Verso Books, a self-described “radical publishing house,” was not accustomed to getting airtime on major U.S. television networks — or at least it wasn’t until it published Andreas Malm’s How to Blow Up a Pipeline in 2021. With a punchy argument that property destruction is justified in the face of an ever-worsening climate crisis and a provocative title (the book does not include any practical instructions), Malm found himself at the center of mainstream political discourse.

It’s not that activists should abandon mass action and civil disobedience as tactics in the fight against fossil fuel development, the Swedish academic argues. He just thinks they need to expand their toolbox. In the book, Malm describes taking part in numerous demonstrations over the past several decades, including one at the first annual United Nations climate summit in 1995. Since then, the U.S. has added more than 800,000 miles of fossil fuel pipelines, and Germany has continued to excavate almost 200 million tons of extremely polluting brown coal each year. Clearly, he concludes, blocking intersections and playing dead at U.N. conferences is not enough.

“So here is what this movement of millions should do,” he writes. “Damage and destroy new CO2-emitting devices. Put them out of commission, pick them apart, demolish them, burn them, blow them up. Let the capitalists who keep on investing in the fire know that their properties will be trashed.”

Coming on the heels of a year of massive racial justice demonstrations across the U.S., the book was received with excitement, though hardly all of it was positive. It drew particular ire from Fox News, which published a slew of articles condemning newsrooms like the New York Times and the New Yorker for engaging with Malm’s arguments. On her late-night show, Megyn Kelly pilloried the New Yorker’s editor-in-chief David Remnick for interviewing Malm on the magazine’s podcast.

“How about instead of normalizing this climate terrorism, we talk about how absolutely insane it is,” she lambasted. “To the author who wants to blow up pipelines to help the climate, we say: Thanks but no thanks.”

Malm’s influence, however, appears only to have grown. How to Blow Up a Pipeline attracted the attention of a group of filmmakers who got together and brainstormed how to turn the book into a feature-length movie. The three writers — Ariela Barer, Daniel Goldhaber, and Jordan Sjol — weren’t interested in making a high-grossing blockbuster. They were compelled by Malm’s argument and wanted to create something that could make it tangible.

