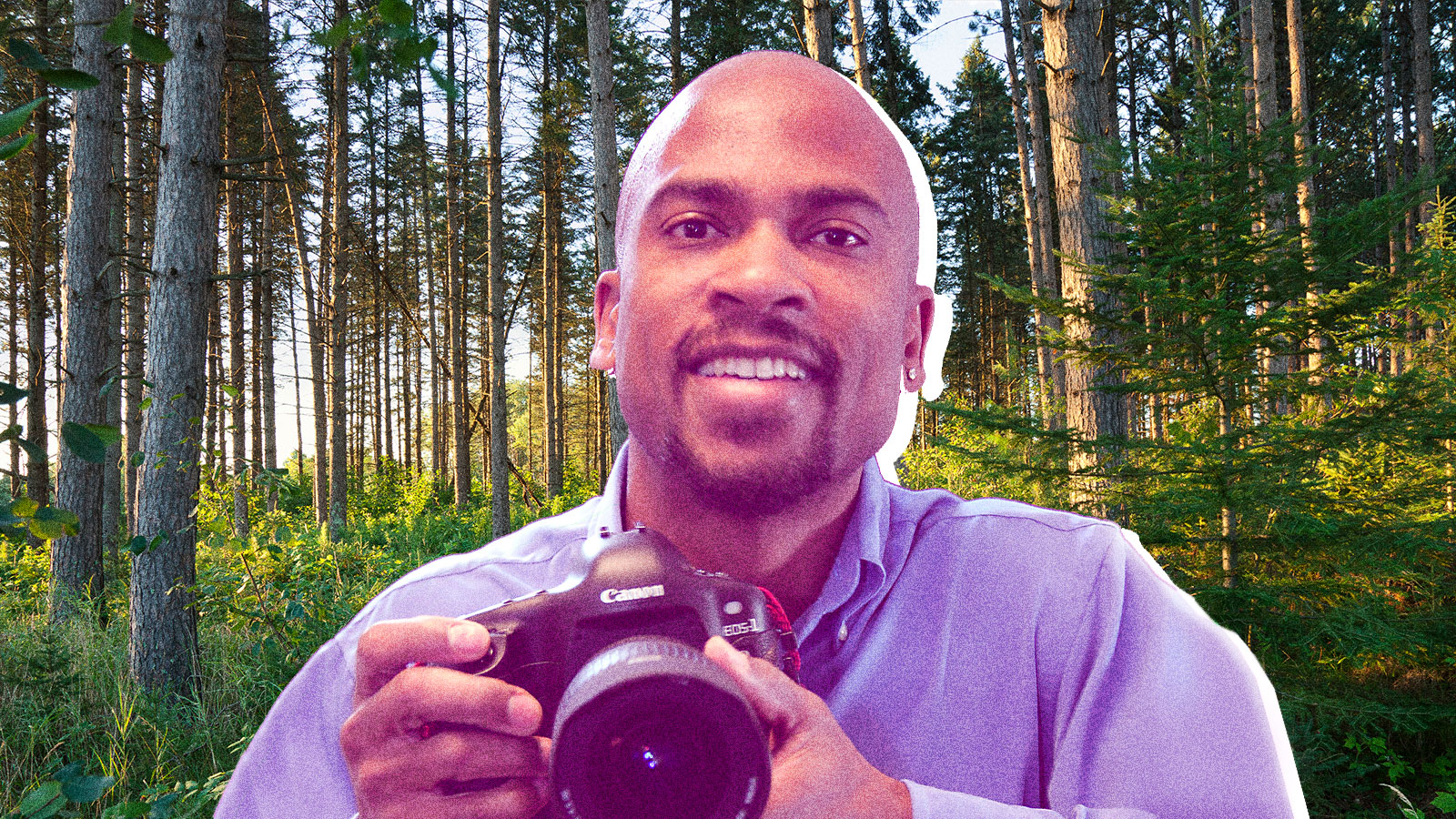

If you’re under the impression that the great outdoors is a bastion of racial harmony, Dudley Edmondson would like to disabuse you of that notion. Edmondson, a longtime wildlife photographer and filmmaker who lives in Duluth, Minnesota, says he gets some, uh, interesting reactions to his outdoor pursuits because he’s black.

While Edmondson was taking pictures of wildflowers in his own neighborhood a few years ago, an elderly white woman came up to him, demanded that he hand over his film, and then called the police, convinced that he was casing houses. “You don’t look like any nature photographer I’ve ever seen,” he remembers her saying.

Weeks later, Edmondson was taking pictures of different species of flowers along the highway, lying down to get close-ups, when a state trooper rolled up and said he had gotten a report of a drunk black man on the ground. The trooper looked a little embarrassed when he learned the real story.

“Unfortunately in America, people still see color first,” said Edmondson. “It’s like, if I would have been a white guy with a beard and a mustache and a pith helmet, and I had all of this gear, you wouldn’t have asked me anything.”

Across the country, police are routinely called to investigate black people doing the most mundane things — waiting for a business meeting in Starbucks, delivering newspapers, and, no joke, golfing too slowly. It happens in parks, too. Last year in Oakland, California, a white woman dubbed “BBQ Becky” called the police on a group of black family and friends who were having a cookout at Lake Merritt, ostensibly for using a charcoal grill. And in Mississippi earlier this year, an elderly white woman pulled a gun on a black family at a KOA because they didn’t have reservations.

