Imagine 2200, Grist’s climate fiction initiative, celebrates stories that invite us to imagine the future we want — futures in which climate solutions flourish and we all thrive. Discover the 2025 contest winners. Or sign up for email updates to get new stories in your inbox.

The cocoons glowed like pebbled moons. A stray moth brushed Grace Chan’s cheek, flying toward the single lamp above her head. Normally the silkworm nursery was filled with chatter and laughter as she and her grandmother, Nai Nai, laid out fresh mulberry leaves for the worms. But tonight, Grace only heard the moths’ flapping wings and New York City’s cicadas through the nursery walls.

It’d been a month since Grace placed Nai Nai’s urn next to her grandfather’s, mother’s, and father’s urns on the family altar. Every day, after Grace flipped the OPEN sign to CLOSED and locked the restaurant door, she made sure to serve one last meal. She placed sesame oil dandelion salad in front of the altar photo of Mama, pickled chicken of the woods for Baba, and of course, any leftover fried silkworm for Nai Nai and Ye Ye. She swept away yesterday’s ashes and lit new incense sticks. And as the red incense burned down, giving off its woody smell, Grace talked to her family.

“Quique came by today. They’re going to start growing seaweed on the farm and he asked if we want the first batch. I asked for a sample but I’m already thinking we could try some of Ye Ye’s recipes. We could do a soup. Or what do you think, a salad?”

Grace chatted away to the photos of her parents and her late grandparents as she wiped down tables and stacked the plastic chairs. And for a moment, Grace felt like she was with her family again: Nai Nai watching soap operas on the rabbit ear TV at the front of the house, Mama tallying the register, and Baba dicing garlic mustard through the kitchen window. But as the floors gleamed, and the worn counters sloughed off their spills, no one ever responded back to Grace.

By the end of the night, Grace’s last task was to check on the silkworms. Only in the back room, cocooned in the dark with the worms, did Grace truly feel the restaurant’s silence. The aroma of dried decaying plants and the soft fuzz on mulberry leaves always called Grace back into her body. But her return felt like no homecoming. Grace only remembered that if a pupa emerged from its cocoon into a moth, it could parent up to 300 eggs, but after that, the moth would stop its marvelous flying and orphan the eggs for the rest of their brief lives.

“The first silkworm keeper,” Nai Nai told her, “was an empress.”

The legend goes: Empress Leizu was sitting under a mulberry tree when a silkworm cocoon fell into her tea. While the cocoon soaked in its hot bath, a thread separated. Leizu wrapped her finger around the thread’s end. Her ladies-in-waiting pulled the cocoon and it unraveled eight times around the entire palace garden.

The Chans had their own legend: “After the ninth epidemic of mad cow disease, everyone was already eating insects. So we weren’t the first restaurant in PuertoChina to do it,” said Nai Nai.

Nai Nai often told these stories while she and Grace squatted in a corner of the kitchen, soaking the cocoons in steaming hot water. Grace always liked to stir the paddle, loosening any stray dirt or leaf debris off the floating swaddled worms. It was Nai Nai’s role to take the washed cocoons, and with a deft hand and a sharp knife, pluck out the plump meat inside. Clean and quick.

“But no one,” said Nai Nai, finally getting to the part Grace liked best, “no one was serving silkworm on Canal Street. Not until I opened up the first restaurant! And they couldn’t get enough of it. I got the idea when I was walking past Mulberry. The city was planting more trees, and I thought, ‘You know, there used to be mulberry trees on Mulberry Street. Why don’t we bring them back?’”

Grace had heard all these stories time and time again. Nai Nai planting an avenue of mulberry trees. Nai Nai and Grace’s grandfather, Ye Ye, buying the first brood of silkworms (five of them, smaller than her pinky toenail) and raising them until there were hundreds. Grace also heard about the restaurant’s opening day, where Ye Ye wore a moth-patterned custom suit, and Nai Nai wore a matching dress.

After the restaurant’s opening, it became a flipbook of family stories and snapshots: Baba doing his homework behind the cash register while taking orders; the derelict office buildings surrounding the restaurant transforming into neighborhood farm plots; New York City workers replacing concrete sidewalks with permeable pavement to save PuertoChina from flash storms; the restaurant closing down for the day on its 10th anniversary, in the midst of the last bad bird flu mutation, as the Chans and everyone from Plot 685 attended Ye Ye’s funeral.