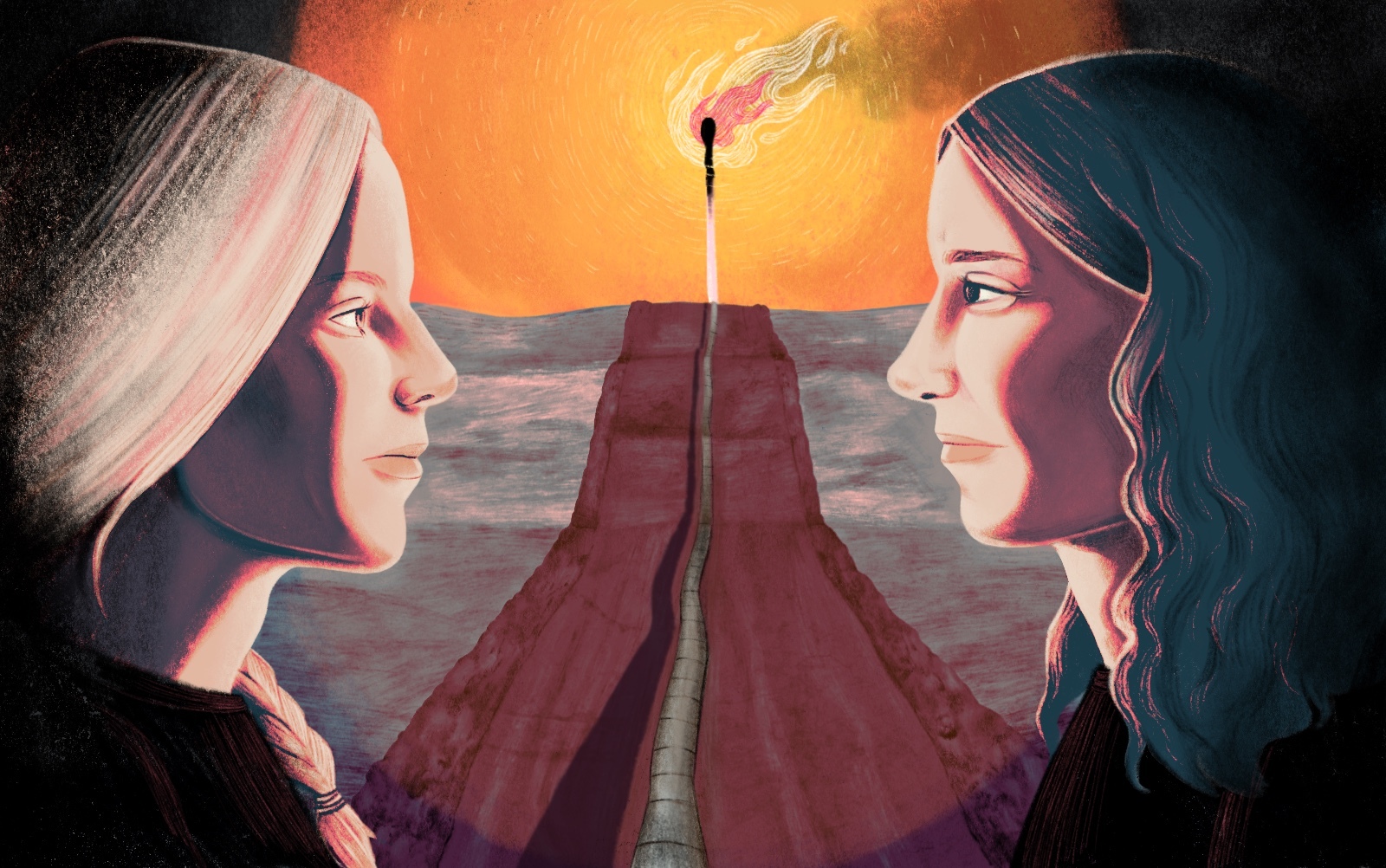

The resulting film, which premiered in U.S. theaters earlier this month, is an eco-terrorist heist thriller that retains Malm’s iconic title while supplying an original narrative inspired by his argument. Following a recent screening at New York’s Angelika Film Center, co-writer and star Ariela Barer said that the filmmakers’ intention was to create propaganda, and in doing so, shift the cultural imagination around how to combat climate change. Her co-writer Daniel Goldhaber, who directed the film, added that the fundamental question at the core of the movie is whether attacking and destroying a pipeline could be considered an act of self-defense.

“From an ethical and moral standpoint, we all sort of recognize that if someone is pointing a gun at you with the intent to kill, you have a right to take that gun away from them and dismantle it,” he said. “The fossil fuel industry has a gun to the proverbial head of the world, and the movie is asking the question: Do we have a right to take it away from them and dismantle it?”

The film’s premise is simple. Eight people from across the country converge on an abandoned house in the desert for 24 hours to execute a plan to blow up a pipeline that snakes through the Permian Basin, the oil-and-gas-producing heartland of Texas. Their hope is that their destruction of fossil fuel infrastructure will inspire others to do the same, and that the cumulative effect will be a meaningful reduction in the extraction and burning of carbon-emitting fuels.

“Structural damage is the point,” one character insists. “I don’t want to rebuild anything,” says another. Blowing up one pipeline won’t shutter the fossil fuel industry, but sparking a series of copycat actions across the country might have a real impact.

The characters know that their extreme tactics will, at least initially, make their movement unpopular. In one scene, the group’s lone skeptic notes that spiking oil prices — the logical result of a widespread blow to fossil fuel production — will hit poor people the hardest. But the film does not linger on these questions; it’s clear that for these characters, the stakes are too high to change course.

