There’s no longer any need to ask if heat waves are influenced by climate change.

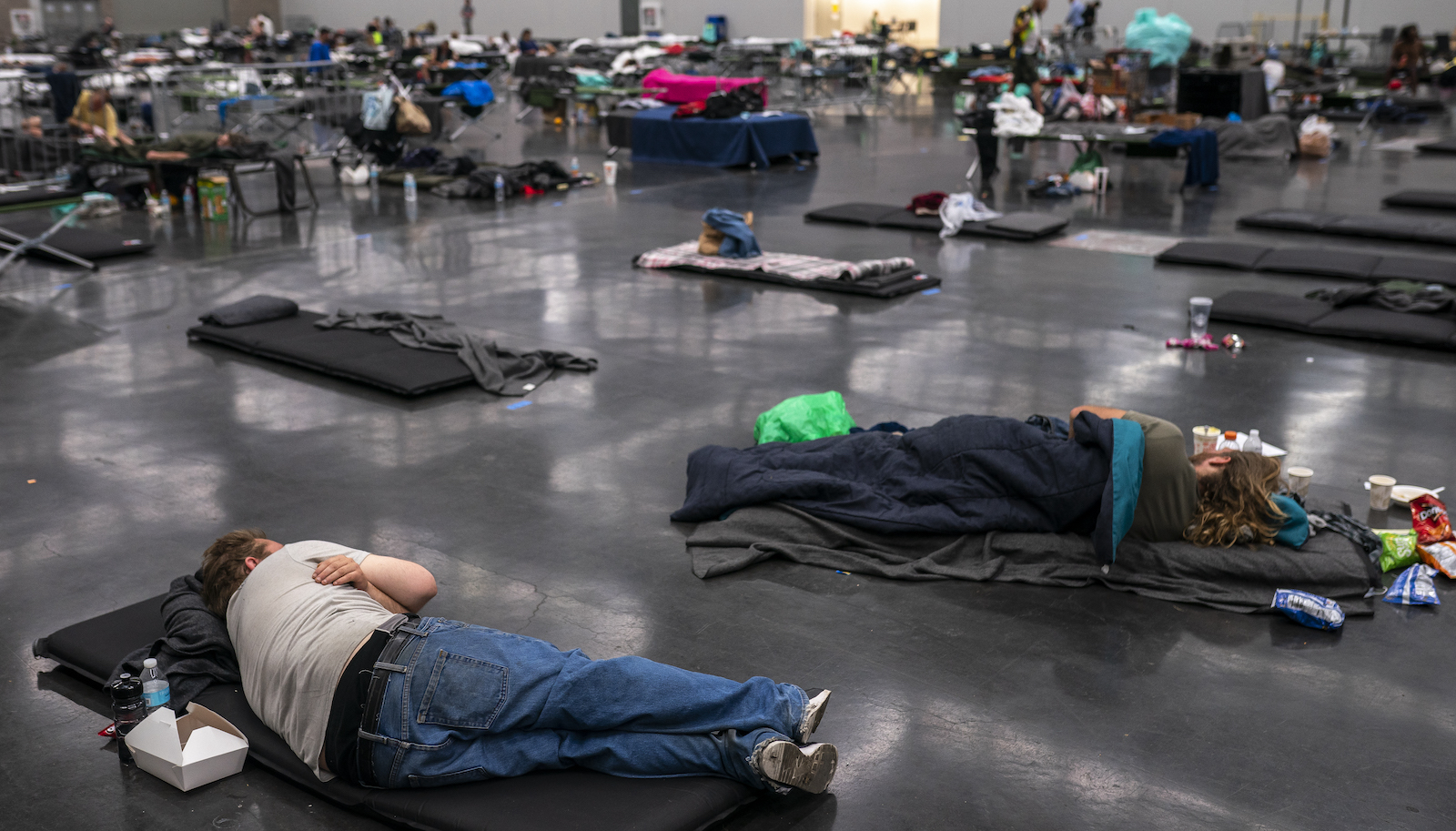

On Monday, temperatures in Washington and Oregon soared to well over 100 degrees Fahrenheit, crushing records and leaving locals — many of whom don’t have air conditioning — struggling to find shelter from the suffocating heat. In Seattle, fans and air conditioning units were sold out at major retailers as temperatures reached an all-time high of 106 degrees Fahrenheit, marking an unprecedented third straight day of 100-degree heat. In Portland, light rail cables literally melted amid record-smashing temperatures up to 40 degrees Fahrenheit above normal.

And some scientists are beginning to say that not only is the once-in-a-millennium heat wave broiling the Pacific Northwest linked to climate change — but that it’s safe to assume that all heat waves are being made more severe or more likely as a result of all the carbon emissions pumped into the atmosphere.

“Now, if we have an extreme heat wave, the null hypothesis is, ‘Climate change is making that worse,’” said Andrew Dessler, a professor of atmospheric sciences at Texas A&M University. Instead of having to prove that climate change did affect a heat wave, Dessler explained, the burden of proof is now on any scientist to prove that global warming didn’t play a role.

That’s a far cry from two decades ago, when scientists hesitated to link extreme weather events to climate change at all. When researchers did connect an extreme flood, drought, or heat wave to human-caused warming, their research was often released years later, due to the long process of peer review. But now, as heat extremes (and research) continue to pile up, scientists have grown increasingly confident that climate change plays a role in essentially every one of them.

“Every heat wave occurring today is made more likely and more intense by human-induced climate change,” tweeted Friederike Otto, a climate scientist and the associate director of the Environmental Change Institute at the University of Oxford.

Over the last decade, researchers have analyzed over 100 heat waves around the world, concluding that climate change made almost all of them more likely or more severe. (In a few studies, the results were inconclusive.) One study found that the 2017 European heat wave nicknamed “Lucifer” was made four times more likely; another found that an exceptionally warm summer in Texas in 2011 was made 10 times more likely.

In a few cases, researchers have calculated that heat waves would have been virtually impossible without the 2 degrees F (1.2 degrees Celsius) that the planet has already warmed since pre-industrial times. Scientists estimated a heat wave in Siberia last year — which brought temperatures in the Arctic circle to 100.4 degrees F — was made 600 times more likely due to the warming climate.

“The analogy that people often use is loading the dice — you have dice and they used to be fair but now we’re loading up the sixes,” Dessler said. “But what’s actually happening is we’re hitting the point where we’ve added another side. Now we’re rolling sevens.”

Many areas of the U.S. simply aren’t prepared for that kind of extreme heat. According to the U.S. Global Change Research Program, major U.S. cities experienced two heat waves a year in the 1960s; now it’s more like six. The heat wave season is also 47 days longer — which helps explain why the Pacific Northwest is getting hit by extreme heat as early as June.

For Dessler, the scary thing is that all of this is occurring at only 2 degrees F (1.2 degrees C) of warming, and the planet is slated for around 5.4 degrees Fahrenheit (3 degrees C) of warming before the end of the century. And climate change, he pointed out, doesn’t proceed linearly. Things might seem gradual until all hell breaks loose. “It’s going to be a lot worse than three times as bad,” he said.