Through it all, the restaurant survived. It endured. And it served the best damn deep-fried Sichuan silkworms anyone was going to find in PuertoChina. Hearing Nai Nai’s stories made Grace feel like she was tied to Empress Leizu’s long silk thread. A royal lineage that refused to be cut.

Nowadays, even as Grace visited Plot 685 by herself for all her restaurant staples, and as Grace fried pupae, ground mealworm, and pressed tofu for all the regulars, she desperately retold herself Nai Nai’s stories. She belonged to a long line of silkworm keepers, Grace reminded herself. Beginning with a mighty and beautiful empress. But with each passing day, the stories felt less like an anchor, and more like Grace herself was a stray kite, fighting not to rip off and spiral away into a howling wind.

In the blue dawn morning, Grace was already awake and going over her kitchen checklists. A fan oscillated in the corner, blowing the paper on her clipboard every time it turned. Grace could already feel summer’s fire, another heat wave threatening to invade the city.

At around 6:15 a.m., right on time, a sound banged three times on the backdoor. Grace never stopped counting jars of dried beach beans even as she reached over and opened the back door for Quique Flores.

“Where do you want these?” asked the farmer, carrying a crate full of watercress. Finally, thought Grace. Quique’s floating farm on the East River was one of the few that could grow the volume of specialized produce she needed. Quique’s quality was consistent but his deliveries could lag.

“You can set them over there,” said Grace, continuing her beach bean count.

Quique set the crate on the counter and wiped his brow. Sweat was already beading on his tanned skin. “So I got good news and bad news,” Quique said. “What do you wanna hear first?”

“Thirteen, 14, 15 — one second,” Grace said. When it came to Quique, her manners evaporated back when they were kids and Quique dangled spiders over her head.

“Twenty, 35, 17,” interrupted Quique.

Grace spun towards Quique. He grinned underneath a briar patch of unshaved stubble, pleased with himself. “You’re so annoying.”

“I needed your attention.”

“You get five seconds.”

“Good news or bad. Pick.”

Grace turned back to her beach beans and tried to remember where she left off. “Good.”

“Watercress had a great season. So I think you’ll be happy with the quality.”

“We’ll see. I’d like to check.”

“How long have I been selling produce to you, Grace? And in all these years, have I ever sold you anything bad?”

“You’re just mad I criticized your morels last season.”

“They were perfectly good morels.”

“You’ve grown better. So watercress is good. Supposedly. What’s the bad news?”

Quique suddenly grew serious. It was strange.

“You know the stormwater system?” he said.

“Which one?” asked Grace, her stomach knotting. There were hundreds of systems set up around the city meant to catch rainwater during flash storms. All over New York City, every drop of rain fed into filtered underground reservoirs. The water network let every neighborhood survive the intense summer heat waves, watered their farms, and kept their homes safe from flooding. But Quique knew Grace well enough to know there was only one reservoir that mattered to her.

“Grand Street,” he said. “The one for your mulberry trees? It’s not collecting like they’d expect.”

“What do you mean?”

“The water levels don’t match with the rainfall we’ve been seeing. Issa said they already started working on it. The trees should be all right. They’re pretty drought-resistant, and yours are pretty mature —”

“But if the reservoirs aren’t full when the next heat wave hits then the leaves might get damaged, or … or … or they might —”

“I know, Grace,” said Quique, his voice soft. “I asked them about the levels. There’s still water in the reservoir. There’s just something going on with the collection system.”

Grace’s chest tightened as she pictured the next two months of heat waves and her grandmother’s trees: their roots shriveling below the dirt, their silver leaves drying brown and yellow, making them useless for the silkworms to eat. It was a terrible premonition: a nursery, filled with starved, dead silkworms. A shell of a restaurant.

Grace barely heard Quique as he said, “I’m keeping a pulse on it, but I wanted to let you know since … well, I know your grandmother planted those trees.”

Grace blinked until her eyes stopped stinging. If she was going to cry, she wasn’t going to go and do it in front of Quique Flores and embarrass herself. Instead, Grace cleared her throat and crossed her arms. “Well that settles it,” she said.

“Settles what?”

“Let’s take a walk.”

