It was the year 2028, and I was hiding with eco-terrorists in a cabin deep in the woods. We were trying to avoid detection by the surveillance state, which was tracking activists after attacks on oil and gas infrastructure. Birds were dropping dead from the sky, and a dust storm raged around us, turning the sun crimson.

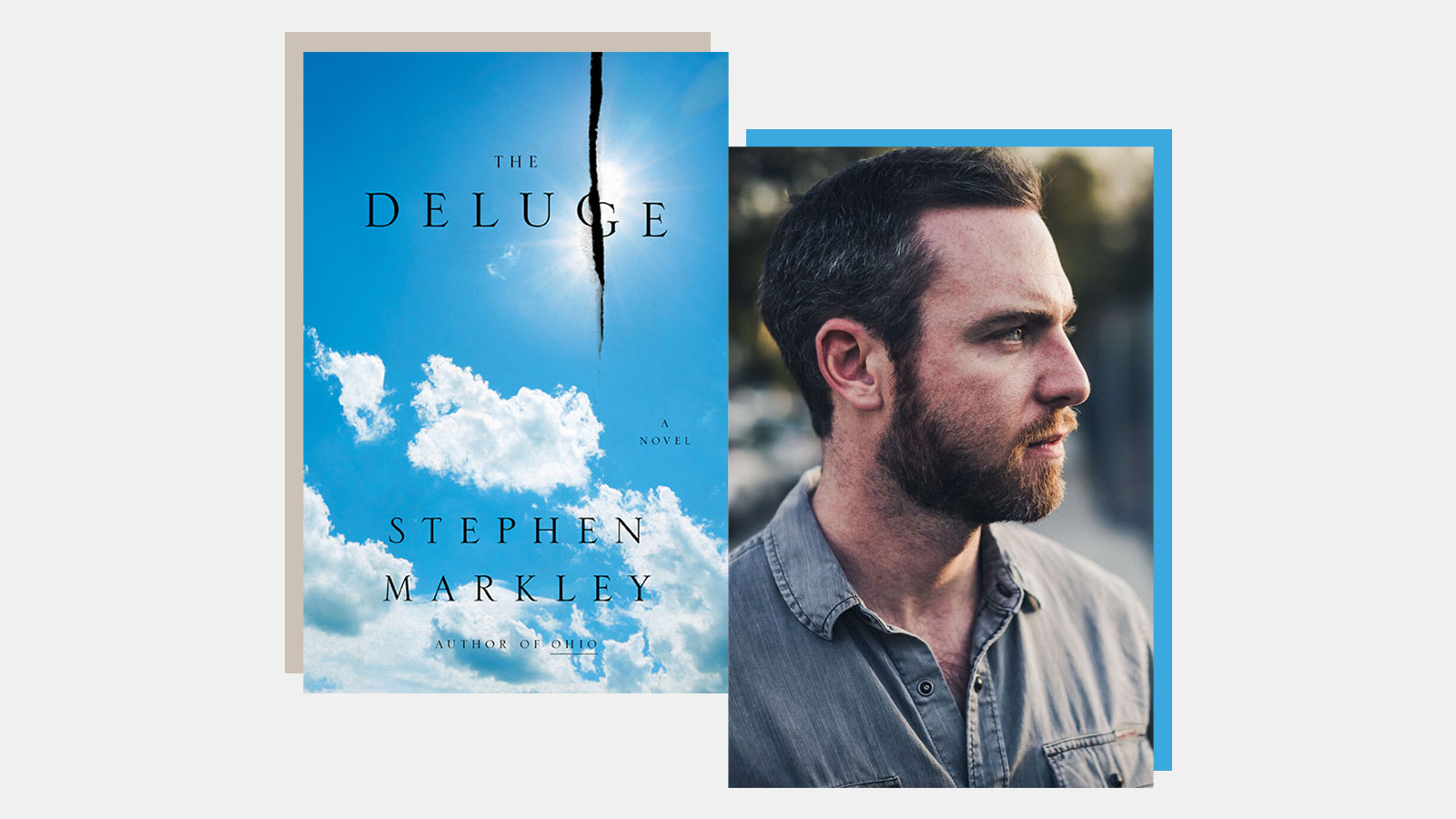

I was relieved to wake up from this dream and shake my paranoia that the FBI was after me. That’s how immersive The Deluge is, an ambitious new novel by Stephen Markley. My subconscious had picked up the storyline around page 200, and after I got out of bed, I couldn’t remember exactly where the book stopped and my dream began. Was getting followed by a police cruiser while driving a van full of explosives part of the plot? What about that night walk through the forest with the conspirators?

Bridging the recent past with a climate-wrecked future, the hyper-realistic novel follows a sprawling cast of characters from 2013 until the 2040s. The Deluge stars both the people trying to save the world and the ones wrecking it: a scientist, an advertising strategist, a math genius, a drug addict, politicians, activists, and right-wing authoritarians. Over the course of nearly 900 pages, climate disasters get personal, with roaring fires and ferocious floods coming for the characters’ loved ones. And the brutal weather brings a violent reaction with it. By extrapolating from present trends, Markley conjures a future filled with even more extreme far-right zealots, savvy fossil fuel PR campaigns, and laws cracking down on protesters as terrorists.