As we learn more about who they are, we begin to understand why: There’s a man saddled with debt after fighting the government in court for taking his land to build a pipeline; a young woman whose mother died during a heat wave in Chicago; and her best friend, who has a rare type of leukemia known to affect people who grew up near oil refineries.

These context-setting moments are one of the film’s greatest strengths. They establish the stakes for individuals on the front lines of oil and gas development and make clear that the burdens of industrial pollution and climate change aren’t spread equally. All of the characters’ stories are completely plausible and represent different ways in which the fossil fuel industry harms Americans today.

But making a film with the intention of promoting an idea risks flattening certain dimensions of the world it portrays. The West Texas setting is presented as hostile terrain, an empty expanse of foul chemical odors, ground zero for the destruction of the climate and the earth. The only character from Texas is a tough-looking Southern guy whose family was forcibly removed from land they’ve owned for generations after the government greenlit a pipeline project there. In one scene, he offers a vegan deer meat; in another, his wife tells someone who asks for water that they only have beer.

These moments of apparent comic relief miss an opportunity to more deeply reckon with the South’s role in climate justice, given that so much of the country’s energy resources and petrochemical products are drawn from the region. The depiction of a pair of gun-wielding pipeline workers later in the movie doubles down on the notion that anyone connected to a fossil fuel company is its blind and unscrupulous defender. In fact, the relationship that many Southerners have to the industry is complicated, tied up in identity and health and livelihood. These are the people who have the most to lose when fossil fuels are retired from use. By immediately positioning them as the antagonists, the filmmakers have failed to acknowledge that any just transition away from oil and gas must offer the communities extracting the raw materials something, too.

That the film was envisioned from the outset as a piece of propaganda raises the question of who its intended audience is. At the New York screening, Goldhaber argued that mainstream protest tactics have not been effective in the fight against climate change so far.

“At a certain point you have to ask the question, ‘Do you need to change your tactics to force the system to reform?’” he asked.

The “you” appears to reference individuals in the climate movement who have pursued nonviolent actions, such as mass protest and divestment campaigns, intended to pressure governments and institutions into curbing fossil fuel development. While these measures may have helped galvanize support for climate-friendly policies and mainstream concepts like climate reparations, they have done little to curb the power of the fossil fuel interests that are so often the targets of protesters’ ire.

Today, companies like Exxon Mobil and Shell, emboldened by record-breaking profits following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the resulting energy crisis, are expanding their exploration efforts around the world. Despite the Biden administration’s passage of numerous landmark laws designed to spur investment in the clean energy sector, recently approved megaprojects in Alaska and along the Gulf Coast promise to lock in new fossil fuel infrastructure for the next several decades. These developments come as scientists warn that no new fossil infrastructure can be built if we are to limit global temperature rise to 1.5 degrees Celsius above preindustrial levels and avoid the most disastrous impacts of climate change.

In light of these conditions, How to Blow Up a Pipeline functions as a sort of wakeup call for peaceful activists to consider a different approach. As the book and film have gained popularity, however, law enforcement has taken note. In 2021, an intelligence command center in Texas distributed a memo that linked to an interview with Malm and warned of activists interested in sabotaging fossil fuel infrastructure. A separate center in Kansas City, Missouri, alerted law enforcement to a “developing threat” related to the film earlier this month, according to the Intercept.

For now, it remains to be seen whether the movie will be remembered as a unique entry into the heist genre or a work of propaganda that spurred radical action. What’s undeniable is that Malm’s book and the film adaptation have dusted off an old tool for political change and laid it out for use.

“The task for the climate movement isn’t to wait until it’s extremely late, which it already is, but to move ahead and to use opportunities of extreme climate disaster, which are raining upon us, to drive this point home to people,” Malm told Remnick on the New Yorker’s podcast. “We can’t have more fossil fuel infrastructure and a habitable planet at the same time. We need to choose one or the other.”