But Edmondson is part of a growing group of people who are working to create a more welcoming environment in the outdoors. Their joint efforts, through art, writing, and community building, seek to bring more diversity to parks and public lands, and to the images we see in movies, magazines, and advertisements.

Those images tell us “something about who we think actually has something to offer around new environmental ideas,” said Carolyn Finney, author of Black Faces, White Spaces: Reimagining the Relationship of African Americans to the Great Outdoors. “The majority of the time, what we see are white faces.”

Edmondson got interested in the outdoors as a kid, exploring the woods outside Columbus, Ohio, where he grew up. He has worked with young people to get them interested in birdwatching and hiking, and challenged assumptions about who a “typical” environmentalist is through public speaking, directing a citizen science project, and shooting documentary film projects for The Nature Conservancy.

But as recently as 2000, Edmondson didn’t know any other African Americans who considered themselves outdoorsy. Figuring that they must exist, Edmondson went looking. Starting in 2002, he traveled the country, interviewing and photographing African-American role models who were passionate about the outdoors. Four years later, his quest became a book, Black and Brown Faces in America’s Wild Places.

Elliott Boston III, Mountaineer. Dudley Edmondson

“Frankly, the publisher thought the only people who would be interested in it were brown people who were already outdoors,” he said. So they didn’t put a lot of effort into promoting the book. Edmondson didn’t even do a book tour.

But the book quietly took on a life of its own. Edmondson has heard from young people who read it and were inspired to work in outdoor education and conservation. High school teachers in St. Paul used it as the basis for a pilot course in 2010, and Edmondson said it’s appeared in interpretive centers in some national parks. There’s one young woman in Atlanta “who literally buys copies and gives them away,” he said. Photos from his book most recently appeared in a climate change exhibit at the University of Rhode Island’s Providence Campus Gallery this month.

“Since writing the book, so many people — even in this past week — have told me how important it was to see images of people like themselves outdoors,” Edmondson said.

The book was, to Edmondson’s knowledge, the first to deliberately highlight images of African-American role models in the outdoors community. Today, that approach has taken off. Instagram, in particular, has become a big platform for literally putting people of color into the picture where they haven’t been before.

Ambreen Tariq launched the Instagram account Brown People Camping in 2016 to promote diversity in public lands and the outdoors. The Unlikely Hikers Instagram account, started in the same year by Jenny Bruso, a Grist 50 member, shares photos and stories of people who are typically underrepresented in outdoor lifestyles. Another group, Brown Girls Climb, started by Bethany Lebewitz in 2017, posts images of women of color mountaineering and rock climbing. Combined, these groups have well over 100,000 followers.

Instagram is just one slice of a bigger pie: The next challenge is changing reality. The overarching goal is to turn the outdoors into a space that’s comfortable, safe, and welcoming for everybody — as much as the outdoors can be all of these things, of course. There’s still a ways to go. In 2017, the National Park Service reported that 78 percent of visitors were white and only 7 percent were African American.

The number of organizations promoting diversity in the outdoors has exploded in the past decade. The nonprofit Outdoor Afro, founded by Rue Mapp in 2009, is a development program that helps black leaders around the country hold events that get people outdoors and trains them to work for inclusion in recreation, nature, and conservation.

Yanira Castro, the director of communications at Outdoor Afro, has seen people in the program transform from self-described couch potatoes to, just one year later, hiking Mount Kilimanjaro.

Leaders are required to do monthly events and post the pictures on social media. Over the past 10 years, the organization has collected hundreds of thousands of pictures of black people spending time in nature and “doing everything under the sun,” Castro said.

Those images are now in high demand from corporate partners who are working to change the face of the outdoors. North Face, REI, and Patagonia routinely come to Outdoor Afro and ask to use their database of photos for their advertising campaigns and social media, according to Castro.

“There’s no magic formula to this, but you gotta put the images out there for people to see,” she said.

Lynnea Atlas-Ingebretson, Outdoor Educator, from Black and Brown Faces in America’s Wild Places. Dudley Edmondson

Some brands, including KOA, Marmot, and Merrell, have signed the Outdoor Industry CEO Diversity Pledge, committing to hire and support a diverse workforce and represent underrepresented populations in their marketing and advertising. If the media, nonprofits, and brands become “more inclusive in the story we tell about the outdoors,” said Teresa Baker, the founder of the pledge, the assumption that it’s “unnatural” for black and brown people to be in outdoor spaces will fall by the wayside.

There are signs that the recent flurry of activity around getting people of color outdoors is having an effect. For instance, of the 1.4 million households that were first-time campers last year, 51 percent were non-white, according to a report by Kampgrounds of America. “Camping is the new cultural melting pot of North America,” the report declared.

The outdoors diversity movement has come a long way since Edmondson started his book back in the early 2000s. But he’s also “a teeny bit bugged” when he reaches out to the younger Instagrammers and they don’t respond. “I just would like to be of some service to them, but they just don’t seem to care,” he said. “I’ve been doing this stuff since before they were born!”