Markley’s dark debut novel, Ohio, also took on a big social subject — the opioid crisis — but focused on one single night in a working-class town. The Deluge, by contrast, spans continents and careens through decades’ worth of nightmarish scenes that feel like they were made for Hollywood. (Markley has also written storylines for the Hulu comedy Only Murders in the Building.) Stephen King, who read an advance copy of The Deluge, called it “the best novel” he read last year. That a horror novelist loved it tells you something.

It’s rare to find a book that captures the complexity of the climate crisis, from the real-life scientific projections to the social and political trends, especially one that’s compellingly readable. I called Markley to learn more about how he accomplished it. This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Q. Let’s talk about the challenges of turning climate change into really good art. It often feels like a book or movie is trying too hard to inspire people to change their behavior, and that attempt is almost distracting from the story. How did you deal with that?

A. I identified a bunch of traps with writing about any big social subject matter. Unfortunately, telling the reader what they should believe is always a pretty surefire way to make a bad piece of art. So even though I have, especially after all this time, very, very strong opinions about the climate crisis, I was never using a character as my mouthpiece, but rather looking at a variety of opinions and ideas and trying to decide, “What would the human being I’m creating actually think about this?”

And in doing that, you have main characters who all want to do something about the climate crisis, but are really annoyed with each other, or actively despise each other. Because, much like in the real world, everybody thinks they’re right about everything. It’s getting at that real feeling when you’re in the midst of a crisis, how human beings can splinter and decide, “No, I am right, this faction is correct. We have to do it this way” — that sort of polarizing atmosphere.

Q. Do you think that the polarization around climate change could be fixed?

A. Well, right now, no, absolutely not. There are people who are so ideologically committed to not doing something about this, there’s barely any point in trying to change their minds. Having said that, I do think that as we change the industries, the politics will begin to change. You know, I think that was one of the smartest elements of the Inflation Reduction Act — scatter your investments in every single congressional district and basically make it politically impossible to dislodge.

One of books that I really admired was Leah Stokes’ Short Circuiting Policy, and the way in which clean energy laws in different states have produced really different effects on Republican legislatures in those states. In Iowa, where wind has become an enormous political force, people have a different set of ideas about clean energy than in Ohio, my home state, where it’s just been so much more difficult. Part of the challenge that lies ahead is changing the industries quickly enough to change the politics on the ground. I do think once people’s livelihoods are invested in decarbonization, we will see a shift.

Q. I’m from Indiana, so it was cool to see that so much of the book was set in the Midwest.

A. Yeah, it’s obviously partly because I’m from the Midwest. To me, it was important to have characters who don’t believe in the climate crisis or don’t care about it, and to see them on the ground living lives that I think a lot of people can recognize.

Q. I liked how your book portrayed the PR messaging coming from fossil fuel companies — one of the characters helps the oil industry create a giant greenwashing campaign. Where did you get that idea?

A. It seems so cartoonishly evil, right? But people go to work every day in these jobs, and they decide how to deny, delay, and stall action on climate. You know, I’ve talked to a lot of those people. I asked them for interviews on background and promised not to reveal their names. I thought it was one of the most fascinating elements of my work on the book, because you sit down, or you have a phone conversation, and it’s just like, everybody’s a human being. Everybody’s talking about their kids and their job and what they do on the weekends. And I took that and put it into characters in the book.

You know, I find that a fascinating piece of the puzzle, because people like us who work on climate are filled with dread about it more or less all the time. It’s like, “How can we not be moving faster on this?” It is really mystifying. And so demystifying it was something that was important to me personally. But it also lent the book a very realistic vantage point.

Q. Speaking of realism, we’ve been seeing disasters that keep outpacing what climate models thought was possible, like the heatwave in the Pacific Northwest a couple of years ago. How did you decide what kinds of events were scientifically plausible?

A. My thinking was, let’s go to the absolute outer edge of what’s possible, first of all, to create a good Hollywood scene, but second of all, because just in case one of them happens … I know that sounds nuts. But let’s take the Pacific Northwest heat wave. When that happened, I was editing the book, and suddenly I’m looking at all my temperature numbers — like, “Oh, this was a record temperature in London at this date, and this is a record temperature in D.C. at this date” — and the numbers in the book all looked so silly because of this insane heat that engulfed several provinces and a few states. It was just totally jaw-dropping.

I wanted to have the meteorological events in the novel be outside of anything we’ve experienced yet so they couldn’t be usurped. And there are a couple of big ones that are definitely on the outside fringes of what is possible. I was living in L.A., and I woke up at night, and everybody in the county got a text like, “Just in case this wildfire destroys the city, prepare to evacuate.” Well, that was terrifying. And that text message became a major chapter in the novel.

Q. A few years ago, it felt like climate fiction was a pretty niche subject. Do you think that’s changing?

A. One of the things that bothers me about climate fiction — I don’t want to disparage any author, because it’s really hard to write a novel — but none of it laid out the real choices we have to make or talked about the carbon lobby as an actual force in our society. I’m painting with a really broad brush — I’m sure there are stories that do this. But let’s look at the actual problem, and every single issue that stems from it, and what to do about it. And when you get into the nitty-gritty, that was a novel I wanted to write. So nothing allegorical, just straight to the eye — what is the situation we’re in and what do we do about it?