Jibril said. “I don’t think I’ve seen sugar kelp available for some time. Rough seas?”

“No more than usual,” a riverman shrugged as she ladled more seawater on the strung-up strands to keep them glistening and hydrated. “Hydrofoil yacht pirates are always trying to take more than their share, but these beauties came through from the kelp farms of Sør-Trøndelag.”

“They’ve come so far!” Jibril exclaimed, “Ben, this seawater is from the far seas. Incredible.”

Ben continued to poke the air bladders, obviously sharing his dad’s fascination with the seaweed, though maybe not for the same reasons.

Everyone called Winslowe “Ben’s dad” and Jibril “Ben’s big dad” (Ben, of course, didn’t refer to them at all). Jibril was, yes, a hulk of a man, but it was his outgoing personality that gave him his “big dad” stature. He and his mama Kerime kept a community tavern attached to the Archives, where he and Winslowe and Ben had a small living space above the library. “You’re off-loading?” Jibril made note of the number of barrels.

“Most of it. We talked to Lis, who said salvage crew approved a rebuild of the generator serving East Bear cluster, so when needs are met here, we’re taking the river algae to the technicians. They can use their mysterious chemistries to extract materials for self-repairing sail production. You want anything today?”

“No need, no need. Only when I saw you had so much, it inspired me. I have an idea for a new recipe I wouldn’t mind serving up at the tavern today …”

Ben wandered off to his next stop at the witchcrafters while his big dad invited the rivermen over for a hearty meal, whether or not they had sugar kelp to spare. Auntie Cade followed the boy, sure he was eager to play with the puppies Auntie Owen had been bringing to the circle while they all talked story and swapped dyeing methods and stitch techniques. But Auntie Cade soon realized that she’d lost sight of the boy. He had veered off from his usual route and she searched the crowd at knee height, looking for him, fighting back a strange shame — an auntie never loses sight of their child. (Though Auntie Cade is quite extreme in her sense of responsibilities. She doesn’t permit herself to make mistakes, when everyone else knows that aunties are only human.)

Then she saw him. Tottering over to a man she didn’t recognize. Not a neighbor, perhaps a neither. That’s what we call people who we don’t yet have a named relationship with. You call them strangers, which … rude. But the man was sitting crouched off to the side with his head down and his cupped hands held out. Ben had noticed him, probably glimpsed between the legs of passersby, and had left his prescribed route to answer him.

Ben slipped his tiny hand into the man’s empty cupped ones.

The man looked up, startled, and opened his hands to find that Ben had placed the glassmaker’s marble there. The colorful work of magic. The cold miniature world.

Tears streamed down Auntie Cade’s cheeks when she saw Ben take the man’s hand, urge him to his feet and lead him over to the puppies. She knew how Ben felt about holding hands, that he endured his own discomfort to give comfort to another. She hurried the few steps back to Jibril and tearfully recounted what had just happened. How Ben had recognized the man’s need, and he had responded. This was unmistakably a word. Ben’s first.

They embraced and laughed and wove through the crowds to the witchcrafters’ circle. They found Ben silently introducing the man to the squirmy puppies, even then showing his abilities to be attuned to the nonverbal needs of creatures, human and otherwise.

I’m sure you know that’s not the end. How could a first word ever be?

But you didn’t need a story about an ending. I saw that right away, the first time we met there in the beginning. Saw how I would have to unspool my narrative thread into loose loops and coils to ensnare you. My needle sharp and glinting to repair the tears. It’s a story, I hope, that will hold to bridge the short century between us. A tightrope that will help you find your way back here.

Even now, you’re wondering how a storyteller from the future could be telling you all this. The, like … mechanics of the thing. See, storytellers are time travelers. Always have been. Or at least they could be, if they understood their true relationship with time. I’m not sure the blip storytellers were able to do this. The records of their stories would read differently if they could … though maybe the ones who understood the weavings of time didn’t get the opportunity to leave records. (I’ll have to talk with Winslowe about that one — archivists aren’t wrong all the time.)

I’m not predicting the future. I’m just telling you what I’ve seen and been told. So the next time you find yourself holding on to an imperfect blue marble, you might have a few ideas about what to do with it.

Rae Mariz (she/her) is a Portuguese-Hawaiian speculative fiction storyteller, artist, translator, and cultural critic with roots in the Big Island, Bay Area, and Pacific Northwest. She’s the author of the Utopia Award-nominated climate fantasy Weird Fishes and cofounder of Toxoplasma Press. Her short fiction has appeared in khōréō magazine and made the shortlist for 2023 IAFA Imagining Indigenous Futurisms Award. She lives in Stockholm, Sweden with her long-term collaborator and their best collaboration yet.

Carolina Rodriguez Fuenmayor (she/her) is an illustrator from Bogotá, Colombia.