Yosemite. Big Sur. The Grand Canyon.

When one thinks “wilderness” in the United States, the mind often goes to the American frontier or federal lands in the West.

But for those who live in the South, in the dense forest and mountain ranges of Appalachia, next to the greenery and historical richness of the Great Dismal Swamp in Virginia and North Carolina, or near natural wonders like Mammoth Cave in Kentucky, wilderness has a different meaning. The Southeast U.S. is one of the most biodiverse temperate regions in the world, handily beating out the Western U.S. when it comes to the number of endemic species.

But most of the Southeast’s biodiversity isn’t formally protected, and it’s at risk, thanks to a long history of development, tree farming and logging, coal mining, and the introduction of invasive species. (The American chestnut, for instance, once a prominent species throughout Appalachia, was decimated in the 1900s after the introduction of an East Asian fungus.) Ecologists and environmental advocates say that the region’s biodiversity can be saved — if we can learn to value its natural resources the way we value those of the American West.

“It takes a lot of people that are committed to the region to work really hard for a long time” to protect wilderness, according to Travis Belote, a research ecologist for the advocacy group The Wilderness Society.

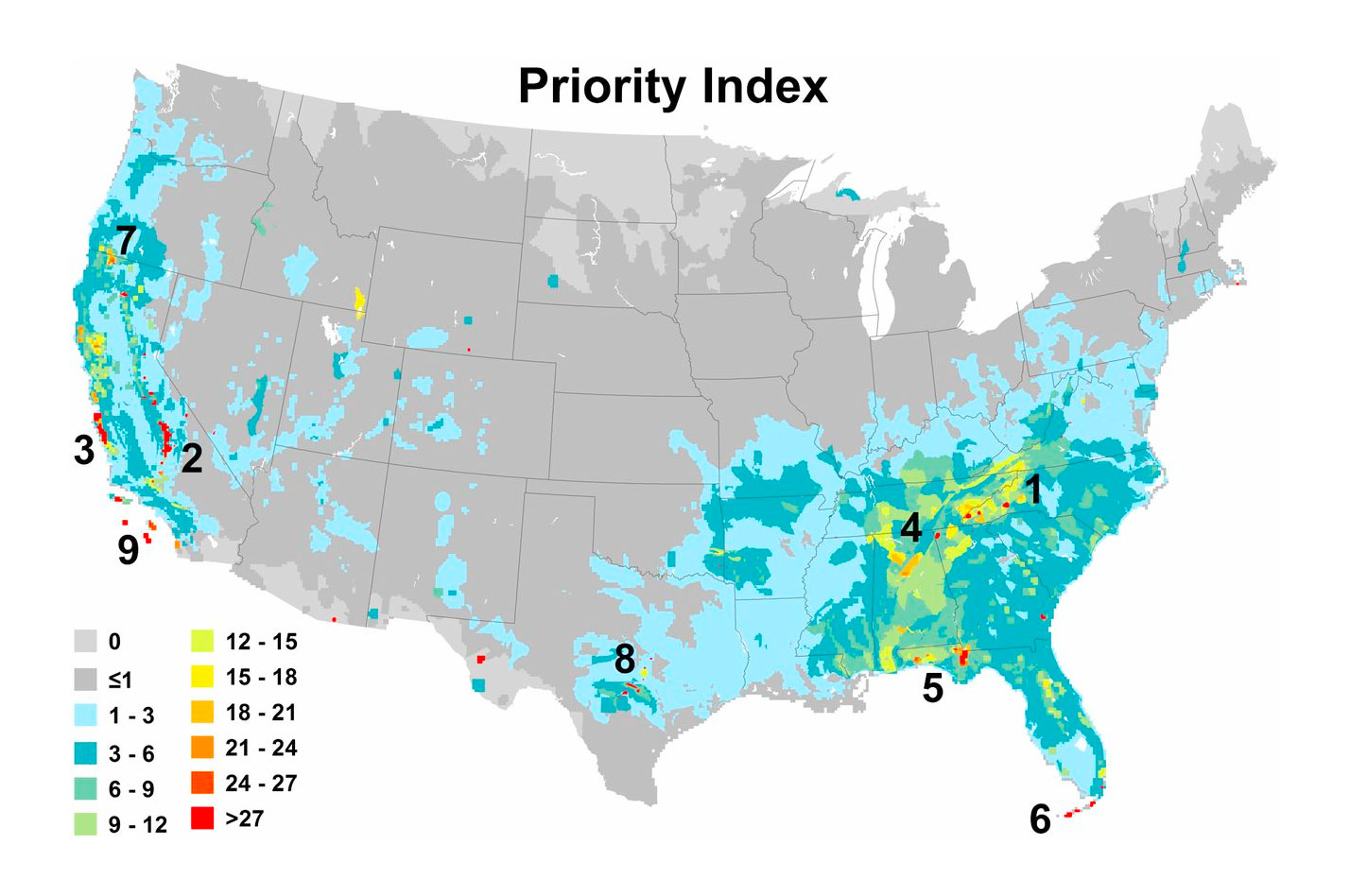

Recommended areas to prioritize for conservation expansion based on combined species richness for mammal, bird, amphibian, reptile, freshwater fish, and tree taxa throughout the U.S. Jenkins, C. N., Van Houtan, K. S., Pimm, S. L., & Sexton, J. O. (2015). US protected lands mismatch biodiversity priorities. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(16), 5081-5086.