The faded subway sign swung in the wind: “GRAND STREET STATION.” As Grace and Quique descended into the station, past the geometric tiled murals along the cool walls, it was hard for Grace to imagine the stairwells once packed with millions of people, waiting for trains that ran on dry land stretching as far as the Bronx. The only way there now was an hour by boat.

Inside the station, rushing water and humming machinery met them, along with a muscular woman with a crown of tight braids. Quique greeted her by name. Issa, the water foreman.

“We think there’s blocks in the major pipes,” said Issa. “That’s why the water’s not collecting.” She had to shout above the machinery so Grace and Quique could hear her.

“Can you fix it?” asked Grace.

“Should be an easy job. We could do it in a day, but I got a burst pipe on Astor Place and I need all hands on deck down there. We’ll get to it when it’s done.”

Grace frowned. “There’s another heatwave coming.”

“Sure, in two weeks.”

“You know the weather’s unpredictable.” Grace knew how she sounded, how intense she could get. Her family called Grace their “little bull.” Slow down, they used to tell her. But without them here, Grace had no reason to stop and every reason to press.

“Can’t you spare someone to fix it this afternoon?” she insisted.

Issa’s face soured. “I already got one guy logging the locations. That’s all I can spare.”

“What about one more?”

Issa raised her eyebrows and looked at Quique with the silent question, Is this girl serious? Quique glanced at Grace and with her expression, Grace let him know that yes, she was very serious, and she was prepared to let everyone know how serious she could get. He turned back to Issa, Grace was sure, to apologize for her behavior.

“Where is he?” Quique asked Issa instead. “Your guy?”

Issa’s guy turned out to be a lanky and pale intern. Quique and Grace found him up by Second Avenue. “We think the blocks could be here, here, and here,” said the intern, pointing at spots on a map.

“Great. Drive us there,” said Grace. If she needed to miss the lunch rush, then so be it. The restaurant could survive one afternoon without it.

“Where to first?” asked Quique.

“You’re not headed back to the farm?”

“And leave you alone? No, I’m staying. Besides —” Quique lowered his voice so it was right by Grace’s ear. “Someone needs to protect that intern from you.”

A surprising warmth bloomed in Grace’s chest at Quique’s nearness. She rolled her eyes. “Thanks,” she said and turned away from the smiling farmer, her cheeks flushed sun-hot.

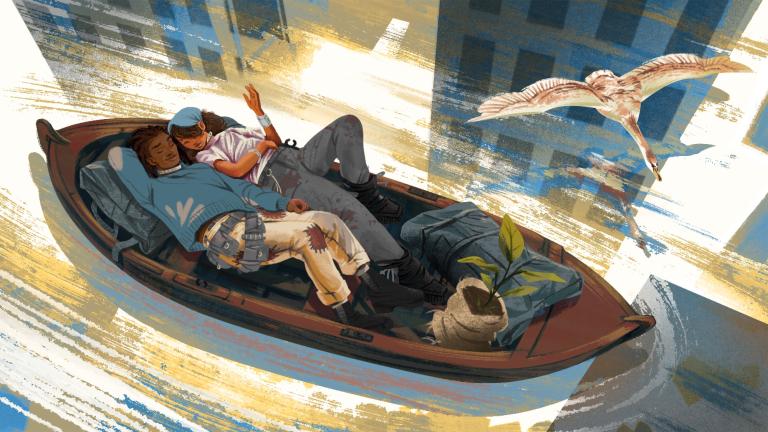

The intern drove them on a jalopy golf cart. Grace clutched the cart’s roof strut as they bounced over gravelly roads. The avenue took them toward the banks of the East River. Cattails lined the muddy riverside while sunlight glinted off the floating solar panels on the water. White osprey loitered among the reeds. They took to the air as the cart zipped by, flying over the oyster reefs growing on discarded subway cars surrounding the Manhattan archipelago.

The intern parked in front of a large pipe. He pulled out tools and walked with them to the opening. “First we’ll scrape out what’s inside,” said the intern. “We have extra —”

Grace didn’t wait for him to finish. She picked up a long stick with steel bristles on the end. She snaked it up the pipe and pulled; it stuck. Quique grabbed the handle and together, they yanked out the debris from the pipe. Rotting leaves, wood mulch, and mud tumbled out, vomiting over their pants and shoes.

Quique coughed when the smell hit.

