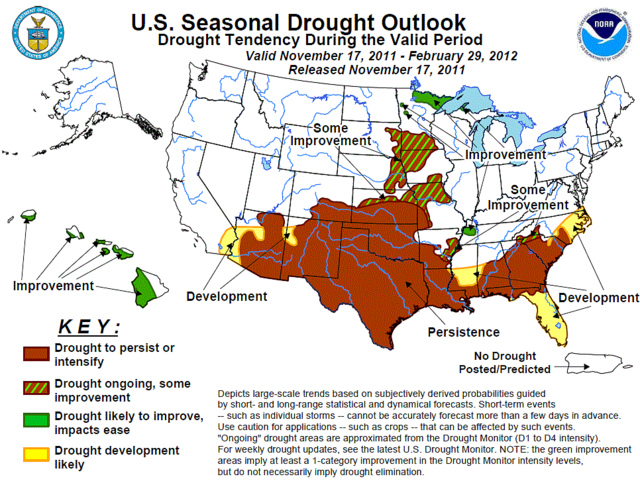

Texas’ water problems won’t be over anytime soon.Photo: SeanIn case anyone missed it, Texas had a big drought last summer — the worst one-year drought in the state’s history. Lakes dried, animals were slaughtered, cities imposed lawn-watering restrictions, the governor prayed for rain. Among the doom-and-gloom sector of the left, talk has been circulating of Texas as a failed state.

Texas’ water problems won’t be over anytime soon.Photo: SeanIn case anyone missed it, Texas had a big drought last summer — the worst one-year drought in the state’s history. Lakes dried, animals were slaughtered, cities imposed lawn-watering restrictions, the governor prayed for rain. Among the doom-and-gloom sector of the left, talk has been circulating of Texas as a failed state.

That’s easy to dismiss as tit-for-tat revenge for Texas’ age-old talk of secession; after all, droughts end, and places recover. Unless they don’t: When one takes a hard look at Texas’ water supply, and plans to build nine water-intensive coal plants, it becomes clear that the state’s apocalyptic droughts are more likely to become the norm than the exception.

The state’s water shortage is structural, warns the Texas Water Development Board. Currently the state needs 18 million acre-feet of water, and it has 17 million acre-feet available to it. Aquifers deplete. Population grows. By 2060, the state is expected to need 22 million acre-feet, but only have 15.3 million acre-feet available to it. Because some dry places simply can’t have water piped, the total shortfall is projected to be 8.3 million acre-feet. Roughly, the state will have two gallons of water available to it for every three gallons it needs.

Houston, we have a problem.

Currently, 18 cities are high priority — they’ll either run out of water within six months unless the rains come, or they don’t know how much water they have. Texas’ water supply for the future is uncertain, and the health of Galveston Bay, home of the state’s most commercially productive estuary, is in jeopardy. Last week, voters approved one of two water-related measures on the ballot — a water bond to build dams, but that’s no short-term solution for a state whose wildfire “season” is now over one year old.

In the meantime, the state is blithely planning multiple power projects to meet projected population growth — nine coal plants in planning stages will be added to the 19 to 20 coal-fired power plants already in the state.

Most electricity power plants require large amounts of water. How large? Short answer: a lot, but no one knows. Medium answer: Thirsty power plants threaten watersheds, and Texas’ coal plants are among the nation’s thirstiest:

Coal-fired plants alone account for 67 percent of freshwater withdrawals by the power sector and for 65 percent of the water completely consumed by it, the report said. Newer plants include air-cooling or “dry cooling” technologies, but so many plants rely on water-cooling that they accounted for 41 percent of the withdrawals of freshwater in the United States in 2005, according to the United States Geological Survey.

In more detail, a Union of Concerned Scientists report on freshwater use by power sources begins by noting the impact on drought-stricken Texas:

As of late summer 2011, Texas had suffered the driest 10 months since record keeping began in 1895 (LCRA 2011). Some rivers, such as the Brazos, actually dried up (ClimateWatch 2011). The dry weather came with brutal heat: Seven cities recorded at least 80 days above 100 degrees F (Dolce and Erdman 2011). With air conditioners straining to keep up, the state’s demand for electricity shattered records as well, topping 68,000 megawatts in early August (ERCOT 2011).

An energy-water collision wasn’t far behind. One plant had to curtail nighttime operations because the drought had reduced the amount of cool water available to bring down the temperature of water discharged from the plant (O’Grady 2011; Sounder 2011). In East Texas, other plant owners had to bring in water from other rivers so they could continue to operate and meet demand for electricity. If the drought were to persist into the following year, operators of the electricity grid warned, power cuts on the scale of thousands of megawatts are possible (O’Grady 2011).

State planners have begun to notice the water-intensive nature of coal plants. The White Stallion coal plant, near Bay City, south of Houston, planned to take water from an estuary rich in oyster and shrimp nurseries. Even after promising to switch to a less water-intensive dry-cooling plan, the project has been opposed by farmers who don’t have water to sell. This week, the Lower Colorado River Authority recently rejected a water contract that would have given White Stallion a 25,000 acre-feet-per-year water permit. Citizens of Sweetwater, in west Texas, were outraged upon hearing that the city was secretly negotiating sale of water rights for a so-called clean coal project.

Texas will stay thirsty. A structural water shortage is a permanent water shortage that can only be solved by a drastic change — less agriculture, fewer people, more water from somewhere else (dams? desalination? Oklahoma?). More coal plants sucking more water from rivers and estuaries is not part of a sane water policy. Some alternatives to coal-fired electricity are just as water-intensive; natural gas power plants are frugal users of water, but extraction of natural gas through fracking uses billions of gallons of water. Fortunately, one electricity source uses virtually no water and is plentiful throughout west Texas: wind energy.