The disparity in how we treat wilderness in the East and West comes in part from the direction of European colonization, which started on the East Coast and slowly spread westward throughout the 19th century. “As we were spreading west, we were quickly taking land that wasn’t ours and deforesting it in the process,” said Sam Davis, conservation scientist for the Dogwood Alliance, a nonprofit organization dedicated to the protection of Southern forests. “Between 1880 and 1930, we managed to deforest about two-thirds of the East Coast,” said Davis, thanks in part to sawmill technology advancements and the creation of railroads that made the processing and shipping of timber easier. In the years since, fossil fuel industry practices like mountaintop removal for coal mining, offshore oil drilling in the Gulf and along the Atlantic, and fracking in Appalachia’s Marcellus Shale formation have further threatened biodiversity — not to mention the climate and the health of the often Black and Indigenous communities living nearby.

Meanwhile, during the settlement of the West in the 19th century, it wasn’t so easy to exploit the land for profit — the mountainous topography in the West wasn’t desirable to farmers and ranchers. And in the late 1800s and early 1900s, early environmentalists and naturalists like John Muir and Theodore Roosevelt began to promote the need to protect wilderness from development, said Davis. In 1872, Congress established Yellowstone as the first national park, followed in 1890 by Yosemite, which Muir advocated heavily for. During his time in office in the first decade of the 20th century, President Theodore Roosevelt established 150 national forests, five national parks, and 18 national monuments, the vast majority in the West — and the National Parks Service hadn’t even been established yet.