The intern watched from a distance. “I was going to mention we have extra suits,” he said. “But that works, too.”

At the last pipe on Broome Street, Grace wiped her forehead, leaving something thick and wet across her forehead. Dark, gloopy clay dried on Quique’s shirt. Overhead, dark clouds covered the sky and a wind blew through the city’s mossed and concrete alleyways.

“You guys are fast! I’m impressed!” yelled the young intern from the golf cart.

“Thanks for driving us,” Quique said flatly as he returned their tools to the intern, still fresh in clean clothes.

The intern grinned brightly. “No problem! You guys want a ride back?”

Around the corner, Mulberry Street called to Grace. She had to go and see her grandmother’s trees for herself.

“You go ahead,” Grace said to Quique. “I’m gonna make one more stop.”

Soaked in sweat, grime, and mud, Quique asked, “Where’re you headed? I’ll come with.”

Why? Grace wanted to ask. But she suddenly felt worried what Quique’s answer might be, and if it could be different than what she was suspecting. “You sure?” she asked slowly.

“You can’t get rid of me that easy, Grace Chan.”

The tan mulberry trees ran along the empty street, and she and Quique were alone. Everyone had already run inside as thunder growled in the distance. Grace approached her grandmother’s trees. Their green, serrated leaves fluttered in the quickening wind.

Grace felt the first rain drop. Then the second. Until it was storming. Water drops pooled into puddles around her and Quique’s feet. The rain felt like a curtain drawn around her, hiding her like she was a girl sheltering behind her grandmother’s skirt. And because these were her trees, and because it was only her and Quique out on the street, Grace leaned her forehead against the rough bark.

“Drink up,” she whispered, and the sky cracked open.

Somewhere, all over the city, the rain sloped off slanted solar paneled roofs. It filled the vegetated swales, and rippled the surface of the Hudson and East River while below, the city’s graveyard of flooded and abandoned buildings peered up at the thundering sky. And here, underneath Grace’s forehead, trees her grandmother planted almost 40 years ago, would survive another summer.

Quique’s fingers brushed her back. Electricity crackled along her skin.

“Come on,” he said. Up close, Quique’s eyes were hazel. She wondered if they’d always been that color. “Let’s go. You’re getting soaked. And you owe me a lunch.”

Back at the restaurant, Grace’s knife tapped against the scored wooden cutting board as she sliced ramps, releasing their oniony smell. Wild mustard oil bubbled in the pan. She took the one red chili pepper, grown from Quique’s garden, and diced it. The plump, rinsed pupae sat in a steel bowl. Grace patted them dry before tossing the ramps and chili in with the meat. She crushed a handful of citrusy spicebush leaves, and sliced wild ginger into the bowl and gave it all a quick mix before tipping everything into the oil.

It popped. Fragrant steam hit her face. The ginger, onion, chili, and pupae simmered together, crackling in the mustard oil. Grace rolled up her sleeves, and like Nai Nai showed her, she gripped the skimmer and flicked her wrist so everything in the oil fried evenly.

Grace carried the fried silkworms and steaming bowls of wild rice to where Quique sat in the dining room. Lunch was served. Quique immediately drowned his dish in hot sauce; Grace bit into a crunchy shell, savoring the meat’s firm, creamy, and nutty bite underneath. It might’ve been Grace’s best batch yet, she thought. Quique’s fork, furiously scraping against his bowl, sang in agreement.

When they were done, Grace poured cold tea into Quique’s cup. Rain tapped against the window.

“Thanks for lunch,” he said.

“Thanks for …” Grace hesitated, thinking about the afternoon. “For helping me with the mulberry trees,” she finished. “I would’ve been devastated if anything happened to them. Probably would’ve left PuertoChina for good.”

Grace wasn’t sure if it was the rain clouds filtering through the restaurant window, but Quique looked troubled. “You ever think about it?” he asked. “Leaving?”

“I don’t want to. I’d miss the neighborhood too much. It feels like a part of me.”

Quique was smiling again. “I know what you mean. We Floreses have been here forever. I can’t imagine being anywhere else. My great-grandpa says when the flooding got really bad, all the rich folks in the city packed up first. Then, it was anyone who had someone outside the city. Everybody else got left behind. Our family was too poor to go anywhere.”

