This is part one in a series on “great places.” Read parts two, three, four, and five.

This is part one in a series on “great places.” Read parts two, three, four, and five.

I asked a while back what new vision or principles could unite the left’s fractious coalition. As you probably guessed, I’ve got a pet idea along these lines. It’s a bit out in left field, at least in terms of mainstream political discussion, but I’m fond of it.

The bumper sticker version is: great places. Making the places we live and work more resilient, intelligent, productive, and pleasant. Making places that encourage good physical and mental health. Making places with a sense of common purpose, identity, and pride. Making great places.

An agenda (loosely) based on making great places is attractive for a number of reasons, which I’ll explore in future posts. But one of my favorite things about it is that it cuts across the decrepit political arguments that dominate U.S. politics: small or big government, capitalism or socialism, growth or sustainability.

When Obama was campaigning, he said he wanted to get past the “stale debates” that have clung to American politics like a bad hangover since the 1960s. We were told it was the first election of a new generation. It turns out, though, there’s a large cadre of angry older white men who don’t want to let those debates go. So the media-political complex in America, still largely dominated by older white men, dwells endlessly on a parade of coded resentments like death panels and rappers visiting the White House.

But the rest of us don’t have to play along! We don’t have to take part in these Groundhog Day debates. Believe me, I’m not talking about being a “moderate” or a “centrist” — a position in between two poles of a dumb debate is still dumb. I’m talking about striving to see things with fresh eyes, to think anew about the unique challenges and opportunities of our historical moment. We’re in a time of profound, rapid change and we need an agenda that looks to the future with purpose and confidence.

I doubt the groping around I’m going to do in the next few posts merits that grandiose description, but I do think that a focus on place has at least some potential to reorient politics and bring together several traditionally siloed interest groups and value sets. Over at the Project for Public Spaces, Ethan Kent is thinking along similar lines in a post called “Placemaking as a New Environmentalism,” but while I agree with most of what he says, I think he goes badly wrong in framing this as an extension of environmentalism, which is a specific social movement with is its own set of concerns and political tools. Focused attention to place is something different. It doesn’t need the baggage of any -ism. Resource sustainability is part of it, but so are economic and social sustainability.

Another inspiration for my thinking came from my hometown alt weekly, The Stranger, in its epic post-2004 election piece called “The Urban Archipelago.” It’s written in The Stranger‘s inimitable style, which will sound coarse, partisan, and aggressive to some ears, but it gets at blunt truths:

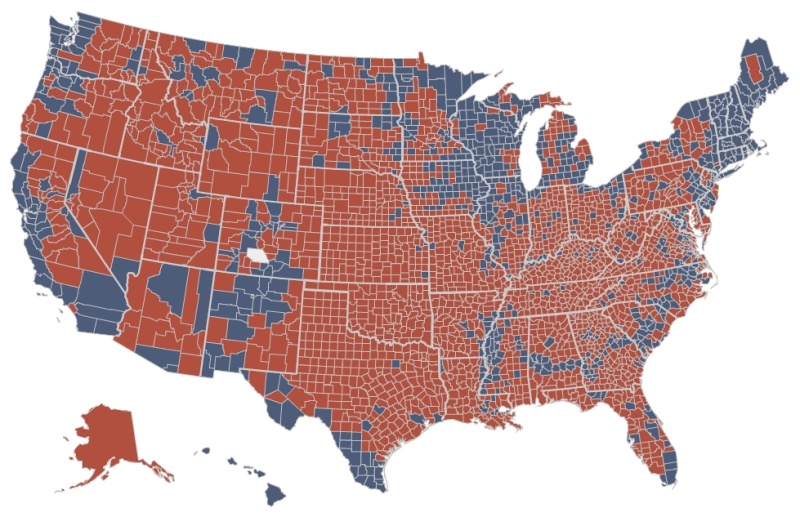

If Democrats and urban residents want to combat the rising tide of red that threatens to swamp and ruin this country, we need a new identity politics, an urban identity politics, one that argues for the cities, uses a rhetoric of urban values, and creates a tribal identity for liberals that’s as powerful and attractive as the tribal identity Republicans have created for their constituents. John Kerry won among the highly educated, Jews, young people, gays and lesbians, and non-whites. What do all these groups have in common? They choose to live in cities. An overwhelming majority of the American population chooses to live in cities. And John Kerry won every city with a population above 500,000. He took half the cities with populations between 50,000 and 500,000. The future success of liberalism is tied to winning the cities. …

2008 county-by-county electoral map.

2008 county-by-county electoral map.

For Democrats, it’s the cities, stupid — not the rural areas, not the prickly, hateful “heartland,” but the sane, sensible cities — including the cities trapped in the heartland. Pandering to rural voters is a waste of time. Again, look at the [electoral] map. Look at the urban blue spots in red states like Iowa, Colorado, and New Mexico — there’s almost as much blue in those states as there is in Washington, Oregon, and California. And the challenge for the Democrats is not just to organize in the blue areas but to grow them. And to do that, Democrats need to pursue policies that encourage urban growth (mass transit, affordable housing, city services), and Democrats need to openly and aggressively champion urban values. By focusing on the cities the Dems can create a tribal identity to combat the white, Christian, rural, and suburban identity that the Republicans have cornered. And it’s sitting right there, on every electoral map, staring them in the face: The cities.

This is what I was trying to get at in my earlier post: If the right has cornered the white rural/suburban demographic, the left needs to gather everyone else and give them an identity of their own.

I’m going with “great places” rather than “cities” because, while there’s no doubt that density is the bedrock principle here (more on that later), the city will not always be the relevant level of analysis. There can be great places inside cities (neighborhoods) and great places that bind several cities together (metropolitan areas). And yes, even smaller cities and towns can be great places (more on that later too). Everyone is of a place.

No matter what term is used, the whole notion will be attacked as elitist, of course. It always is. Many people who live in dense, walkable areas tend to pigeonhole urbanism as elitism. It brings to mind … well, Portlandia. This is obviously a PR challenge, but it’s worth noting that on the merits it’s completely wrong. Families benefit from walkable density too. Kids who walk and bike to school are healthier, and so are their parents. Old people benefit from ready access to services. And everyone — every human being, by dint of simple biology — benefits from more human contact and social connection. Even conservatives are nostalgic for small-town life, though they don’t seem to realize that it was the human scale that made small towns so pleasant. Go to almost any town or city in the country these days and you’ll find people trying to restore walkable downtown districts, add green space and trails, and attract creative young people. No matter our age or political affiliation, all of us would rather live in great places.

So anyway, that’s enough hemming and hawing by way of introduction. In subsequent posts I’ll explore various facets of this idea. I’m going to be racing past a lot of complicated subject matters about which I’m no expert (viva blogging!), so it would be great to hear from folks who know more than I do. Lots of people have been thinking about and working on various aspects of place for a long time; hopefully I can weave some threads together in a way that does them minimal violence.

Next: “Turning from stuff to happiness.”