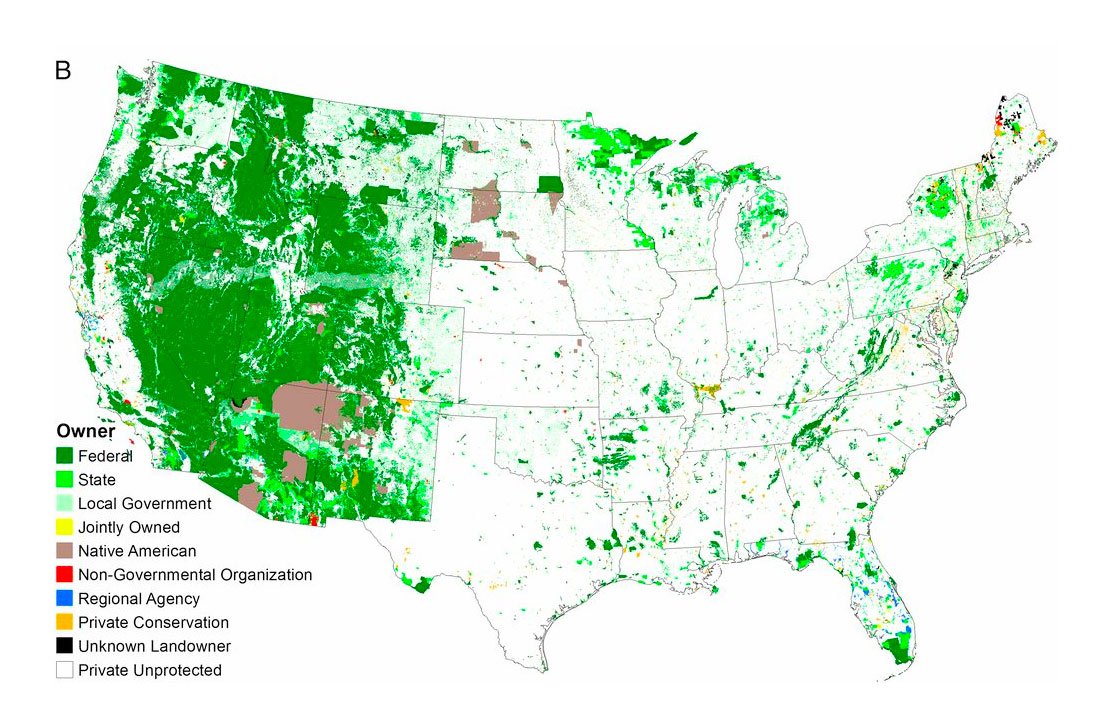

“It wasn’t as occupied in the West, and so it was much easier for the federal government to take those lands and hold them,” Davis said (though, of course, Native American populations had been inhabiting these regions for millennia). Most land in the Southeast is privately held, having been sold off and settled early on after colonization, but the federal government owns almost 50 percent of land in the West.

Ownership status of lands in the United States. Jenkins, C. N., Van Houtan, K. S., Pimm, S. L., & Sexton, J. O. (2015). US protected lands mismatch biodiversity priorities. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(16), 5081-5086.

In the East, places like the Great Dismal Swamp National Wildlife Refuge present a rare example of federally protected wilderness. But even the parks and national forests that are protected, like Jefferson National Forest in Virginia and West Virginia or Nantahala National Forest in North Carolina, are available for limited commercial use (although environmental organizations often organize and litigate against this commercial use).

A bigger problem when it comes to protecting Southeastern biodiversity, though, is that so much Southern wilderness is privately owned. And because economic growth is so closely tied to the landscape, individuals who do own land will often use their trees or their resources as a reluctant source of revenue.

Belote says that that decision is understandable. “If you own 100 acres in southwest Virginia or northeast Tennessee that’s been in your family for 100 years or more, and you don’t have much income, and you have an opportunity of making some money on selling your timber, how can you say that that shouldn’t be on the table?” he said.

Clinton Jenkins, associate professor in the earth and environment department at Florida International University, said that the solution is in finding uses for the land that are both profitable and sustainable, like selling the land for the creation of parks, or installing tourist attractions like country bed and breakfasts.

The Dogwood Alliance is thinking along the same lines, promoting the protection of land in the Southeast for wildlife and recreational purposes. For example, the group has been working with the Pee Dee tribe in South Carolina to protect places like the Pee Dee Wildlife Refuge from pollution from wood pellet operations.

“There are a lot of strategies,” Davis said, noting that state and local parks and protected areas can protect biodiversity just as well as Western-style national parks. Creating wildlife refuges, parks, and protected areas to be used as tourist attractions in the region would bring a different revenue stream into the South, and some much-needed jobs in an area where the pandemic has led to massive job loss, all while providing additional opportunities to engage with green space for local residents. Spaces like the Pee Dee and Great Dismal Swamp Wildlife Refuges allow activities like fishing, hunting, and bird-watching, and it’s estimated that wildlife refuges like these produce about $2.4 billion in economic output annually nationwide.

“The tourism industry in the South should be much bigger than it is, because there are so many cool things to do in the South,” said Davis.

The feasibility of such a switch is uncertain. It depends on whether property owners would be willing to sell their land for recreational use and whether demand for the energy and timber coming out of the Southeast decreases enough to allow for public land conversions. Finding the public funds to purchase private lands right now is also a concern; in the midst of a pandemic-caused economic crisis, it would take a real push from the public to allot funding for the conversion of private land into public parks. And tourism brings its own ecological challenges, like increased litter, pollution, and noise.

But a recreational solution may be the best and most economically sound strategy for preserving what ecosystems and species remain in the Southeast.