“More like too stubborn,” said Grace, smirking.

Grace never noticed how Quique’s eyes crinkled when he laughed. Or how he laughed with his whole body, stomping his feet and slapping his knee. She never realized how pleasant it was to watch him laugh.

Quique wiped his eyes. “What’re you talking about? Us Floreses are easygoing and never have an opinion about anything.”

He glowed when Grace giggled.

“We could move now,” said Quique. “If we wanted to. But I can’t imagine leaving the city. Or the farm. It’s, well, a pain in the ass. But it’s my pain in the ass.”

She thought about her grandmother’s mulberry trees. “I feel the same way,” said Grace.

Outside, the storm was letting up. The rain grew softer against the restaurant window until it stopped. Red sauce pooled at the bottom of Quique’s plate like warm blood ready to pump through a fluttering heart. Grace oddly wished he wasn’t done eating. The afternoon cleaning pipes together had been, well, nice.

“Did you know mulberry fruit makes great tarts?” she asked.

“How come you never made me one?”

“Why won’t you discount the watercress?”

“Make me a tart and I’ll think about it.”

“How about I make you a tart and you give me a discount,” she said. Grace was smiling. It surprised her. She thought in the past month, she’d forgotten how to, and in the sun-lit dining room, Quique was smiling back in a funny way, like Grace had made a joke, but she didn’t think she’d said anything funny at all.

The clock hand ticked towards the late afternoon. She’d already missed the lunch rush. Grace needed to go and get ready for dinner service. Quique needed to get back to his farm.

“Have you ever seen the silkworm room?” she asked.

The overhead light hummed after Grace clicked the chain, and she and Quique squeezed into the warm walls of the nursery. The silkworms spun their cocoons, wrapping themselves in their ivory mantles among the green mulberry leaves.

Grace always grew drowsy among the worms. It was warmer here than other parts of the restaurant. Inside the dimly lit silkworm nursery, she always felt like she was somewhere between sleeping and awake. She heard the moths flit among the shelves, laying their pearled eggs, and felt Quique next to her.

“So this is where it all happens,” he said.

Grace could smell the summer heat on Quique’s skin. The space between them felt unbearably close and unbearably far.

Quique noticed her staring.

He leaned in and said, “Could I, um … Do you maybe want to, well, do you want to— ” he kept faltering. In the dim light, Grace saw he was sweating. Quique Flores, nervous? For once, Grace decided to go easy on him.

She kissed him. His lips answered back, soft and hungry, and she savored the taste of his mouth. They bumped into the silkworm racks, sending ivory moths flying into the air all around them. With that kiss, Grace suddenly became aware of a space growing inside of her. Like how one might notice the size of a room only after someone has entered it. She wanted to laugh as she pressed her body against Quique’s. She had spent days and nights running her hands over the empty room of absence, certain it would become her home. What a joy it was to be surprised. What a pleasure it was to be wrong.

As Quique’s hands gripped her hips and her fingers twined in those forever rumpled curls, Grace thought she couldn’t wait to tell her family the unexpected and happy news: She was falling for Little Enrique “Quique” Flores, and then she remembered.

“What’s wrong?” asked Quique when Grace pulled away.

The tears dripped before she could stop them.

“Am I that bad of a kisser?” he joked. But Quique already knew. Grace didn’t need to explain.

The moths fluttered in circles around them. He pulled her back into his arms, his head resting atop hers as he rubbed her back and she cried against his chest, taking in the smell of dirt and sweat in the crevices of his shirt, feeling both grateful he was there and devastated that her family was not. But joy never asked for permission to keep living. It simply and stubbornly went on. And once Grace quieted and Quique wiped her face, and Grace answered softly that yes, she was okay, and the moths rested on her clothes and Quique’s hair, Grace heard a quiet voice call from somewhere inside her body.

Go on, it said. Live.

K.J. Chien is a Taiwanese American writer based in New York City, where she lives with a much-beloved dog and an equally beloved partner. You can find her past and forthcoming works at kjchienwrites.weebly.com.

Stefan Große Halbuer is a digital artist from Münster, Germany, who has worked for brands like Adidas, Need for Speed, Samsung, Star Wars, Sony, and Universal Music, as well as for magazines, NGOs, and startups. Recently, he released his first solo book, Lines, a coloring book with a selection of his art from the last years.